Lesley Bunch: Artist of the Month

Artist of the Month September 2023:

Lesley Bunch, selected and interviewed by Paul Newman for CBP.

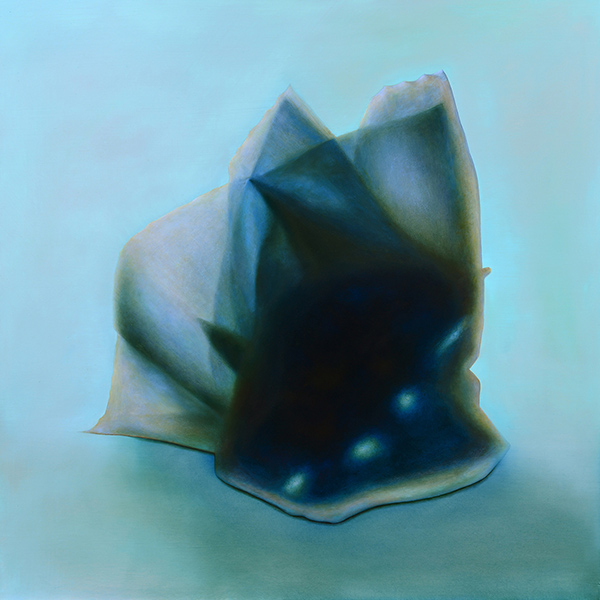

Lesley Bunch won the Contemporary British Painting Prize in 2022. Lesley talks about her enigmatic ‘Shadow Sculpture’ painting series which are based on the creation of shadows with ‘invested objects’ lent by other people.

Reproduced in my paintings, each shadow becomes a manifestation of, or ‘remains‘ of, my exchange with the lender…I am interested in the moment when the painting takes on a life of its own and seems to guide my hand; when the colour-sculpted presence takes on an expression of ‘suchness’, and becomes an intricately detailed, solid form…

CBP: This time last year you were announced winner of the 2022 CBP Painting Prize. How has this year been in terms of developments in your painting practice and projects?

Lesley Bunch: It has been transformative. It has raised awareness of my practice, resulted in further exhibitions and I’m thrilled that one of the paintings in the prize exhibition is now part of the Priseman Seabrook collection. It has been wonderful becoming a member of Paint Britain and getting to know the other painters.

With it came an invitation to be a selector for the prize this year. It has been a great privilege to have a close look at the diverse approach to painting from across the UK. Researching the work off judging platform at length, watching interviews and reading statements, seeing how the work had developed was fascinating, there is so much probing thought, philosophy and poetry inspiring the painting out there.

CBP: I was on the selection panel last year and I remember the distinctive first impression seeing your work online, it was unique and beguiling with a sinewy virtual quality. There is quite an involved process though, that’s not apparent when looking at these futuristic, sculptural paintings. Could you talk about the starting point for them?

LB: The starting point was my degree show work at Goldsmiths’ back in the early 90s. I had been admitted on the fine art / art history combined course with my paintings, but within the first year found myself a habitual resident of the darkroom, experimenting with photograms. The internet was in its infancy, there was no such thing as e-mail, a few prototype mobile phones were briefcase size. I became fascinated by the talk about ‘Cyberspace’, what was to come, what would ‘virtual reality’ look like? For my degree show I designed imaginary, never-to-be-made objects with no discernable function, using Cadkey. I subjected these ‘potential’ objects to multiple manufacturing tests using Moldflow’s new software that identified potential flaws in process and mould design for yet-to-be made injection-moulded plastic parts. I measured the effects of injection gate location, cooling rates, and alternative types of plastic; these tests resulted in a whole lot of diagnostic information-overload about something that didn’t, and would never exist.

I produced photograms using diverse found material to represent the objects. I overlaid these with photo-silkscreens on glass, containing the diagnostic information in the computer language of the time, printed in UV sensitive ink. Each of the 20 in the series ended up looking like a chaotic, holographic, bit of jarring, nauseating, glowing information overdose.

My journey back to painting took about 10 years. In this time I was developing some of the preoccupations further in different mediums. Increasingly I had the benefit of hindsight as to how the internet had actually changed our lives, as we became bombarded with a proliferation of images, the new visual language of our global mass consumer culture.

A full leap back to painting occurred after I undertook a residency at Wimbledon College of Arts. While there I put a call out. I asked others to bring me their invested objects, and talk to me about the emotions, memory and etc. they invested in that object. Often, with the object between us, there was an outpouring of emotion, it seemed the object became a catalyst for a release of buried memories that had been pivotal moments in the lender’s life. I was aware that lenders’ stories were mediated and interpreted through my own experience.

I then borrowed each object for a few weeks, and created shadows with it. The shadows were composed based on my interpretation of the lender’s story. I captured the most moving shadow composition, one that for me represented the essence of the lender’s story, in a photograph. The next step was to use the photograph as a starting point for a painting.

CBP: What further processes are involved in mediating the subject and its translation into paintings?

LB: I decided that the best way forward was to represent the shadow of the invested object as convincingly as I could as an actual object. I didn’t want to achieve this through the materiality of paint, but instead with colour. The challenge was to apply the paint in layers, as flatly as possible, as meticulously as possible, using colour, transparency of oil, and optical mixing to achieve the most sculpted, luminous effect I could; something akin to the flat, glowing computer screen, upon which we discern the virtual as real. It was important that the finished ‘shadow sculpture’ was detached from, and could not reveal its ‘casting’ object; similar to the way our relationship to our invested object is hidden, or when described, is mediated through the experience of the listener.

Knowing what cast the shadow isn’t the point. I believe that these invested objects have agency. By virtue of investing our memories in them they can become catalysts for change. We constantly reinterpret their value in light of the trajectory of our life experience. When they are rediscovered in our cupboard the memory invested in them might be a trigger to change a decision we make that day. I don’t believe they are of constant value to us. Therefore a title for each painting, or a label of any kind other than a number, seems wrong.

When I start painting, the initial sketch is fairly representative of the composed shadow. As the painting progresses some elements are exaggerated, some disappear. It becomes increasingly edgy and meticulous, gaining the quality of particularity, of ‘suchness’. All the while I keep the lender’s story in mind. They are some-thing, but changeable depending on the viewer and context in which they are seen.

CBP: When seeing your actual work on display you notice the painterly gestures even more. I remember thinking, they evoke something almost of Pre-Raphaelite paintings with their apparent close-knit brushwork, chromatic feel and luminosity. I’m not sure how helpful this is as a connection, it was just an instinctive thought. But there is feeling of looking back at painting histories as well as looking forward into the unknown with them. Do you reflect on historical painting or other cultural artefacts as reference points in the making of your work?

LB: In terms of how I apply paint, my method is similar that of the Pre-Raphaelites for my Shadow Sculpture paintings. However overall, it is difficult to name one historical movement, or a particular set of cultural artefacts as being dominant points of reference. A study of art history and theory stays with me, and I return to some paintings time and time again. At Goldsmiths’ I studied western art history, from the Renaissance to Postmodernism, and later at SOAS I studied archaeology. I concentrated on Japanese art of the Edo period, in particular Mitate-e in Ukiyoe, and spent a lot of time thinking about Japanese writing, in particular haikai and koans. This all has informed my approach, sometimes directly, sometimes indirectly.

CBP: Can you talk about your painting process, paint application and how you approach gesture in your paintings?

LB: For my Shadow Sculpture series I start with a sparsely applied, loose graphite under-drawing directly on the support, for delineation only. I do not do preparatory sketches. I mix mainly on the support, a smooth, most often white ground, but occasionally unprimed aluminium. Layers are scrubbed on with small brushes, with fine detailing to build structure. For areas that glow, I build up thin layers, mostly transparent, but with some opaque detail or gesture, in an instinctive, non-systematic way. Transparent areas act like an optical filter allowing light to pass through, and I avoid obscuring previous layers of colour. Light interacts with glazes in an interesting way, travelling within the painting’s surface and lighting them from behind. Instead of using mediums to achieve this I use the carrying oil in transparent hues to create the same effect. Layers don’t follow a consistent sequence from ground, under-painting, to finish. I juxtapose areas of intense glow with areas of darkness, which absorb light and create depth.

The final few layers unify the colour of light, control its intensity, highlight forms and elements to further create a sense of 3D space. It is at this stage that I get elements to respond to each other subtly, for example to get colour to reflect from one element to the next. I prefer to paint exclusively in natural light, or in winter months with lamps to simulate its colour.

For my Shadow Sculpture series, the background is approached differently. Here the paint is applied in a few layers, flatly with less sheen, but with a large brush. I preserve the one-directional brush marks. This helps to make the shadow sculpture stand out.

After each painting session, I move around the painting, checking the brush marks in raking light, making adjustments, and smoothing some areas with fan brushes. As the painting dries, I decide which areas need more oil-rich transparency to adjust sheen. This is challenging, as the painting takes a long time to fully dry, with sheen changing for months.

CBP: Colour is a key, heightened element in your work, which is about shadows, though explored more chromatically than tonally. The press release for your 2022 exhibition ‘Cut Two Pieces in Three’ describes you ‘sculpting in colour’ can you discuss your approach to colour in the translation of imagery, colour mixing and application in your paintings?

LB: I love the foggy penumbra of a shadow, within which a full range of hues seem to hang together, in layers, in 3 dimensions. This is exactly what I try to replicate through the layering in my paintings. A thick application of paint would mask this effect. It requires a barely-there application.

I use a wide, unrestricted palette of hues, both muted and intense, including modern organic hues such as quinacridone, phthalo, and napthol. I build layers in a multitude of hues, unifying them in the last few transparent layers.

I continually experiment with what colour needs to be next to or underneath another to get it to ‘glow’. I sometimes alternate complementary hues, again and again until the top layer optically mixes with all those below to create a shimmering effect.

Now, so many artists are wrestling with the proliferation of visual imagery in our screen-obsessed world, with its chromatic back-lit intensity. I try to reference this with the thinnest possible, scrubbed-on layers for a 2D, smooth finish.

However illusionistic the subject, the painting is ultimately an object. I consider the light in which a painting is seen as the final, mutable, layer of colour. I have often returned to Rothko’s Tate murals to appreciate his layering of subtle gesture, hue, sheen, and attention to the quality of light in which the final painting might be seen and moved around. I love his Tate murals, with their variety of materials used, oil–modified alkyd, various resins, egg and oil, in which he presents changeable, subtle surfaces by varying sheen, and relies on the movement of the viewer around the painting to reveal and hide.

CBP: What about control verses the unknown? There are a few clearly defined stages in translating your source imagery. Can you talk about the painterly discoveries you make on the journey and if there are still unexpected happenings closer to the end of the process of finishing a painting?

LB: Sometimes an accidental or exaggerated brushstroke from the initial loose rendition stands. It remains through the building of layers, but it is worked into, shaped, reshaped by subsequent layers. I love the moment when the painting talks back, when something exaggerated demands it remain present, and seems to guide my hand in painting the neighbouring elements.

As I near the end of a painting, the final few layers are the most difficult. How to bring all the elements together to make the object ‘believable’ as a 3D entity? This is where the most difficult experimentation comes into play, which colour sits on top, unifies the top layer, without losing the important detail below? The occasional exaggerated or accidental mark can change the direction of a painting. When it happens, the negotiation with it is what I love most when painting. To achieve a balance I have to grapple with how much it takes over. This can sometimes completely change the overall effect.

CBP: Virtual is a word that can be applied to your paintings in their sophisticated technological appearance, influenced by processes involved in their production and in terms of the other meaning of virtual; shadows and light and your interpretation of these elements. Could you discuss this notion in relation to your work?

LB: Shadows are a convenient vehicle for the ideas behind my work. They are a 3-D event, ‘a hole in light’, or a moving of light through or around objects, composed with the aid of a halogen bulb to exist for a short duration of time.

I portray the 2D trace as a 3D object, an illusion, sculpted with colour. I want to make them look like you could pick them up. This is partly achieved by an introduction of a hint of ground, by inventing another shadow cast by the shadow-object. Colour emanates and reflects from one element to the next. Neighbouring elements within each shadow cast shadows upon each other. To use colour to represent the movement of light in this way I activate a sense of touch, a sense that the shadow-objects exist in three dimensions.

A 3D shadow is not collectible. But to paint its trace is to make an object. My Shadow Sculpture paintings are numbered, serial, collectable but with an ‘absent final term’. In his System of Objects “A Marginal System: Collecting” Baudrillard wrote “what is possessed is always an object abstracted from its function and thus brought into relationship with the subject” and “what you really collect is always yourself”.

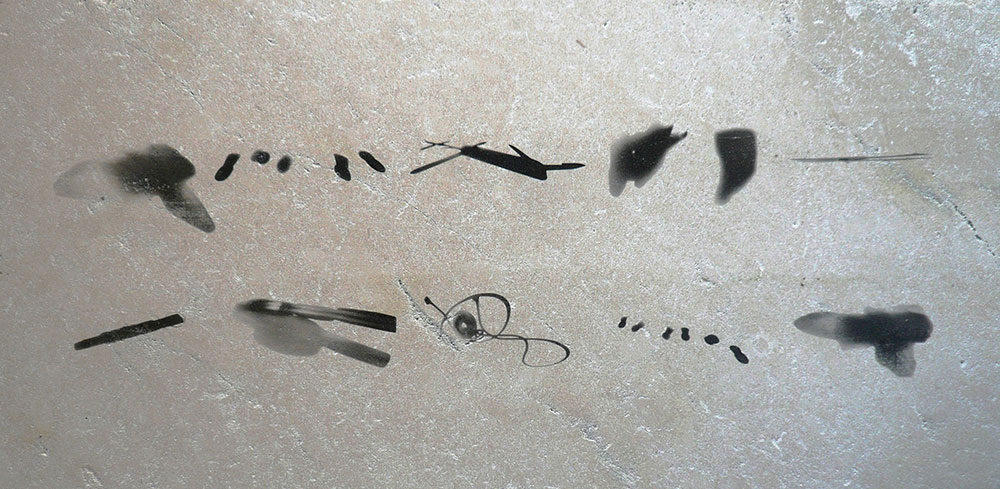

CBP: Your shadow paintings are about communication, with other people, their stories and objects during the initial stages and the translation and distortion of these into the final inscrutable objects made by you. Your paintings feel they are trying to communicate something with their clarity of form as an indefinable visual language. You also produced ‘Shadow Language’ a series of photo emulsion works incorporating imagery from ancient manuscripts. Can you talk about this series and more generally about language and communication as a thread throughout your work?

LB: To make sense of our surroundings, draw boundaries in our lives, and create a sense of control, we collect, classify, objectify, label, verbalise. Language shapes our experience and our relationships. To understand another’s experience we frame it within our own. I think of my Shadow Sculptures as manifestations of, or ‘remains’ of my verbal exchange with the object’s lender. They are my interpretation of lenders’ stories, framed within my own experience, and I remain wary of our limitations in translating and conveying others’ experience. These paintings remain in the space in-between. They defiantly remain a visual language, repelling verbalisation and labelling. Despite being presented as an object, each is infinitely reduced to itself, impenetrable, unclassifiable, de-familiarised form. We cannot position ourselves to the painted object. We cannot determine a value for human use, or ascertain the original function of the casting object. We cannot label it. We cannot therefore take ownership of it, and our predisposition to do so is thus laid bare.

In his Six Memos for the Millennium Italo Calvino said that “I think we are always hunting for something that is hidden or merely possible or hypothetical, something whose tracks we follow as we find them on the surface of the ground … Words connect the visible track to the invisible thing, the absent thing, the thing that is desired or feared, like a fragile makeshift bridge cast across the void. For this reason, the proper use of language, to me, is the one that helps us to approach things (present or absent) with discretion, attention, and caution, and with respect for what these things (present or absent) can tell us without words.”

In my Shadow Language series of photographs, I place these ‘remains’ together in the guise of logographs, so that the shadows resemble a sort of language.

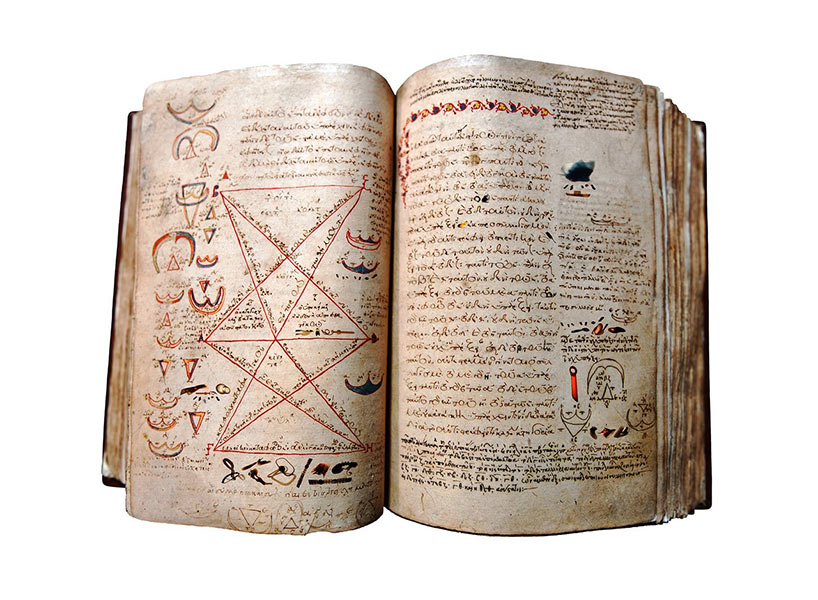

For an exhibition at the Biblioteca Angelica Rome in 2018, I made work in response to the library’s collection of manuscripts.

Many of the ancient manuscripts in the library contain lacunae within their pages. These were gaps left intentionally to allow subsequent owners, scholars, and researchers to add annotations.

I was allowed to photograph some manuscript pages containing these gaps and annotations, including a reproduction of Aristoteles, Opera (Biblioteca Angelica manoscritti greci, Ang. gr. 42 dated 1301-1400). Here Aristotle attempted to classify, and geometrically and mathematically define, an emotion. Comprehension of the shorthand Latin is lost to all but a few, its annotations and marginalia virtually indecipherable. For my photograph ‘Lacunae No. 3’ I digitally inserted Shadow Language annotations into the manuscript.

In the Lacunae project my Shadow Language is dependent on context, designed to absorb a multiplicity of meanings, coexisting in harmony. When the shadows are dropped in, no meaning is transferred in a fixed way from shadow to text, or text to shadow. Their placement may encourage a temporary transfer of meaning between the verbal and nonverbal, however any meaning assigned vanishes when the same shadows are encountered in a different text, from another historical era.

My intention was to reflect a plurality of experience, with an ‘effacement of the agent’. The focus not on something signified by language, but on the infinite meaning-generating potentiality of language, its focusing on and ever renewing itself.

Like my Shadow Sculpture paintings, my Shadow language remains a visual language, resisting fixed verbal interpretation. Both are something of the unanchored over-information that we increasingly drift in, here juxtaposed with lost language, thought and enquiry.

CBP: Describe a typical day, or session in your studio.

LB: A typical day starts with a walk to collect my thoughts. I often write a few ideas down in a diary before I start to paint, mainly thinking about what my next series of paintings will be, but also how to develop the current series.

I usually have 2-3 paintings in progress, as I wait for each layer to dry before applying the next. A perfect day is when I have a stretch of at least 6 hours ahead of me to paint.

Lesley Bunch is a painter and photographer who lives and works in London. Her work has been exhibited widely in the UK, Europe, Asia, South America, and the US.

Lesley was awarded the Contemporary British Painting Prize in 2022. She has exhibited in the UK, Europe, Asia, and the US, with solo shows ‘Absence : Presence’ in Rome, ‘Shadow Language’ in Seoul, and ‘Cut Two Pieces in Three’ in London.

Recent solo exhibitions; 2022 Cut Two Pieces in Three One Paved Court Gallery London,2020 Shadow Language CICA Museum, Seoul.

Recent group exhibitions include; 2023 Open Artspace, Old Parcels Office Scarborough, A Slash of Blue Gerald Moore Gallery, London, Fragility Unveiled Palazzo Pisani Revedin, Venice, Italy, X – Contemporary British Painting Newcastle Contemporary Art, Newcastle, Soliloquio Tempio di Pomona, Salerno, Italy. 2022 Contemporary British Painting Prize 2022, Artworks Open 2022 Barbican Arts Group Trust, London, Tapped 13 Manifest Gallery, Cincinnati, Ohio.

Essay by Hettie Judah for Contemporary British Painting Prize catalogue 2022

Write up for “Cut Two Pieces in Three’ of 2022 at One Paved Court in London