Narbi Price: Artist of the Month

Artist of the Month September 2021: Narbi Price, selected and interviewed by Paul Newman for CBP.

For September’s artist of the month feature Narbi Price discusses his Lockdown series and his painting practice in general.

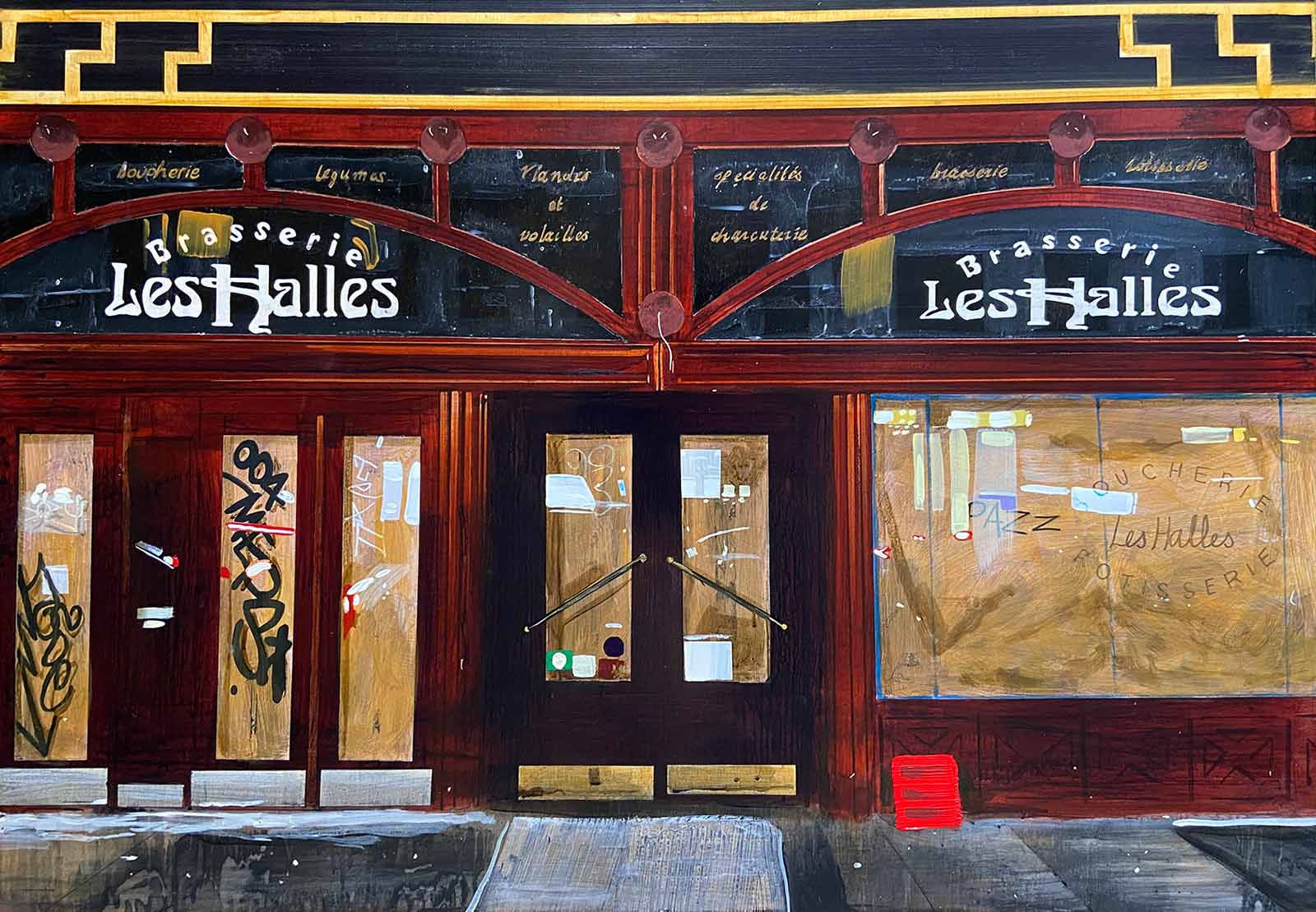

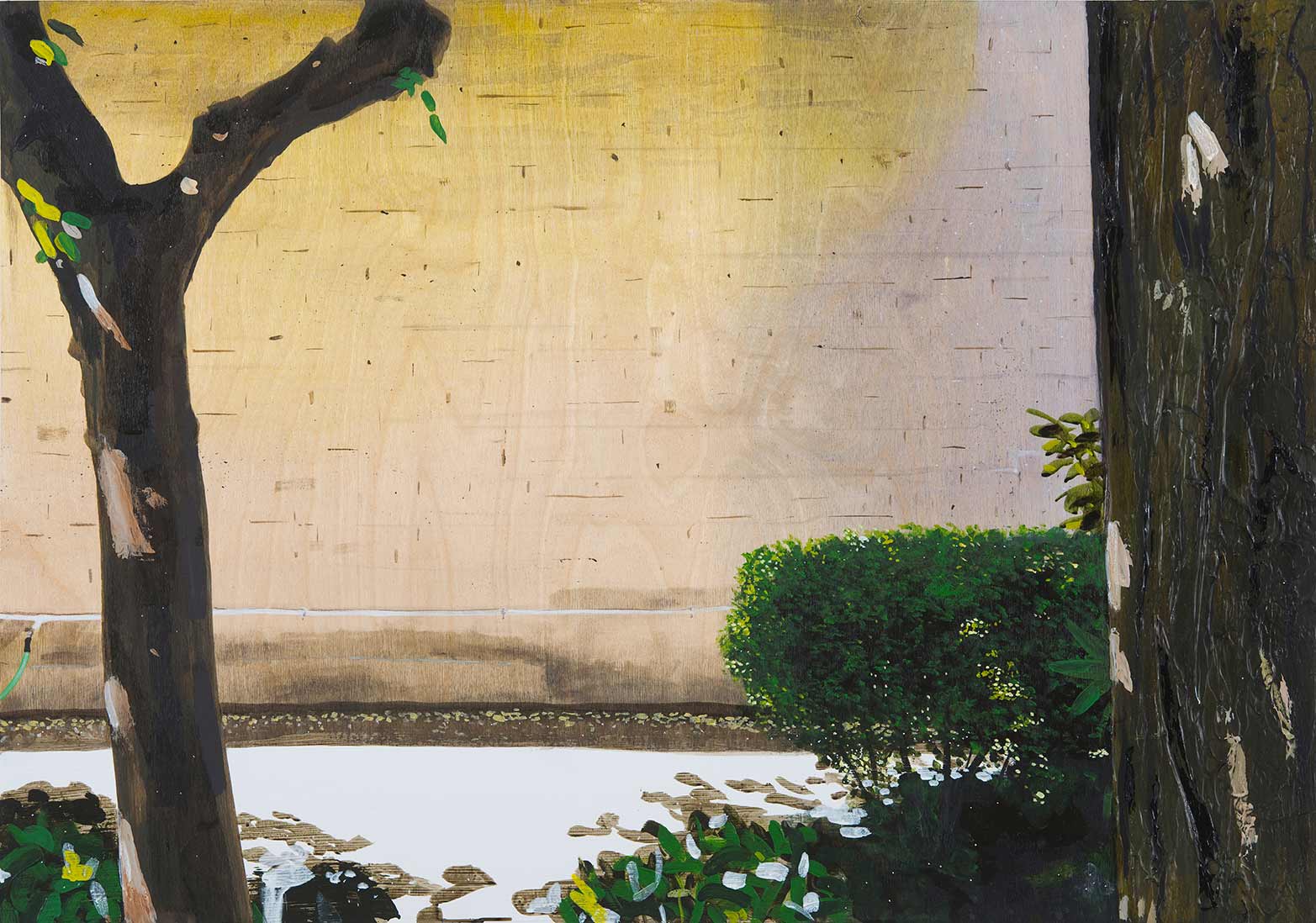

Narbi Price’s work involves journeys to specific places that have witnessed a range of events – variously historical, famous, personal or forgotten. He researches the precise location of a chosen event and, working from photographs taken at the site, makes paintings in the studio focusing on the abstract, formal and painterly qualities of the resultant images, using the language of abstraction to simultaneously acknowledge and disrupt the representational image. The paint is transparent, opaque, glossy, matt, dilute and impasted, often within the same work. The viewer is not immediately made aware of the specific histories of the sites and is given space to wonder about the multiplicities of events that might have taken place, an effect heightened by the painting method. The experience of the work shifts as we become aware of the provenance of the depicted sites.

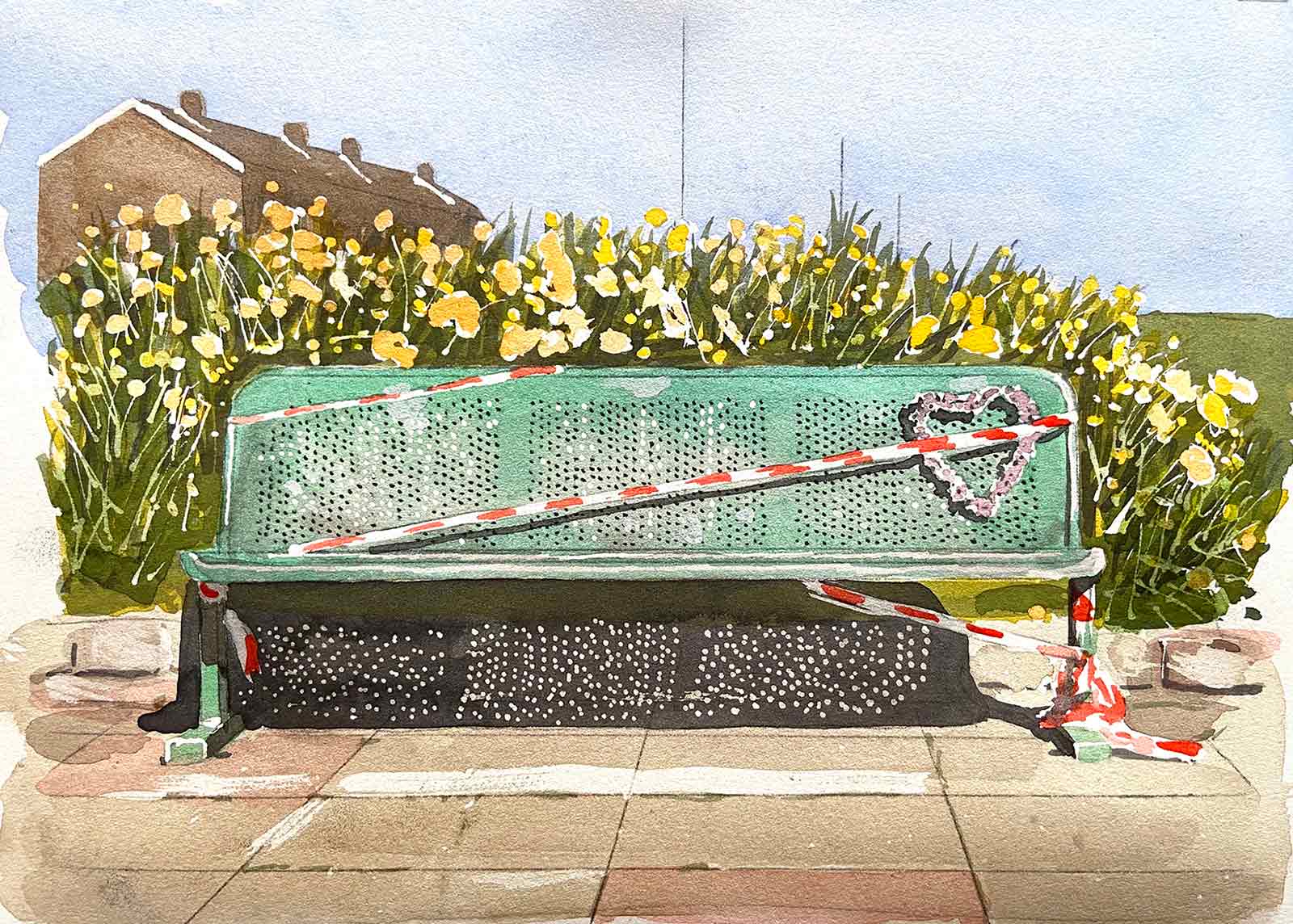

CBP: Your Lockdown paintings of public benches taped off are both of iconic and matter of fact. Can you discuss the circumstances of the period, the affect on your practice and the choosing of this motif for a series of work?

Narbi Price: Like many other artists, I was unable to use my studio during the lockdown and I had to think of a way to make work in different circumstances. Downsizing was the first step, to a size that I could work to at home, and I started to think about drawing and painting as work, as labour. I’ve spoken elsewhere about the seismic dynamic shift that Matthew Burrows’ ArtistSupportPledge initiative has had on how a certain price point of work is conceived, produced and collected, but it was very much with this in mind that I produced these smaller works. I came up with a logic system – how could I produce work at the £200 price point without compromising the integrity of the value of previously collected work? The notion of making work as a job of work became key – I decided that I would spend no more than a day on any one piece, thinking about a day rate for a visiting artist in a HEI for instance. In this way the idea of ‘work as work’ became important, not only in the pricing but also in the approach to the making. I had noticed several friends posting photos online of public benches wrapped in red & white barrier tape, to prevent them from being used, people also started to send them to me, telling that they looked like something I’d paint. And they did. So I did.

The paintings really struck a chord with a lot of people and all sold within minutes of posting on social media. People then started saying that I should do a book of them, and they were right again! I crowdfunded the production of a publication with 40 paintings, accompanied by a new essay by the writer, broadcaster and filmmaker Michael Smith. Narbi Price: The Lockdown Paintings is available from my website, Waterstones and Foyles. CBP mailing list subscribers can use the discount code CBP50SEP for 50% off for a limited time when ordering directly from https://www.narbiprice.co.uk/product-page/narbi-price-the-lockdown-paintings.

CBP: The Pandemic bench series are in watercolour. Can you talk about how you’ve found working with this medium compared to with your usual working practice with acrylic paints?

NP: Watercolour was a huge challenge and required significant adjustment to how I applied paint, and conceived of the construction of the images. Being stripped of all of my arsenal of painterly nuances and tricks, developed over many years working with the same medium was in some ways, liberating, it forced me to think in a different way. I very much learned on the job, but the process of making so many works in such a concentrated period of time catalysed the learning, and now I think I know what a ‘Narbi Price’ watercolour looks like.

CBP: Looking closely at your paintings online and especially in the few I’ve seen in exhibitions; you can see lots of natural and instinctive things happening on the surface and within the layers of the painting. I’ve heard you discuss the importance of experimentation with the medium and It’s like the representational urban landscape subject matter provides a scaffolding to continue to explore the possibilities with the medium. Can you talk your own push pull relationship between representation and the medium of paint?

NP: I’ve sometimes said that I feel like an abstract painter stuck in the body of a representational one. It comes from a frustration throughout art school of how figurative work would be discussed in comparison to abstraction. People would discuss gesture, association, colour relationships, application etc. when speaking about abstract work, whereas the discourse would purely focus on what the painting was of, when talking about representational work. My approach to painting since then has been to try and swerve this and make figurative paintings that use the same repertoire of technical possibilities that so often come to the fore in pure abstraction. In some ways, I use this to subvert the depicted image: I want the paint to work hard, to not necessarily lay back into the image as a window frame or area of grass or whatever. It’s unapologetically a lump of paint, a drip, a smear, a hard masked edge, a ridge etc.

Untitled Gutter Painting, acrylic on canvas, 91 x 122cm, 2014

Untitled Yard Painting (Harold), acrylic on canvas, 91 x 122cm, 2015

CBP: Abstraction comes into play with formal composition and as well as the medium. I remember a lecture at art School which used Vermeer’s Little Street painting with the red shutter as an early example of abstraction within representation. With this in mind can you talk how you compose your images, with the source photographs you make on site and whether you make changes in the compositions of the studio paintings?

NP: I love that particular painting, and along with Thomas Jones’ Wall in Naples, I go back to it time and time again. The compositions are always constructed with abstract concerns forefront in my mind. The process of photographing the sites becomes analogous to drawing, I’m thinking about how I divide the rectangle in very formal ways. I don’t make any edits at all, all of the composing, cropping, editing etc. happens ‘in camera’. I’m already thinking about how I might approach various treatments in the painting when I’m viewing the site – this part might be heavy impasto, this one veils of transparent veils and so on.

CBP: Do you always work from photographs, or do you ever draw / paint plein-air on location?

NP: It’s always photographs, for very practical reasons, the paintings are very methodically worked up, which takes a long time, with numerous stages of transparent colour needing to dry and so on. Although, as I said, I see the photographic process very much as an act of drawing.

Untitled Bus Stop Painting (Colliery), acrylic on board, 50 x70cm, 2018. From the Ashington Paintings series. Private collection UK.

Untitled Fence Painting (Colliery), acrylic on board, 50 x 70cm, 2017. From the Ashington Painting series. Private collection UK

CBP: History is an important as providing context to your work. You talk about needing more than just painting a scene through aesthetic choice and your research of sites of historical interest, although these sites have naturally changed significantly through the layers of time with progress and development. Can you talk about the notion of trace histories and the obscuring of an event through the changes to a site as an aspect of narrative in your work?

NP: It began shortly after my MFA as a device to remove my own aesthetic taste from my paintings to a degree, as well as a method to travel to parts of cities I would otherwise have no reason to go to. The idea of pilgrimage is a very human thing, from the most prosaic instances (TV news reporting from a site, putting flowers on a grave), to more loaded examples (visiting sites of atrocity, or disaster). The need to feel some of sort of connection with the past in a physical manner is perennially prescient, and my interest in it as a starting point for making paintings places myself and the viewer within a framework that becomes difficult to nail down, various significances transient, important only to certain participants. History and histories of sites focus very much on singularities, and my paintings aim to be open to the multiplicities of events that have occurred at any given site, recorded or not, deemed important or not.

CBP: A well as specific contexts to individual works, there is a broad visual narrative of depicting urban infrastructure, old and new with elements of dereliction and nature. You did your PhD on the Ashington group (The Pitmen painters). I wondered if there are underlying politics to your work in regard to social histories or capitalist development?

NP: The small P political is certainly a motivating factor in the selection of some sites, and arguably always there whether or not I intend it to be, or consider it to be personally. This isn’t however something I always seek out, it very much depends on the event I’m researching and how the site has changed.

CBP: I presume you are back in your studio now. What are you currently working towards? Are you carrying forward any aspect or approach from your lockdown working practice, for example the Pandemic bench series or making work for the Artist Support Pledge scheme?

NP: I’m currently in the middle of moving studios from B&D Studios, housed in Commercial Union House, in central Newcastle where I’ve been for around 10 years. The building is set to be demolished as part of the billionaire Reuben Brothers ‘redevelopment’ of Newcastle city centre, so it’s with some sadness but also excitement that I’m moving to a larger space at the Biscuit Factory studios.

With a couple of exceptions, the bench paintings were never publicly exhibited, they went directly from my house to collector’s houses. It felt like a huge shame to let the images not have wider exposure than that, so I decided to revisit some of the Lockdown bench images in acrylic and at a larger size 70x100cm. This has allowed me to really ‘get into’ the painting of them, to reconsider the imagery and allow it a more intensive handling. One of these is currently on show at Sunderland Museum & Winter Gardens as part of ‘Where We Are Now’ and two more are set to part of Middlesbrough Art Weekender from September 30th – October 3rd. A selection of work from The Ashington Paintings series is set to be shown in at the Alan Baxter Gallery in London opening on October 4th, alongside CBP artists Judy Tucker and Mandy Payne, and Trevor Burgess and Jonathan Hooper in a show called ‘Where We Live’, looking at how we have each made longitudinal studies of localities.

About Narbi Price

Born 1979 in Hartlepool, Narbi Price lives and works in Gateshead and Newcastle upon Tyne, UK.

He was the Journal Culture Awards Visual Artist of the Year 2018, and the winner of the Contemporary British Painting Prize 2017. He was featured in Phaidon’s Vitamin P3 – New Perspectives in Painting and was a prizewinner in the John Moores Painting Prize 2012.

He has recently completed an AHRC funded PhD at Newcastle University in partnership with Woodhorn Museum.

Recent solo exhibitions include 2020; ‘The Ashington Paintings | Redux’, XL Gallery, Newcastle University. 2019; ‘All I Start Will End’, Herrick Gallery, London. Recent group exhibitions include 2021; Where We Are Now’, Sunderland Museum & Winter Gardens, Sunderland, ‘Unkempt – Shifting Aesthetics in Representations of Landscape’, Messums Wiltshire, Tisbury, ‘Figurative Art Now’, Mall Galleries, London (online), ‘Bus Stop Gothic’, (online), ‘Pretty Ugly’, Thames-Side Studios Gallery, London, ‘The Lockdown Interviews Exhibition’, The Cello Factory, London. 2020; ‘Vitalistic Fantasies’, The Cello Factory, London.

Further Links:

https://www.narbiprice.co.uk/product-page/narbi-price-the-lockdown-paintings