Simon Carter: Artist of the Month

Artist of the Month February 2023:

Simon Carter, selected and interviewed by Paul Newman for CBP.

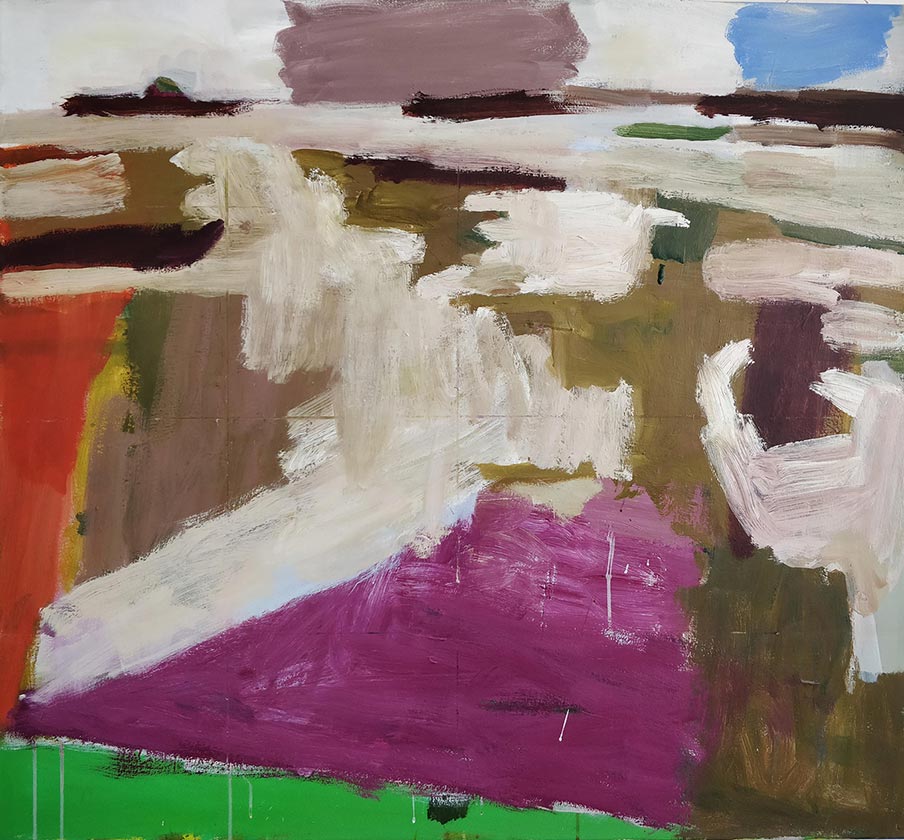

My work is based on the stretch of Essex coast where I live and have my studio. This coast is where the gardened landscape of East Anglia starts to fall, literally, into the spare and elemental spaces of the North Sea; where any idea of landscape as static and timeless is replaced by a sense of dynamic flux.

I use the elements of the coast, the creeks and estuaries, saltings and seawalls, as an archive of shapes and colours, of weather and of objects, trying to find a dynamism and passion in the paint that will match those in the landscape whilst retaining a structural clarity that allows observed fact to become something pictured and true.

CBP: Looking at your paintings, they feel like the direct experience of moving through a landscape as a launch pad into the journey of making a painting. Can you talk about personal experiences that influence your painting?

SC: The work is entirely based on the experience of being in and moving through landscape. I live on the Essex coast, close by beaches and marshes, everything bounded and transected by seawalls. The seawalls are my routes into and through the landscape. I carry with me binoculars, an A4 block of paper and a few pencils. I make quick and rudimentary drawings. I intend to record what I see, or how I see what I see, but what really interests me is the gap that drawing opens up, the gap between the thing seen and how it is put on the paper.

CBP: There is a strong architectural feel to your paintings, with broken intercutting lines that evoke land contours or allude to scaffolding. Can you describe how you explore the use of line in your painting? And is there a fluid connection to the plein air drawing you undertake?

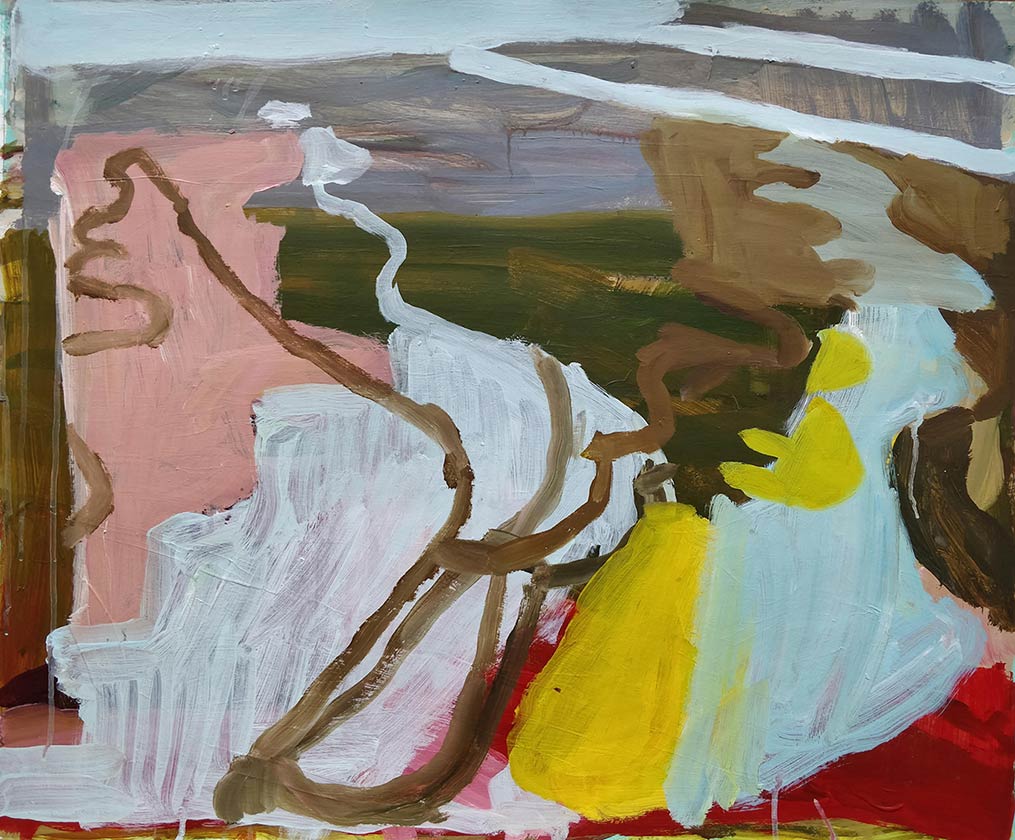

SC: The drawings I make outside are all marks and scratches and scribbles and lines, a lot of lines, and in the studio, they become the landscape I am working from. So the paintings are not just tutored by the activity of drawing, but are observations of actual drawings. Of course I know that certain marks were intended to express certain observations in the landscape but, in the studio, I think I see and use them primarily as marks. As the painting develops I am constantly returning to the same place in the landscape, making more drawings dictated by the demands of the painting. The process is some kind of dialogue between the act of painting and the experience of landscape mediated by drawing.

Broken Seawall I, acrylic on canvas, 30x30cm, 2022

Turning Back, acrylic on canvas, 70x70cm, 2022

CBP: There is also a varied and dynamic exploration of space across your painting, from the flat planes associated with one aspect of abstract painting, to a compelling sense of journeying through a painting, through corridors of painted structures and a convincing feel of perspective. Are you conscious of interpreting a range of perspectives and view points in the making of your work?

SC: I think I feel free to deploy all those marvellous things painting does, from making huge space to it being entirely on the surface. I like painting where you can see what has been going on; where resolution isn’t about tidying up. I like that play between the painting as surface and as space, when you can see the paint and then space inexplicably opens up. There is a balance, but I tend to favour the paint.

CBP: If you look at a sample of your painting, even over a recent short period, there is a close ranging approach to painting, yet a wide variation of characteristics from one painting to another. They are individually their own world. Can you describe something of the painting process for you that is about a constant discovery and not bottling how to do it, which keeps it fresh and engaging for you and the viewer?

SC: The longer you paint the more you find a voice or a way of working and you understand more of what you do. But I don’t really want to know too much about how to make my paintings. I would like to think I question and challenge my assumptions about what I make and how I do it.

The process might start by laying in a very rough ground of colour, relating to some colour observed on a recent walk, and then putting paint marks over the ground guided by a drawing. There is a lot of painting over or scraping out, revisions and second thoughts. Most of the process is about waiting for something to happen, or rather keeping painting in the hope that something will happen. I have ideas about what I would like the paintings to be like, or how I would like them to appear, but to some extent you have to accept what happens in the process. To work hard and then accept that these outcomes are yours.

CBP: How directly to you contain your colour palette from your landscape experience and reference points and how much do you play with colour with the tubes of paint in your studio?

SC: Colour is from the studio. Being out in the landscape your head fills with weather, light, temperature and sound as well as colour, and certain things persist and influence choices in the studio. So I do carry notions of colour in my head (and sometimes in notes or crayon drawings) and I used to think that that was were colour came from. Maybe it starts there, but in the long process of painting, colour is constantly being pushed around. So what started as a warm undertone might move from Burnt Sienna to Scarlet Lake to Cadmium Orange.

I am sometimes asked how I remember colours from the landscape; I don’t think I do, I invent them in the studio but work until they feel true.

CBP: If these are landscape paintings, they are predominately off square, or portrait shaped. If they are more of a landscape format, they are made of a diptych. Are you working with particular pictorial formats?

SC: I do tend to choose an off-square format for the paintings. Outside I draw on A4 paper, so a squarer format requires things to be shunted together and compressed, and I rather like that. It means I can’t just transfer information, it has to be thought about and reordered. The diptych does allow for a wider field of vision to be built in units, but what interests me more is the central dividing edge. Marks can move across the central edge or be interrupted by it, like turning your head to take in the landscape. That, and the conversation the two halves can have.

Walking in the landscape you are aware not only of what is ahead (the pictured view) but also where your next steps are going to be, and of things in peripheral vision, and a sense of what you is behind you, what you are walking out of. I would like to paint about all that.

CBP: The appearance of your paintings are fresh, spontaneous and often complex in how they are built up and the spaces and structures they depict. How do you know when a painting is finished? And generally how long do your paintings take to complete?

SC: At the moment I am making a lot of paintings on paper, around A1 or A0 size. These are made in layered stages, often working over abandoned earlier pieces, and may take a couple of weeks. The bigger canvases are worked on for much longer.

I try to be a bit off-hand in how the paint goes on, otherwise I know I have a tendency towards neatness. I am always guided by the drawings, and don’t take liberties with the topography, each painting being strongly connected to a location. But I’d like to think I am always pushing for something awkward and unexpected to happen. Finishing is problematic. For me It is something to do with resolving the painting problems within the work but not knowing quite how. Running through all the possibilities, then making it all work together with an unexpected move rather than by logic, so that the painting sings to you and continues to do so.

CBP: Aside from direct experience of a landscape, can you discuss some of the contextual references, painters and otherwise that inspire and influence your work?

SC: I look at a lot of different paintings, recently George Stubbs, Constable, John Crome, Veronese, Van Gogh, Emil Nolde watercolours, Graham Sutherland drawings, Per Kirkeby, Tal R, Roy Oxlade, de Kooning, Gillian Ayres and particularly John Walker. And the work of many my contemporaries, some of whose work I have bought or swapped over recent years on Instagram. It is a great joy and inspiration to have the work of my contemporaries around, telling me new things.

I programme exhibitions at a community space in my home town of Frinton-on-Sea (follow us @theartoffrinton) which I find really rewarding. It is a privilege to be able to offer exhibitions to artists and most enjoyable having their work in the town.

Apart from that I read, recently contemporary poetry, nature writing, bits of art writing, theology, some novelists. And garden – we have a good size garden at home and two allotments near the studio. They are gardened in quite a ragged, freehand way, a bit like the paintings.

About Simon Carter

Simon Carter is an artist and curator who was born in Chelmsford, Essex in 1961. He studied at Colchester Institute (1980-81) and then North East London Polytechnic (1981-84).

In 2013 he collaborated with artist Robert Priseman to form the artist led group Contemporary British Painting and then the ‘East Contemporary Art Collection’, the first dedicated collection of contemporary art for the East of England which is housed at the University of Suffolk, Ipswich.

Carter is President of Colchester Art Society and has been Artist-in-residence at the University of Essex and Firstsite, Colchester. He is represented by Messum’s.

Recent exhibitions include; 2022 Point-to-Point, Material Restlessness with Jevan Watkins Jones, Naze Tower, Essex. 2021 Shore Lines with Jevan Watkins Jones, Firstsite, Essex. Point-to-Point with Jevan Watkins Jones, Hamilton MAS, Suffolk. Messum’s Bury Street with Guy Taplin. Walking Home, Linden Hall Studio, Kent. 2020 Between Land and Sea, Messum’s, London. 2019 Made in Britain at the National Gallery of Poland, Gdansk and Contemporary British Painting at Yantai Art Museum, China.

Carter has work in collections including Ipswich Borough Council, Rugby Museum and Art Gallery, Swindon Museum and Art Gallery, Yale Centre for British Art, USA, Tianjin Academy of Fine Art, China, Yantai Art Museum, China and the University of Essex.