Nicholas Middleton: Artist of the Month

Artist of the Month January 2023:

Nicholas Middleton, selected and interviewed by Paul Newman for CBP.

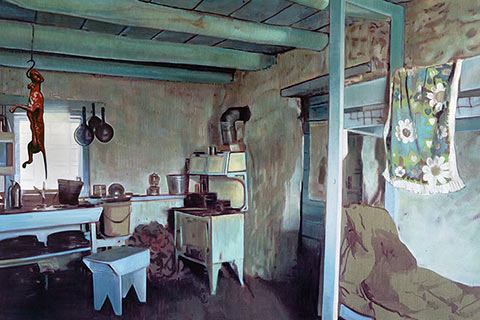

Fundamental to my practice is the image. In a world of proliferating images, examination of how the image, tethered to reality, is constructed, processed, displayed, has underpinned my approaches as a maker of images, through painting and its histories.

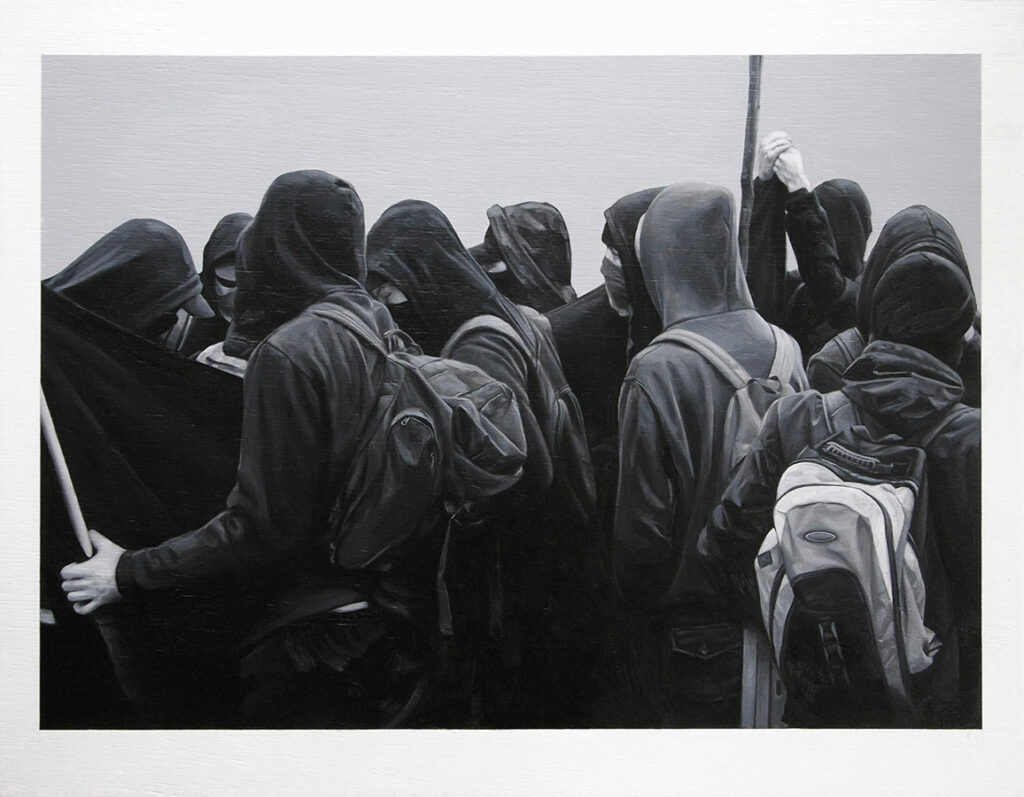

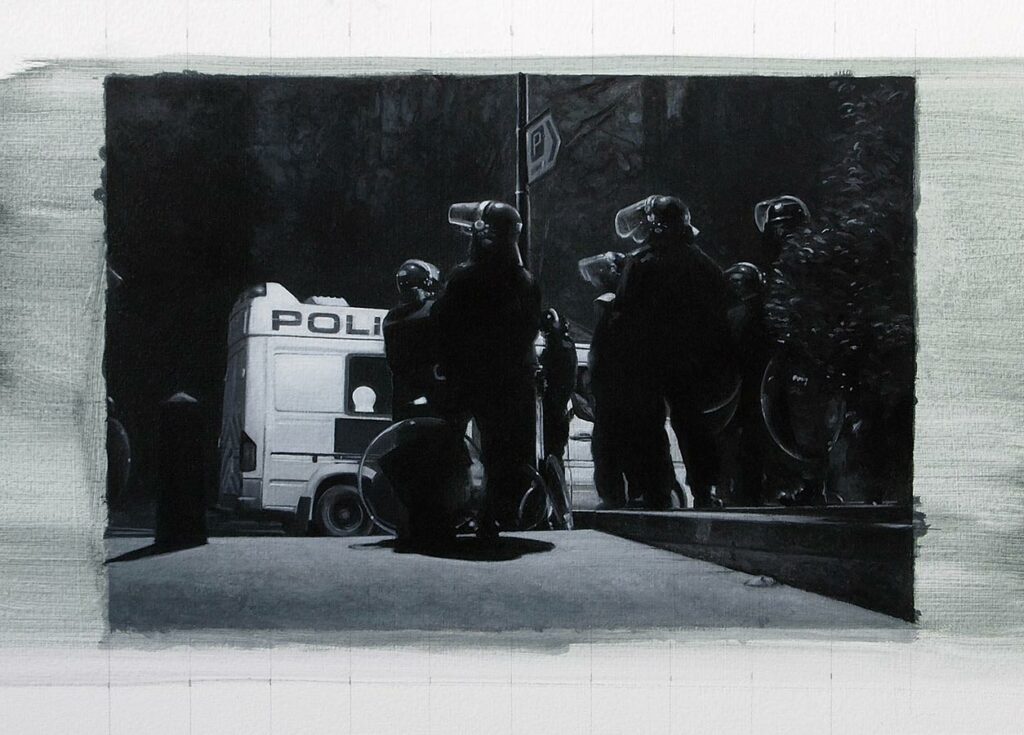

CBP: Your painting has conversations with the photograph, with a range of imagery from apparent reportage of urban riot police and street workers to staged tableaux. Can you introduce the types photographic source imagery you are interpreting through your paintings?

NM: Almost without exception, the photographs I use as reference material are my own, and are usually shot on film, although I have also been working from digital photographs more recently. Any sense of ’apparent reportage’ is often just that: sometimes I go looking for subjects for my paintings, sometimes the subjects find me. Often I take photographs without any intention that the subjects might become a painting, merely as a record of something being visually interesting at that moment, and then sometimes I do take photographs specifically as source material for a painting, and, in addition, on occasion I have created a scenario or mise-en-scène to photograph for a very specific idea of a painting. Especially with film photography, looking at the images at a remove from the subject, sometimes months or even years later, something then about the photograph suggests it might make for the basis of a painting, and sometimes (but not always) the act of painting confirms this.

The very ubiquity of photographic or lens-based representations, which are everywhere in the contemporary world around us – which has something of a neutralising effect – is, in some senses, an overarching concern in my work: as someone interested in images, it would be impossible to ignore this shift in visual culture, and painting as a form of image-making now has to contend with its relation to photography (I would find it hard to make a painting now and pretend that photography did not exist) – but I think perhaps I am still working within a slightly-older mode of photography, as someone who grew up in an essentially pre-digital world, and learnt photography with film cameras, working in the darkroom with physical materials.

CBP: A compelling aspect of your work and its reference to the photograph, is the relationship between the subject and the viewer. Two different examples: 1. the perspective of looking at a photograph as an object within the painting and 2. the subject of a photographer or office worker absorbed in their work and the point of view of the encounter presented to us. Can you discuss some of the subject / object and viewer relationships in the work. And is there any element of Psychoanalysis; Scopophilia (the pleasure of looking) and voyeurism?

NM: The idea of the viewer – that I have in mind some form of ideal viewer for my work when I make it – is something that I’ve always been conscious of, but in some of my work there’s a sense of a doubling-up of what visual art enacts, visual aesthetic pleasure, as a theme, with the viewer engaged in an analogous relationship to that of a figure in a painting for example. There is a recurrent theme of a figure in an absorptive moment in some of my paintings, often working with the necessary fiction of being compositionally arranged for legibility to the disembodied and absent viewer, without explicitly acknowledging that this is the case, as with the ‘tableaux’-style paintings in particular. Then there is also a theme in my work of an encounter with the photograph as an object, a reminder of its object qualities, but also how it is used in the external world, with postcards, posters, murals and other iterations of the photograph infecting the spaces of everyday life.

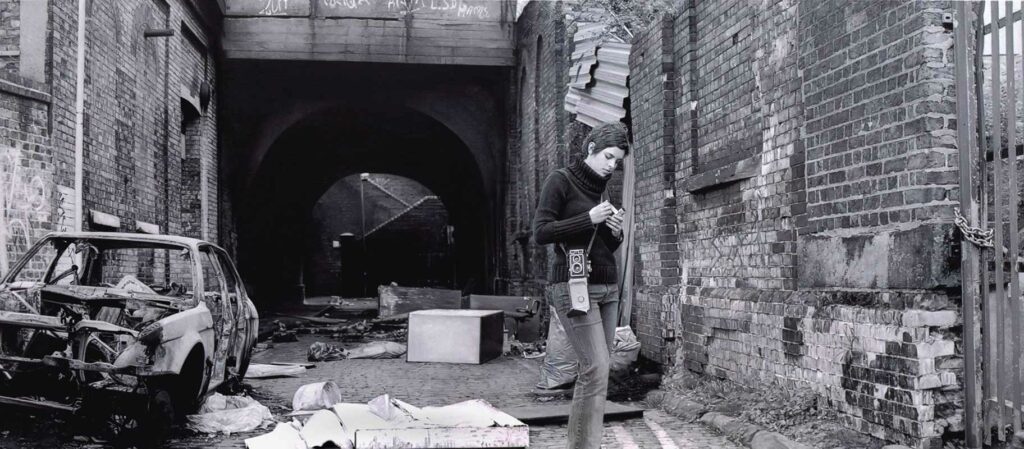

CBP: In your essay for your painting ‘Scene from a Contemporary Novel’ for the John Moors Painting 24 Prize you discuss what might not be apparent in your painting; it is sometimes based on a staged tableaux constructed from a montage of photographic sources. Can you talk some more about this process. And does it vary between series of works how they are constructed?

NM: ‘Scene from a Contemporary Novel’ was the largest and most ambitious painting I had made up to that point – it was painted specifically to enter the John Moores Painting Prize in 2006, and, being selected, it was successful on that level at least. The composition was based on thirteen photographs if I remember correctly, digitally stitched together. This had broadly been visualised beforehand (some of these paintings had a thumbnail sketch, but no more) and then I took dozens of photographs in the location, of the location and of the acquaintance who was kind enough to pose; the burnt-out car was photographed somewhere else, entirely separately, but was necessary as a compositional counterpoint to the figure. This was a way of working, used on several large canvases made over a period of five or six years. (In many respects, this relates more directly to the next question: an approach inspired in part by Jeff Wall’s large-scale photographs, in turn inspired by Manet and other nineteenth-century painters, in my case, this would also include some Degas, early Millais, Ford Madox Brown, for example, but also further back to Joseph Wright of Derby, Vermeer, Caravaggio, Artemisia Gentileschi). With these works, there is a particular mode of address to the viewer, something that projects forwards historically, which becomes theatrical or cinematic. This stemmed from a simple idea of wanting to make the kind of paintings that I liked to look at when I was younger, a motivation less important now, as I largely work on a much smaller scale.

This isn’t an approach I’ve really used for a number of years. However, some of these operations persist into the more recent, smaller work: cropping, flipping the orientation of a source image, sometimes joining together more than one photograph, editing out backgrounds or swapping them out for something else, although some paintings are relatively straightforward transcriptions from a single source photograph.

CBP: With the notion of staging a scene you talked about a range of references from Pre-Raphaelite paintings to Jeff Wall’s constructed photographs which sometimes reference art history painting. Can you discuss some of the wider contextual reference points in your work?

NM: Making paintings at this point in the history of images and the development of image technologies – as I see myself as being interested in images far more than materiality – perhaps I wouldn’t make paintings without the pre-existing, long history of the medium (philosophically, in some small sense, each new painting is in a conversation with every other object considered to be ‘a painting’ as instances of possibilities of the medium – although I am far from any attempt at expanding the field of painting that this might imply, only that I am working with well-worn automatisms of the medium, but sometimes quite consciously).

Apart from some of the artists already mentioned, there are almost too many and various contextual reference points to discuss without giving specific examples relating to specific paintings: generally, I have always been attracted to eras in the history of painting which Peter Galassi in ‘Before Photography: Painting and the Invention of Photography’ describes as having ‘denser’ applications of perspective (very broadly, the fifteenth, seventeenth, and nineteenth centuries, as well as being geographically determined, again very broadly, Florence, the Dutch Republic, post-revolutionary France) – for me this often seems to align with an interest in a certain type of ‘realism’, however that’s defined. More contemporary references are photography and film, but again, broad in scope and hard to be specific.

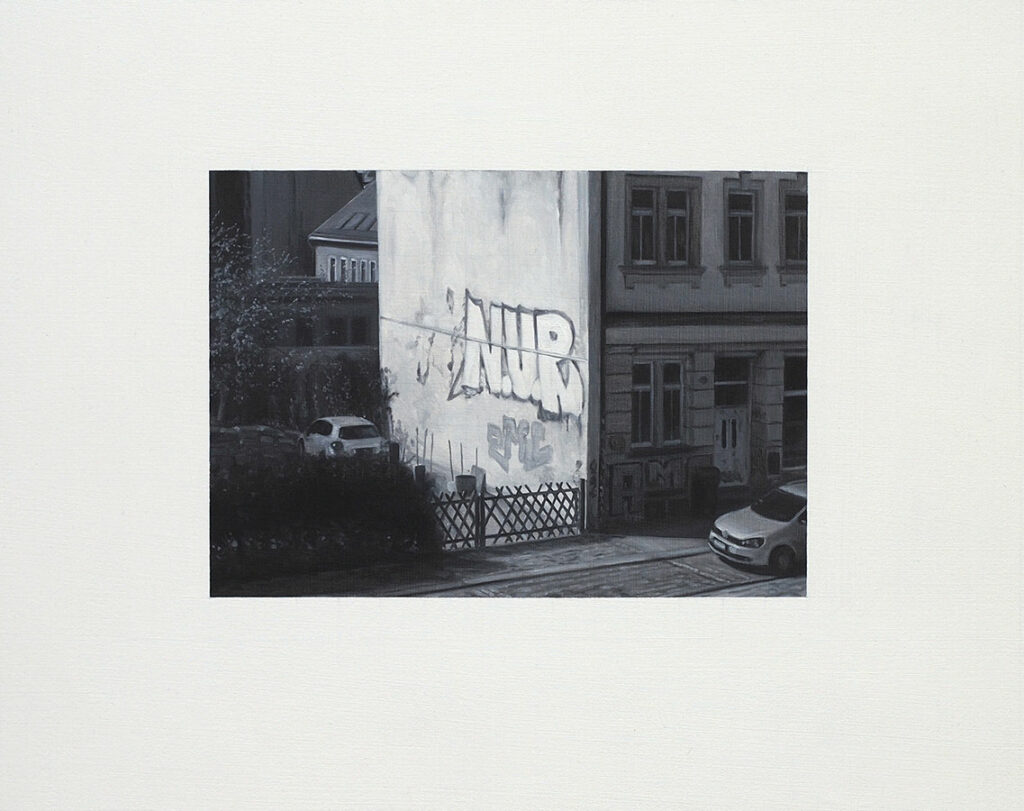

CBP: Your work is predominantly black and white, or monochrome. Can you talk more about this, and how you mix your monochromes on the pallet?

NM: The use of monochrome has a direct relationship to photography in that most of the photographs which end up as the source material for my paintings are taken with black and white film, although much of the time these aren’t necessarily taken with the aim of producing paintings (I did also make some still life paintings over the last couple of years which were from observation, but in monochrome, which kept – perhaps with an element of paradox – a ‘photographic’ association). The use of monochrome in painting has a long history, but often in referring to other mediums: usually to demonstrate the capacity of painting to encompass the look of drawings and prints, long before photography, so this may be something of a continuity. In addition, I enjoy working with restrictions: once some fundamental choices have already been decided, other decisions become more important, concentrating on other aspects of the work. In practical terms, I usually use one, sometimes two different whites, and one specific black pigment, although I have occasionally had to mix up my own black from two or three different pigments. Unless I am working with large areas, the paint is just mixed directly on the palette as and when needed, that is, I don’t work out a range of greyscale tones beforehand, and, in an ideal world, when things are going right, I work ‘alla prima’ as much as possible, especially with larger works on canvas, but also now with smaller works on paper, such as ‘Late Afternoon’, with as few retouchings as I can, although there are often modifying layers, particularly with more complex works,and notably with trompe l’oeil paintings, to achieve transparency and translucency, with painted masking tape being a good example of this.

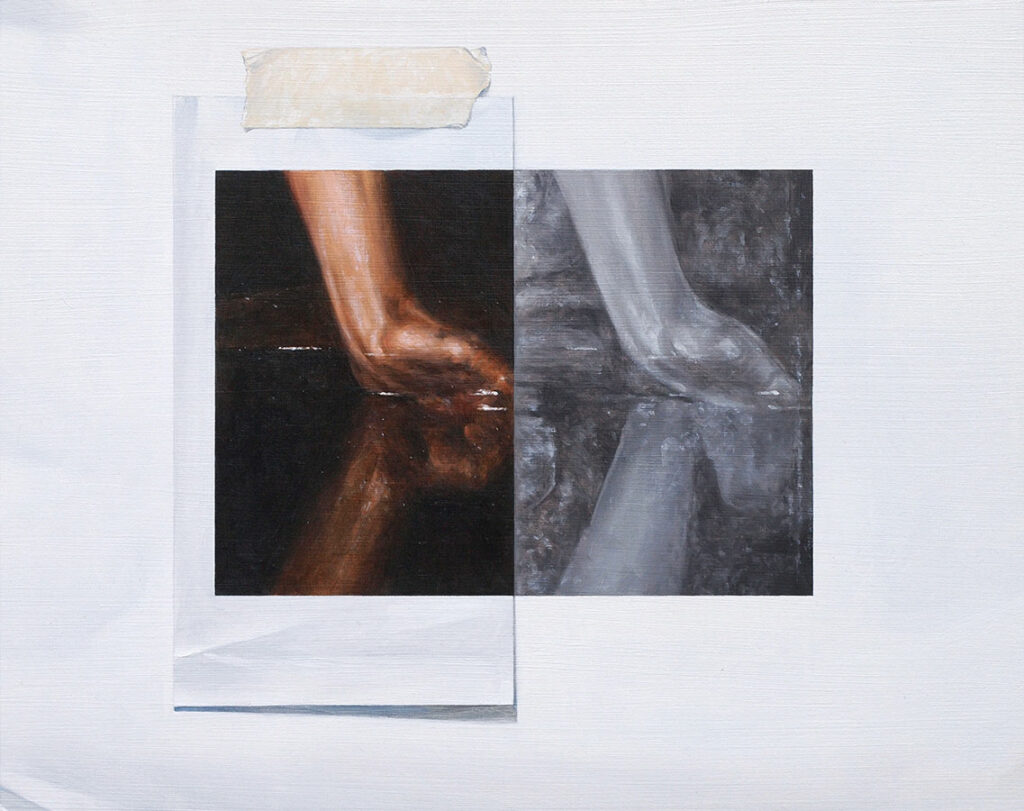

After Carel Fabritius, oil on paper, 24cm x 30.5cm, 2022

Interface (After Caravaggio), oil on paper, 24cm x 30.5cm, 2022

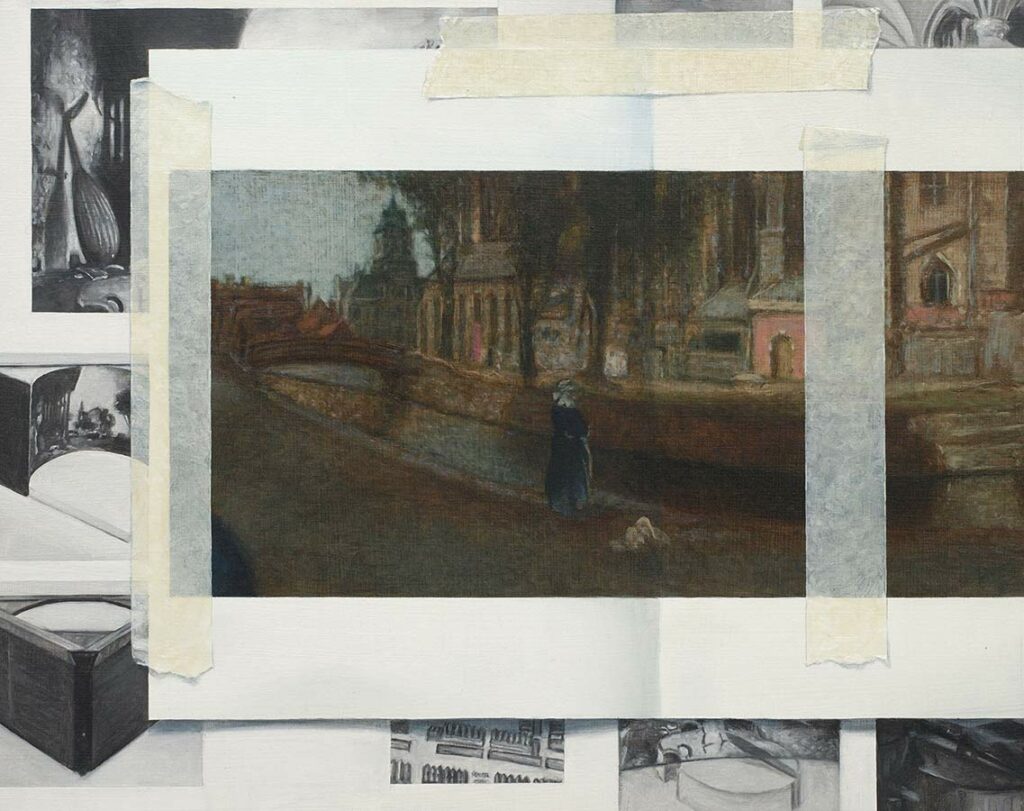

CBP: Recent work include small scale tromp l’oeil style paintings of sketches or studies taped to a studio wall. They trigger for me a connection with Lucie Mackenzie’s paintings of cork mood boards. Can you talk about the works in this series?

NM: I made a few paintings with trompe l’oeil aspects many years ago, in the early 2000s. I liked the ‘quodlibet’ approach, where it is possible to create something like a visual argument by bringing together disparate elements, like a form of collage or montage, perhaps. I’d long had an interest in aspects of trompe l’oeil, but seeing the Cornelius Gijsbrechts exhibition at the National Gallery in 2000 was must have had an influence, especially his painting of the back of a canvas, which seemed strikingly modern in sensibility for something painted in the mid-seventeenth century. In some of the more complex trompe l’oeil paintings there’s also an aspect of improvisation that I enjoy, much more than my other work: I might start a painting with just one or two elements, and then add to it, reacting to the composition as it grows. I also like the inherent play with the flatness of the picture’s surface and the possibilities of illusionism – which also appeals to the sense of touch as well as sight. The more recent return to trompe l’oeil was partly through developing my approach to making work for the artist support pledge, having established a set of parameters, and then playing with these (such as the integral white border surrounding the image, which in some of the trompe l’oeil work becomes the background behind the image with a simple shadow, or using painted masking tape to create a frame, as in Conveyor Belt). It was also a means to explore and quote, directly, isolating details of the work of other painters, work that I’d been looking at recently.

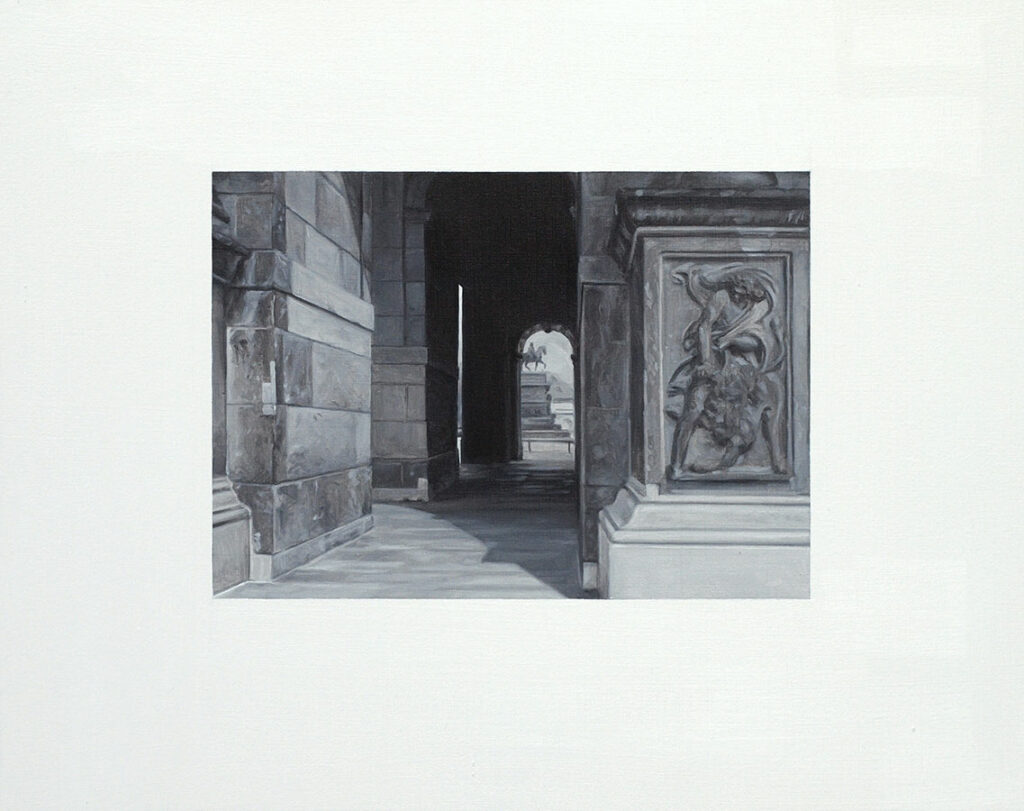

CBP: Your most recent Instagram post ‘Ideal City’ has a De Chirico feel, can you discuss this work?

NM: This painting is based on a photograph I took in Dresden, and, as with my working processes as already described, at the time I took it, I wasn’t necessarily considering it for a painting. However, the strong single-point perspective, looking through one of the Zwinger’s gatehouses to a distant equestrian sculpture, had something of a Renaissance feel (Dresden, after all, earned the title of the “Florence on the Elbe”), and I had recently been reading Hubert Damisch’s book ‘The Origin of Perspective’ in which he writes about a trio of Renaissance townscape pictures with uncertain attributions, two of which are given the present-day title ‘The Ideal City’ (one wonders if De Chirico knew these paintings, two of which are without figures); the subject of my painting had certain affinities to these, but the title also suggests something about the ‘unreal’ quality of Dresden, reconstructed after its destruction in the Second World War, a reconstruction aided in part by the paintings of Bernardo Bellotto – whose work has the look of the camera obscura about it, and who I’ve referenced in other recent paintings.

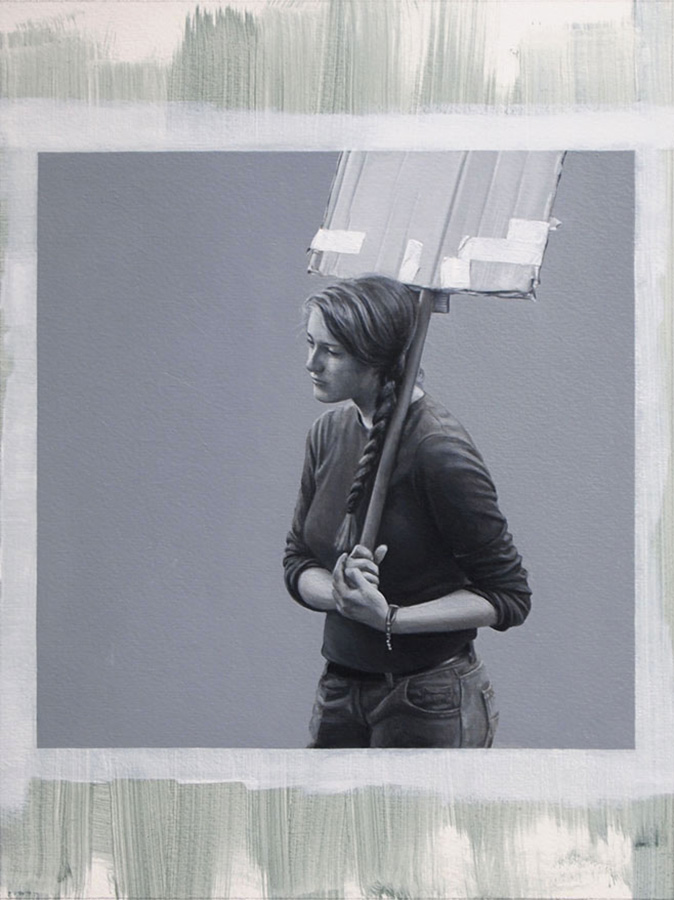

CBP: Woman with Placard feels like a staged interpretation of a necessary protest distilled to an essence of the subject in a resigned or determined, though uncertain struggle for our future. Can you discuss the construction and narrative of this painting?

NM: Early in the 2010s, I made a number of works around protests and demonstrations, mostly as I was going on a lot of protests and demonstrations, which naturally fed into work I was making. It felt like a necessity at the time, even if ineffectual, a moral duty not to acquiesce with the prevailing political directions which have led very much to where we are today. Woman with a Placard was not staged: it comes from a photograph taken when the Occupy movement made their protest outside St. Paul’s in London over a decade ago. As photographed, the placard had a slogan, but I was drawn to the homemade quality, the use of cardboard and tape. Making this blank and removing the background, takes away its specificity, making it a roughly contemporary ‘any time, any protest’. I suppose, as a result, the painting as a whole could stand in for a sense of structural inequality, and also the individual against larger, impersonal forces.

CBP: How has producing works for the artist support pledge influenced the making of your work?

NM: In summer 2020 I began making work for the artist support pledge. Initially I worked on discrete sets of paintings at a time, in groups of five, around a theme. To begin with the paintings were all based on already-existing photographs, and I treated it like an aesthetic problem or exercise, coming up with five paintings around the idea of shadows, or mirrors, or wrapping, or the very idea of ‘support’, or the backs of things, or the blocked path into pictorial space, or the double, and so on. When finding source material I might have two or three photographs which strongly represented the central idea, which meant I was then in the position of trying to complete a set, often forcing me to think more creatively about what might fit. These were all made to a specific set of parameters, oil on paper, all the same size, initially all in horizontal format, black and white, with a defined image area and an integral painted white border, and only later did I begin to deviate from these self imposed rules, partly I suppose as it was difficult to sustain this approach after making quite a number of paintings, and, as I mentioned with regards to trompe l’oeil painting, I did begin to play around with the format I had designed for myself, as well as reworking the occasional older painting which I had never quite been satisfied with. What engaging with the artist support pledge did do was that, through necessity, it genuinely reinvigorated my practice as a painter.

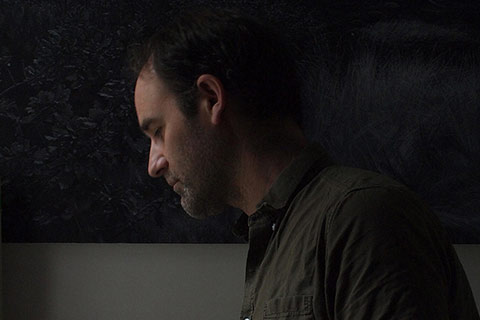

Nicholas Middleton studio

Nicholas Middleton

Nicholas Middleton was born in London in 1975. He studied at London Guildhall University 1993-94 and Winchester School of Art 1994-97 and is currently undertaking a research degree at the Royal College of Art. Solo exhibitions include ‘Black & White Paintings’ Arch Gallery, London, 2010 and ‘Provisional Cities’ The Crypt at St Marylebone, London, 2013. Group exhibitions include ‘Documentary Realism: Painting in the Digital Age’, The Crypt at St Marylebone, London, 2015, ‘@PaintBritain’, Ipswich Art School Gallery, 2014, ‘Towards a New Socio-Painting’, Transition Gallery, 2014, and ‘Francis Bacon to Paula Rego’ Abbot Hall. Kendal 2012. He has shown seven times in the Summer Exhibition at the Royal Academy of Arts. Exhibitor in the John Moores Painting Prize 2004, 2006 (Visitors’ Choice Prize), 2010 (Prizewinner and Visitors’ Choice Prize), 2014 and 2016.