Claudia Böse in conversation with Matthew Krishanu

Matthew Krishanu: Claudia, I guess the first thing is why ‘idiom two’? What does it mean in relation to the paintings?

Claudia Böse: Yes. It is quite a complex word ‘idiom’. I wrote down a nice definition for myself to read out to you and then take it from there.

(reading out) For me “idiom is a natural manner of speaking to a native speaker of a language.”

Me being German I feel now I can use idioms like a native speaker in this country, on one level. But I also feel as a painter I think my work is also full of idioms which can be read by other painters, and I think also English painters rather than German painters. I feel there is something about the language I use which has become quite native to painting and to England. Some people have said to me ‘oh you are more English than the English are’. So I feel that’s why it’s called ‘idiom’.

It’s called ‘idiom two’ because I just had a much bigger solo show in Suffolk, my first solo show in Suffolk, in January, and that was called just ‘idiom’. This show ‘idiom’, was selected – the way the work has been juxtaposed with each other – was selected by other artists, ten painters, who I respect very much. So that took a big weight off my shoulders. We all met in a community hall in Ipswich, and I brought along 60 paintings and said ‘please you sort it out’. I put paper on the floor and said this is the space we need to sort out… four clusters of work they had to sort out. They did an amazing job because when I then hung the work in Halesworth at The Cut it worked beautifully. I took the work out of the bags and just hung it and it worked.

So this show is called idiom two, number two. But also, I think I’m quite interested in language, so it is also idiom two, too.

MK: That’s really nice because I guess the first thing I thought about when you said idiom

is the native speaker, a native way of speaking – it’s very much ‘painter to painter’. I think the whole programme is about that: how painting communicates. You mention that you think of your work as more English – more British – than German. I was wondering if you can talk more about that. You know there is that book ‘The Englishness of English art’ by Nikolaus Pevsner. I was wondering if you could try and verbalise what qualities you think make them look British. I think that’s very interesting for abstract work.

CB: It’s a really good question. It is very difficult to answer this question.

MK: Yes – which is why it is idiomatic – it’s ‘painter to painter’.

CB: I feel it’s the way I am framing within my painting. That makes them British. I frame them, very much influenced by pop art. If you look at it – each work is framed in its own way. If it was German it would be just the surface. It would just be one surface, one aspect of my painting but not the other. It is the framed-ness, the containment.

MK: Yes – it reminds me of Howard Hodgkin, how he’ll have edges round curtains, or windows…

Audience: They are also small, very personal, and conservative with a small c.

They’re not big and brash – like de Kooning or Pollock.

CB: Yes, it is interesting because, yes they are domestic. There is something about the domestic because they could be table mats, they could be screens. My work is also about things you handle every day. It’s not so explicit in this show but I’ve used the format of CDs, cassettes, of screens, of steps … but not very consciously. If I think about Gerhard Richter, Polke or Kiefer… making really big work, big bodies of work, which I feel as a German, is complicated to work with these big formats.

MK: It’s interesting because when you mention framing, immediately I thought of the miniatures [Christian icons in the space], and when I came in – particularly the one with the brown frame and those light patches in [pointing to the painting ‘Helle Brocken’] – I was making connections, visual connections, between the miniatures which are often similar scale but are also like little windows, little frames. I was wondering how showing in this space has affected the work for you, both in the Christian overtones, and then all this other visual information around?

CB: When Robert first told me about this space I booked a train ticket to London to check out the space to see if I could see my work in it. As soon as I walked in I could see my work living, sitting on these walls here, next to these icons. Icons on one level are ideological vessels, they carry quite a lot of weight with them, and it might not be quite the vessels I subscribe to but I feel mine are also ideological vessels too. So I think they feel at home here. Much better than in a white gallery space where there are catalogues on the side, flashy postcards and high-heeled assistants. I feel they sit much better here because although money is involved here too and that sort of thing, I feel, I have been successfully – and unsuccessfully – kept away from the money world with my artwork. I thought recently quite a lot about his. Why have I not – the colleges I have been to, the people I have met – why the hell haven’t I got a gallery that sells my work every two years, regularly? It has got to do with the money. I don’t want work, art – now especially – when you think about the off shore tax evasion and all that sort of thing – I think I don’t want my paintings to be bought by dirty money. Thinking about the private views I have experienced I could never get on with the bankers and the investors… at the Academy Schools, at St Martin’s I always hung around with my fellow students. All along I have been like this without being conscious about it. This interview made me think about this. I have always been looking for a place which, or a gallerist, somebody who understands where I am coming form, who likes that sort of thing, and wants to show work of this nature. There are just very few galleries around who have this as their ideological vessel as a gallery.

MK: No – I mean a gallery would shoot itself in the foot if it didn’t want the money, or if it worried about where the money was coming from – it’s true. And yes, I felt that – it’s quite a humble space, which I like, in here. It’s not ostentatious and yet it is beautiful.

CB: I also like the counselling centre, GP surgery, chiropodist on the way in. It suits me because my work is quite physical and to have that as a way in…as signposted … you arrive already prepared rather than passing Prada and Gucci to this place.

MK: What’s nice as well is you just see people walk through to the Crypt and often pause and look at the work. If you are coming here for that, to get away from the beat, the chaos outside, then it’s a very quiet space.

I was wondering also how you feel about the light in this space? For me, I felt really refreshed when I came here because your work is luminous – it’s full of light. I wonder when you have shown in places with daylight compared to artificial light, how that affects the work?

CB: It affects it a lot, because normally I only show in places where there is daylight, because my work is painted in daylight as well, and it’s really important to me to paint in daylight. But, when I came here, this is the first space ever I went to where it was not daylight and I felt it’s okay. The environment here helps. It might take things away but it adds things…it balances it…with what my intentions are. The light is not so important any more. I learned this when I put the work up here. This is very interesting.

MK: I felt similarly – almost any other space that was underground, with heavy arches and things, I would think ‘no that wouldn’t be great’. But I agree, I think partly because of the stillness of this space, it seems to lend itself to painting, especially ones that shine like yours. And just a visual sweep around, you see the icons, you see your paintings… and you’ve got a whole cluster of postcards on the wall as well, and often of the same paintings as you’ve got on the walls. Can you say something about how that works in relation to the actual works?

CB: That set of postcards I thought of once I hung my work. By the way I had also help hanging from other painters for this show. I arrived here with a set of clusters for each wall but when I got here and hung it, it really didn’t work. But it is so good to turn up with something definite in your mind and then you have to react against it. Because this space is quite different to a normal white space, so I really had to make adjustments. I’m really pleased, because I learnt so much about how I tick by just readjusting it.

On my way home after I hung this work I thought one of the walls is a bit awkward, I didn’t put any work on this wall, there is the water cooler here, a table and a bin. I then thought about what else is important in my work is the real and the reproduced image. The picture of the painting, or the photograph of a painting, and the real thing. I put the postcards on my floor where I live and took a quick photograph of the layout and thought I might take them along and put them on this wall to show what the photograph of the work looks like and there are some of them for show in real in here… to see what the difference is. In my previous two shows I had very good photos of work in life size mounted on mdf board (like this painting is) and just sneaked them into another show, not saying that this is not real, just to see if there is a response. And I did at the Private View, there were one or two people who said ‘I don’t mind it’, ‘I quite like it photographed like this’. It was very interesting for me to think about this. I will continue with this exploration. This is just one element, the real, the fake or the real and the reproduced. There is some educational streak in me which says ‘listen to the real stuff’. My work reproduces quite badly on one level on websites because the way it is taken digitally and also reproduced on the computer; you’ve got the light coming from the computer which adds that light. I want to do the light! I don’t want the computer to do the light. I feel it sort of doubles it, it becomes a new painting. Quite an interesting painting to look at on a postcard but not what it is really about. How flat it just becomes. It’s different altogether. The photographs are taken by a photographer who takes photos of John Hoyland’s work. You also can’t capture matt-ness and shininess.

Audience: I’ve only seen your work on postcards for years and years…and this is so different. A lot of it is the texture.

MK: There is that uniformity of surface in postcards, which is a problem, and also because they are light printed on a piece of paper rather than stuff built up, there is no real physicality to them. I think that’s the first thing I felt when I looked around is how you really look at the edges of the canvas as well, the fact that some of them are on wood, some of them canvas, and you can see the paint splashed on the edges as well. And others are on paper, mounted on board. I am just wondering as a painter, how this affects how you paint, whether you are working on paper, board or canvas. How does that influence what you get or actually how you paint?

CB: I choose intuitively a surface when I work, I choose different surfaces and then suddenly I end up just with paper or just working on boards. I always work on about 10 paintings at any time so I gravitate towards hard surfaces, or floppy surfaces. Hard surfaces is paper – because I can just stick the paper on the wall, and it is hard as well. There is this thing – the floppy painters and the hard surface painters. When I am in a cave painting phase I use wood (MDF boards) or paper and when I want something a bit more poetic then I use canvas or linen. Sometimes I decide to stick the floppy surface on a hard surface, or the other way round. I don’t know what you do, I’ve only seen canvases of yours.

MK: There are a couple of works on board, and I found the paint dries differently on board from on canvas as well, because it’s less absorbent. And something like that green one on canvas [pointing to the painting ‘Keep the wound wide open’] you can see textures in it as well, you can see a history under there. It’s almost as if with canvas I feel you almost expect there to be layers beneath whereas with board – for instance that one with the turquoise round the brown, it feels very much… very complete, like it’s just dropped whole. I was wondering if you want to talk a bit about layering in your work and how important the history, the visible history of the paint marks is for you.

CB: So, the green one you have chosen, the title is called ‘Keep the wound wide open’. It’s interesting, because it is about skin and the body in comparison to the other green one which is called ‘Formation’ (and I like the German word ‘Bildung’ for this one). The ‘Bildung’, the ‘Formation’ is more like an ice rink, although it’s on a chalky surface, it’s not too clean in that way. But the green one [‘Keep the wound wide open’] it also coincides, because apart from the reading – there’s a whole selection of texts that I’ve selected for this show and the previous show of things that influence me while I am painting …I just copied the pages of the books I read. I can’t choose everything that I read of course.

For the last year I have been reading a lot about Russia, Russian history, especially in the Second World War, and the German one, and I feel – previously I read Polish history, but I feel reading about the Russian history I know why it took me nearly 30 years to get down to reading about Russian history. Just the horrendousness of all the exchanges – left, right and centre. So, quite a lot of paintings have that wound, have that sort of openness about this, or closing-ness. Another painting in that series is called ‘Don’t fire somebody shouted’. It’s quite abstract – ‘Don’t fire somebody shouted’ but I think it gives the viewer not much option of what to think about the way to look at the work. Recently I started to get much more explicit about my titles for works – or diagnosis of a work maybe – to give a way in a bit more. So, talking about surfaces – this painting here is much more on the surface, it’s more superficial. I called it ‘Idiom’ – it changes, and it’s reflective. And idioms become reflective of where we live, the culture where we live, it changes, it’s quite fluid.

MK: It’s almost like glass, or in the small ones, with the very oily… you’ve obviously used a lot of oil in them – and that sheen.

CB: That little one called (pointing to) ‘Privilege’ next to (pointing to) the ugly one which is called ‘The length of daylight’.

MK: Yes, It’s very interesting to hear the words like ugly … or the wound… and obviously the historical topics you are talking about are also quite laden with trauma, and the trauma of memory.

I found that came very strongly across in the IDIOM TWO TEXTS which are very interesting snapshots both into your practice but also into the book [they come from] because they sort of stop mid-sentence as well. I think that’s rather nice as well, because often people have KINDLEs these days or read online and the idea of a book page being almost like a fragment. But each of the fragments is very deep, quite heavy material, particularly the last one the Valerie Sinason: ‘Mental Handicap and the Human Condition’. It really takes you right into a centre with people with profound learning disabilities, and self-harming and the pain of that, and others which look at particularly Freud’s texts on trauma and so on. And yet when you come in here you see peace, and you see light and you see almost a sense of healing I think is a word I would use. I was wondering if that bothers you that that’s a reading of the work or how you lay the thinking behind the paintings in relation to how they are read.

CB: I wonder if it is a good idea to quote a bit from her text, her text is the last text in my compilation. ‘Mental Handicap and the Human Condition’, the second line (reading aloud) ‘it is not surprising that some workers defend themselves against the pain’. She is talking about social workers [carers]. I feel my work might almost – can be described as a defence against pain but in order to defend pain you have to be really engaged with it, you have to know what you are defending, to be really successful in defending it, in creating a peaceful thing at the end, I sort of turned it round and used the mess and the chaos, and perhaps not the normal way of being … I arrive at this. The other words I can think of is from Valerie’s text is the weight of meaning behind every gesture every human being makes whether we are normal or not normal. I was very impressed when I read her book because it is about severely handicapped clients she has got, and she’s a psychoanalyst who just works with this client group. So if they just dribble when she’s saying something, or lift their arm … or just say ‘ooahh’ … she listens to this. And she says, ‘why has this come at this moment, right now?’, or ‘why is this girl coming half naked in?’, and she says ‘oh you just wanted me to see you’ . This girl then dresses herself normally then. She got it. And I feel because I am very interested in all of this… sorry, I got lost now, I’m so interested I got lost!

Audience: Would you accept that perhaps these paintings are presenting symptoms as it were? That we as an audience would kind of attend to in the same way, or not?

CB: You know, I would hope so. I think so. I hope you recognise it, and you can see, I can see – this needs to be taken care of. There is something precious. It’s not just a picture about something. Of course I like pictures but there is something else going on. Yes, taking care of. The other wording in the text where Valerie Sinason says I think I want to ‘break through this conspiracy to silence’. I really like to call the thing a thing really, it’s a fart or whatever … or some leakage or something… I feel we are conspiring a bit too much to keep quiet about this. I feel that’s where I am coming from, what also interests me in the selected writers.

MK: Yes, you saying that makes me realise that all these extracts are about the non-verbal, how this is materialised in some way, whether it is the physical actions of the people with the profound learning disabilities or the trauma of history, how that re-shows itself, but doesn’t get spoken about. Which makes it interesting as well that it is called idiom – because that’s a verbal, normally a verbal idea – whereas these are non-verbal paintings.

CB: I also chose a text by Jose Saramago, a Portuguese writer, his text ‘the old and the young’. Because I am the sort of age now, where I really have to think where am I – I am getting older – where am I sitting in all this? He writes about the old and the young but actually addresses cynicism in this piece of text. How cynical we are and that we don’t look after life very well sometimes. He writes about the boatpeople arriving in Spain and Italy…and just as soon as he’d written about old and young – for example what do we do – these guys got lost half way coming from Africa – was it three years ago on that 11th November in the news, 10 people got drowned coming across in a dingy from Africa. And our concerns about wrinkles! That’s the old and the young.

MK: I think about communication in these as well. Whether humans – like with cynicism – how people communicate, and what they don’t talk about. I was wondering with your painting how the process works? Do you start with sketches? Do you have an idea of what you are going to paint when you begin?

CB: No.

MK: So it’s completely just the surface and paints?

CB: Because I know how good I am at pretending, thinking I know what I know, thinking I know what I think, or know what I feel. I think only through the process – because my work is process led of course – I only then find out what’s what. And most of the time I arrive at the same thing again whether I like it or not.

MK: And are they over a series of days, do you wait for layers to dry before you paint on the next or is it in one sitting usually?

CB: It varies. Some need to be short, others need six months, others I know the next day that it’s finished, others I know straight away it’s finished…there is no easy answer to it. And sometimes – like now – as part of this show, looking at also my older work on the internet, I feel I could go back to this painting I think, and I think no, I’m not going to work into this, I’ll just leave it. It’s also what kind of paints are just knocking about. I leave chance a space, accidents a space. But I think I’ve painted long enough to know that I don’t do accidents anymore, and chance too much. I orchestrate the situation.

MK: And, hearing you talk about finishing work… can you articulate what it feels like, when… how do you know that you have finished a work? And can you articulate how that is discovered because you don’t know obviously when you start what you want to achieve?

CB: It resonates with something, there’s some affiliation I feel, something that I wanted to mention or to address feels contained at that moment. But sometimes I don’t know it straight away…I need to come back to the studio three days later, or even six months later, I have it turned round, and then I feel ‘ah yes, it is finished’. It’s also just very practical, you feel there is nothing else you can do. You said everything you wanted to have said. It’s like – I also feel this is a bit like an equation – I feel equation done: I have done it – equals that.

MK: And the title comes after the works?

CB: Yes. There is some title floating around while I read something but then it has its own evolution. I also I feel I am just starting to think about the title because of course being a mainly visual person, I haven’t trusted language or my own capabilities with language as well as I do with painting. But I feel now I am getting more into a dialogue with an audience and my titles. It’s very interesting the ones I feel when the titles are spot on for me because these paintings have gone. I feel obviously there is something. I have given it really a name. Where – perhaps – where it resonates with most people basically. There is something there where it resonates. Some titles they change after two or three years as well or six months. I think, hang on, I need to sharpen this a bit, this could be better. Because this one (pointing to a painting) used to be called ‘five blue things’. I thought well this is not five blue things. This is a bit more than five blue things.

MK: And what is it now?

CB: ‘Make me the one’.

MK: Lovely.

CB: ‘Make me the one’. This is much more about anxiety and helplessness and wanting to be wanted, or being picked… than five blue things. But that’s how it works. I said, oh yeah, it’s cool – I need to get this out more in my work, being more specific.

MK: And with that change of title it is almost courageous or more raw, the second title, there is something that holds back in the first one, and the other one is perhaps more generous.

CB: Yes, I feel more generous. I feel I’d better spill it out. I know what they are about. Life is too short now to beat around the bush. You need to have confidence to do this.

MK: Well that interfaces with the audience. Any questions for Claudia?

Audience: Gerhard Richter in a recent film talks about how a painting will hold itself, […]

Do you feel like that, people coming to your work saying it holds itself, it works and you have a kind of sense ‘I want to negate that’ or do you find that‘s fine? Do you work like that?

CB: No, if somebody says ‘it works’ I feel I found somebody who can relate to it, can take care of it, attend to it. […] Because for so long I fought against it. I arrived at something and I can’t do any better than that. I am glad if one person likes it or can connect to it. But I do fight. There are other rules. I have got the rules more in the manufacturing of the work…like ‘it must not be too easy. It can’t come too quickly – these sorts of rules.

Audience: So where do the rules come from?

CB: This is a really good subject for artists, isn’t it? Where do these rules come from?

It’s really good when my mother likes it.

Audience: It’s often somebody.

MK: Your question to me in the comment book when you saw my show was ‘I wonder what your parents think?’ Because it was about my parents admittedly, but that’s interesting.

Audience: A very strong moral dimension then you are working with? Your mother is on your shoulder. You are saying, it mustn’t be too easy…it’s really interesting.

MK: Absolutely.

CB: It’s a good conversation to have with painters because we all have our strong moral codes. With my mother it was interesting to give you an example. I saw the Courbet painting ‘The origin of the world’ and I focused for two years just on this composition of this area of the body. When I was at art school many of the teachers were in their eighties … they said ok, it’s a lovely forest clearing or I can see an angel descending from sky – anything but! (laughter)

So it is this silence again, a different silence, not about pain, it’s about other things. Back to my mother…I gave a slide show in the town where I grew up in Germany, showing this very body of work. At the end of this show my mother said ‘Claudia this was a really nice show but what is it about?’ I said ‘Mother!’. Then somebody in the audience said ‘Sibylle don’t you know what your daughter is painting?’ (laughter) I said, ‘Mother, I partly painted this because of you, you jump from your navel to your knee caps.’ That’s why I have engaged with this. It’s not me. That’s not what this work is about, just to bring it out. The things that haven’t been mentioned…So Matthew…parents, it is interesting because I did wonder what your parents were doing, because your parents were missionaries. Did they come to your show and what did they say?

MK: They appreciated the show more than anybody else because they had insider knowledge; I guess that’s more literally, autobiographical. I wouldn’t say your work was autobiographical but it’s clearly very close to you.

Audience: When I saw your work online, I’ve only seen it online before and this is the first time here I’ve seen your work, my first response was that they (referring to the paintings in the show) are very much in modernist genre. You gave them very modernist titles, minimal titles, and yet here the titles you are giving them absolutely undermine that notion of abstraction, that particular kind of abstraction. I just wonder … historically you kind of visually are positioned in that area, in a sense and yet they are not somehow because of the way you are talking about them. There are other things about them too, seeing them in the flesh.

CB: I love…loved…modernism but as I got older I thought ‘oh how dangerous’ this clean art, clean spaces, no cobwebs, no dust. Corbusier, I love his architecture, I’d love to buy one of his houses. It’s interesting, on one level I really like this but having thought about the Nazis, they grabbed, they made, they paved the way, this cleanliness, sterile-ness…on one level. But my work comes from ‘hemming in’. If you know my previous work, my figurative work many years ago. If you really focus into my figurative work that’s what you see too. I think I’ve really gone microscopic into my figuration which was [for example] about living, life in Golders Green as a German with the Jews; food; about cars; about plants. I like to be quite tidy, clean and clear but in that sense I feel they are not (modernist, however) I can see that they fit in there.

Audience: Yes, they could, they could. That’s the first obvious interpretation. When you look at them in the flesh, look at them closely, and then they are not of that area at all.

CB: Don’t you think that’s why it’s more important for me to think about language?

Audience: Yes, that’s right. And I don’t think nowadays we can ignore that. And the fact that you have given them these titles, in fact what you are doing, it seems to me, you are engaging with your audience, you are asking your audience to contribute something to the meaning. It’s not finished like in the modernist movement, take it or leave it: It’s a purely perceptual thing, you don’t understand it, you don’t have the language. Again, with your titles you are inviting an audience to interpret, behind the layers. It’s a different viewing process you are inviting which is very much of today. It’s passed through the minimal abstraction.

CB: I do like the modernist paintings as well. Something really pleasant about them. But I really like poetry as well. I wish I was a poet or a film maker. A poet.

Audience: I think they are really poetic.

Audience: I see Rothko… influence and spirituality in sense of the abstraction…Russia and art…Supremacists

CB: I like that work very much, Ad Reinhardt … I like that whole school. I like that they are taking a position and it helps me to take my position within painting and be more articulate about it. All we have got is ourselves, our lives, to really support the work.

Audience: One thing that it does share is the preoccupation with the medium, with the paints, to see what paint can do, what no other medium can do. I like the way you talk about the ground, you use different grounds. We forget it is the interaction with the ground and the paint, isn’t it? We often forget the grounds. I do anyway. It’s tempting to just grab another canvas.

CB: Yes, it’s about handling paint itself. I’d like to be a documentary film maker…but painting…I like the challenge that it’s been done for 500 years and to just take it into the 21st century. I am not going to change the formal: not round, triangular, I want to stay with the same. What can we do, it’s been done for so long. But it’s the handling of things, food, clothes…

Audience: Basic stuff?

CB: Of course. Heidegger wrote a lot about it, the importance of tools. I have no fancy ideas; the paint will tell me what I have to do. At this time and age it’s a bit complicated to be in love with this sort of thing. Should I not be doing some more meaningful work?

Audience: Again, the should I?

CB: Yes, when I read Valerie Sinason’s book … I must say I thought … I should …

Audience: We all think that. Why am I doing this when there are so many other things going on in life?

CB: To make somebody feel listened to…heard…

Audience: Do you think it’s a responsibility for the artist to give something back?

CB: Perhaps be more generous, yes, to share your helplessness, which takes me to Adam Phillips’s text in this show. It’s not very sexy to be helpless, to share sexiness though, that’s very cultural. But to have a certain helplessness, that you’ve just come to your limits what you can do, what you can contribute. Be generous and spill it out what you do, what it is about. Take it or leave it. The more generous I am the more ready I am to cope with it and the feedback.

MK: And also, the paintings hold that – perhaps – vulnerability because the surfaces are very thin, the top layer almost feels it could be scratched on the board. It’s a precious object – thin paint on board is quite exposed physically – that’s something I felt very strongly when I came into this space. I saw them as objects rather than as a two-dimensional image on a screen, which is something quite different.

CB: Yes, if you have a small scratch on any of the paintings […] it’s quite serious.

MK: Or on canvas, where canvas holds the paint, it’s much less vulnerable. Yes, and I think that vulnerability and fragility…

CB: So, having had a group of painters helping me to sort out the clusters…they said I was really generous with them just handling my paintings like that.

MK: Yes, absolutely, to surrender that… is a huge thing.

CB: I have no problem with it. If something suddenly chipped off what would I do?

MK: Yes, it surprised me.

Audience: Can I ask you about these forms? You could say these pictures aren’t figurative but they are figurative because there are squares, rectangles and circles which are emerging out of somewhere. When you paint do you actually … you are beginning with a blank canvas but then something comes through … presumably and each time it’s another square of another emerging sphere. Could it be different from that? These are the simplest possible forms. You talk about language and this is idiomatic, produced to the most primal shapes. It could be pentagons.

CB: It’s not triangles or octahedrons. I am not really familiar with Plato but whenever I read about him or suggest him to students we take it somewhere! (whistle) There is something about it. I am interested in the basic thing. Like the octahedron representing air. Where modernism comes into it. It’s just so complicated otherwise. If you know my work, I’ve always worked with the circle and rectangular – when I worked with the cars, the rectangular on wheels, circles, just moving, for example the painting ‘Growing up on four wheels’.

Audience: But you did have these figures as well.

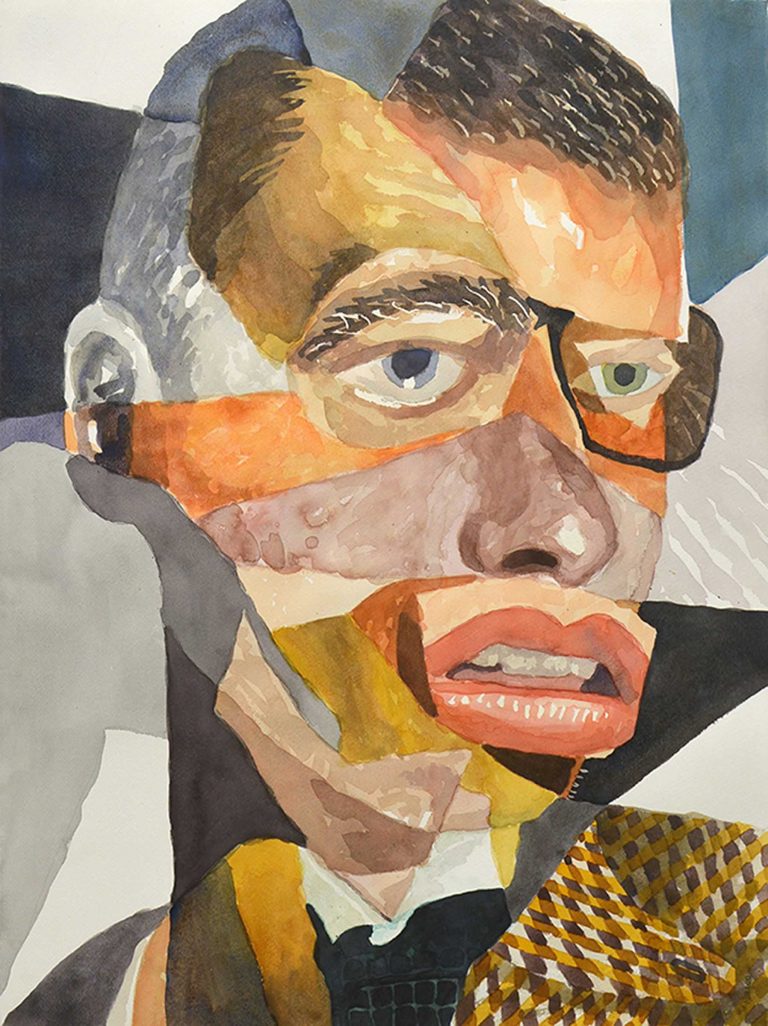

CB: Yes, in the end I had ‘Eight Jews in a Volvo’. Yes, they were figures but then the paint was very relevant: it looked like dirt and blood … the paint was more important than the eyelids and hairdo. But to go back to your question … I’ve also always used the line, which is a long rectangle…It’s a good question because I might be on a way to figuration again after having explored the mark making and the paint really deeply. But I need to feel so strongly about it – to paint figuratively, for me figuratively in the 21st century … Lucian Freud, Francis Bacon, Emil Nolde, I am on that sort of path… How would I do this now without too much ‘this of an eyebrow, this is a shoulder’ but … that it comes from inside, the body? Occasionally I do figurative work, I am thinking of figuration and portraiture.

Audience: With your titles and what you‘ve been talking about … the wound and human suffering … passions and behind all this work. But you are able to reduce it down to absolutely primal forms.

CB: It’s where we come from, where the hole is, the lacerations, where we leak, basically. We are not whole. Sometimes it’s a round shape, sometimes squary with an edge.

Audience: A square is not so organic though.

CB: I tried to work with this in [pointing to] ‘Privilege’ and ‘The length of time’.

Don’t forget all are already on a square / rectangular format, a grid really.

MK: Claudia, the last thing I want to ask you, that’s come back to me a few times when we talked about influences – be they modernist or about the body, is how your work relates in your mind to landscape? You cite Constable and Friedrich and psychological or geographical borderlines. Can you talk about landscape in relation to your work to conclude?

CB: Nature is one of my main influences. Human nature and nature generally.

Animals, plants, weather. I feel nature is my teacher. My visual decisions, the colours come from nature and the way, formats in it, the sizes of the circles and how they relate to the edges comes from human experience. There is a synergy between all interests.

MK: And Light?

CB: Yes, the engine that fires it all.

Audience: Do the seasons have a physiological influence on you for your work?

CB: Last year I worked the whole year by the sea. The sea really worked on me. It became too much… The sort of person I am I need a bit of grit and life and mess. The sea was just too …

Audience: …sublime?

CB: Yes.

Audience: … Caspar David Friedrich’s lonely figure by the sea …

CB: I lived there for two years where he painted. I go to places which have been rendered by artists…here in Suffolk it’s Constable and Gainsborough…to see with my own eyes what’s the sky, nature like. Then to see Constable’s blobs. White blobs! It’s about light. I like white. I’ve got it everywhere. But it’s also about politics. With Friedrich’s seascapes…he also looked onto Poland, Sweden, Russia …

Audience: The heritage of the German culture…have you read ‘Landscape and Memory’ by Simon Shama? Is there anything in that, where he writes about the German landscape, that influences your thinking?

CB: We are defined by trees in our culture. This book is interesting but I prefer Deacon, Maybe, Sinclar and Macfarlane, who are more regional. Shama, he’s a good thinker but I like to read by people who have walked it … been in it. That’s also more British. Real places, time, mess and beauty. Think about Beuys, but it’s very complicated, he planted 8000 oak trees in Cologne – the same the Nazi’s did. There is something going on here. Balance? I mustn’t’ get too big headed, that’s dangerous.

Audience: The oak tree – sacred to Wotan?

CB: Perhaps, but Beuys wouldn’t have said that, I guess, but more about the German soul needing roots … healing. But the Nazis would have most likely referred to the very Germanic, Niebelungen kind of world. In Britain you are more defined by the water, by the sea and these distances between things. The watery is an element in art.

MK: I guess it’s the primal thing of the paint, the fluid, movement …

Any last questions?

Audience: A really fascinating interview, brilliant!

MK: Thank you very much Claudia.

CB: Thank you.