Notes on Contemporary British Abstract Painting

Essay Terry Greene

Abstract art emerged from the United States of America in the 20th Century and has continued to evolve and flourish in 21st Century Britain.

Explore some of Terry Greene’s ideas on this subject in his essay “Some Notes on Contemporary British Abstract Painting”.

… “before the work conveys reality it must achieve its own reality, before it can be a symbol it must rejoice in being a fact, and the more it affirms its autonomous reality the more will it contain the possibility of returning us to the reality of life.” David Sylvester

When abstraction was first at the forefront of radical artistic modernity, in the earlier part of the 20th Century, the historical moment was not so unlike that of our own contemporary political moment. Global financial crisis and mass unemployment; rising nationalism; movement towards ultra right wing politics; leaps in scientific knowledge and technology are just some of the common features to both epochs. Those same issues informed the original modernist agenda which, while wavering between optimism and despair, was nevertheless convinced of the power of art and its ability to make sense of a rapidly changing world.

Artists today are uniquely placed to look back and assess the nature and development of British Abstract art since its flowering a little over a century ago. Recently a new generation of British artists seem increasingly inspired by the non-representational and are actively engaged in a re- appraisal of its merits. But whereas those earlier artists, underpinned by either spiritual beliefs or a socially utopian ideology, developed new forms of abstract art, today artists are able to encompass many of the most characteristic historical forms of abstraction.

Robert Motherwell wrote that “The function of the modern [his italics] artist is by definition the felt expression of modern reality.” And that “The past has bequeathed us great works of art; if they were wholly satisfying, we should not need new ones.” He goes on to expand, “From this past art, we accept what persists [as] eternally valuable….It is the eternal values that we accept in past art. By eternal values are meant those which, humanly speaking, persist in reality in any space-time, like those of aesthetic form, or the confronting of death.” (i)

Many contemporary artists are presently engaged in an exploration of the recovery of some themes and forms from the tradition of modern art. in an inquiry into their ‘values’ to better enable them to express the social, political, and spiritual experience of our own time. Contrary to a perceived sense of being based on a regressive, ‘nostalgic’ attitude, abstract painting is perhaps a unique ‘platform’in offering such a direct means to ably acknowledge the co-existence, for example, of mathematical order with the bodily. It’s a combination we as a society are increasingly forced to encounter and is central to how our relationship with the world is increasingly changing.

In an article, from 2016, ‘When music can be made on a screen, we lose abstraction’, introducing a new app for the iPad, which enables anyone to make music on a touch screen by moving shapes around with their fingers, Russell Smith makes the following observation: ”this pretty technology can be seen as part of a larger tendency in our lives towards the graphic representation of everything. Very little is abstract any more. Sounds and words and numbers are all spinning and glowing, colourful three-dimensional objects in our minds, because that’s what they look like on our screens. When we check the weather forecast on our phones we see an image of a stormy sky or a sun. That hits us before the actual temperature does.” (ii) We detect in Smith’s (online) article, which navigates a space between a review (of a new ‘product’) and a critique, this sense of a certain condition of loss being communicated. (Interestingly a loss of the abstract in the realm of the technological).

We perhaps all feel that there appears to be this generalised sense in our culture that something may have been lost, this power of the screen and the Internet, in this the ‘information age’, hovers over us. An ever present charged border between the human and the technological. And it is in perhaps meeting this challenge, of offering a site for negotiating a ‘mediated life-world’ is where contemporary abstract painting differs to previous incarnations.

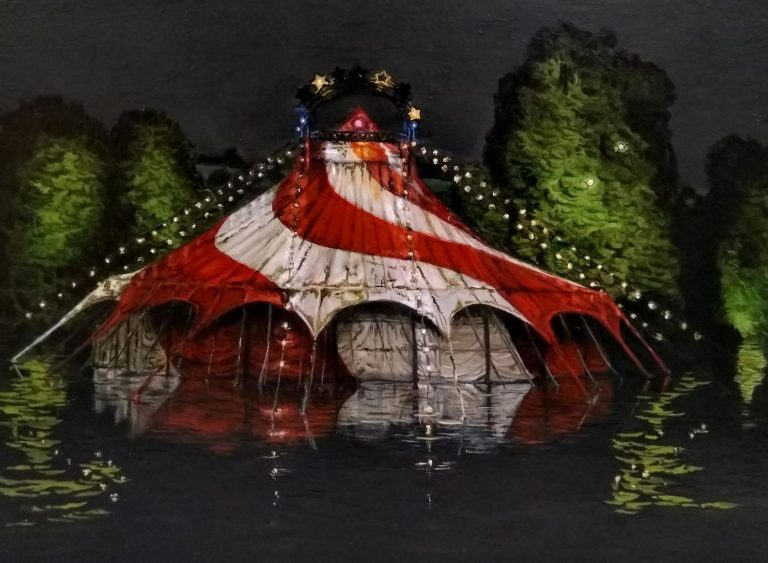

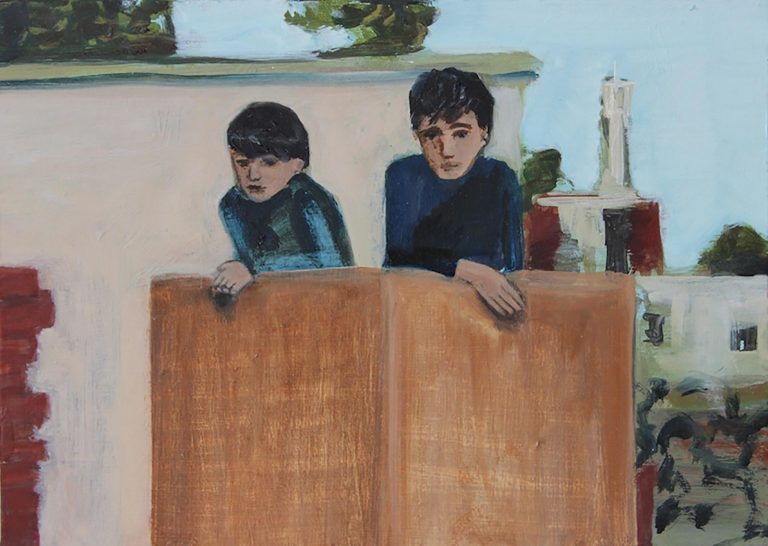

As might be expected, the paintings of Contemporary British Abstract Painters are as rich and as varied as one would imagine. Any partial list of some of the features of Contemporary British Abstract paintings might include both geometric or biomorphic compositions, irregular grids, lattice and stripes. Some CBAP’s employ a large vocabulary of smudges, stains, spray paint, flecks, dribbles and painterly marks, in saturated colour – others employ almost-monochromatic fields. Gestural techniques are mobilised on the painting surface, perhaps re-enacting the conversation about control and freedom happening in the wider world. The expressive gesture, serving as reminder of the material domain of the human body – a visceral mode of abstractly figuring the bodily in and through the material of paint.

Contemporary British Abstract painting ably evokes a host of themes, from landscape to bodies and signs to architecture, and much more. At the level of reception we may feel the artists are tangentially exploring subjects: such as commodity culture, aspects of the social, personal, or art history. In some instances the process of painting is itself the content – or the content might be discovered, revealed through the very act of painting. “Its order as well as its subject-matter can be evolved in the act of painting, for the ultimate reality of painting lies in painting.” (iii) David Sylvester

Some of the artists produce work which deliberately resembles something coarse, inelegant and provisional. Others are deftly executed or cerebral. When someone chooses to make a surface, that painting will largely refer to that surface. When they choose to include a form or an outside reference in a painting, they are knowingly opening it up to another world of possibilities. In some instances artists works offer up their graphic field to be taken in at once. Seeing it and getting it fast as – an intentional acknowledgement of todays reality of the endless distribution of digitised images and viewing on all manner of digital devices.

Contemporary abstract paintings re-emergence appears to answer deep cultural concerns at this time, aiding us, as I believe that it does, to begin to make sense of our digital, screencentric experience today. There’s little need (or will) for any binary position to be taken, it’s clear that artists don’t have to choose between the computer and the hand. But rather, it’s in an ongoing conversation between the two that I believe has given painting its latest surge in vitality.

Terry Greene, 2017

i. Robert Motherwell, The Modern Painter’s World, Written in 1944 and presented as a lecture at a conference at the Mount Holyoke College, South Hadley, Massachusetts.

ii. The app is called Rotor, which enables anyone to make music on a touch screen, and record it and alter it, by moving shapes around with their fingers. Published Wednesday, Oct. 19, 2016, in the Globe and Mail, article by Russell Smith, a Canadian writer and culture columnist.

iii. David Sylvester, English Abstract art, 1957, From his collected writings: About Modern Art, Critical Essays 1948- 97, published by Pimlico, 1997.