Leap Before you Look

An essay by Matthew Burrows about the work of Susan Absolon the winner of the CBP Prize 2021

This essay was published in the CBP Prize 2021 exhibition catalogue. The essay forms part of the prize.

‘A solitude ten thousand fathoms deep

Sustains the bed on which we lie…’

– W. H. Auden

In an age which worships speed in nanoseconds and a culture that expects immediate satisfaction, despite our acquiescence, the paintings of Susan Absolon may seem archaise. They quietly tip from the corporal to the metaphysical without pretension or need for explanation. And, whilst at first glance appearing abstract in form, they seem to bear a stark familiarity with ‘the gritty reality of everyday’. Is it the earthy colours and subdued light (the whites absorb as much as they reflect)? Or, is it their granular tactility, which owes more to the natural surfaces of linen, cotton duck, wood or even stone, than the now familiar digital aura of screens? Whatever it is (and perhaps we need not know), it isn’t a cloying nostalgia or need to be recognised as being like ‘this’ or ‘that’.

Absolon’s relationship with art started early. The daughter of a painter, she grew up ‘surrounded by paintings and books’ and formed her deeply personal relationship with art. Despite this she didn’t arrive at art school until her late twenties having turned down previous offers of a place. Before studying art at Farnham and Central St Martins Absolon had read Spanish and South American literature at University College London and has a keen eye for the ambiguities of language. Her paintings speak with the same layered epistemology, and it takes a little time to allow the surfaces folded in veiled areas of paint to work on the mind’s eye. These are paintings which cannot be rushed, their uncertainty must be lived with in a spirit of trust. ‘It took a long time to craft a language that enables’ she tells me. ‘Enables’- I kept reflecting on that word as it stuck in my teeth like a pip. It suggests a call to knowledge, or opportunity. Or perhaps opportunity that ‘enables’ knowledge.

Absolon’s paintings suggest a ‘drawing’ from ‘something’. They have solidity and form, perhaps organic, pertaining to a geology of some kind. There’s also time and space, a before and after, in front and behind. To look at them requires the eye to excavate the surface, picking at what might or might not be something that can or cannot be recognised and read. Their ambiguity sits between landscape and the forms revealed from erosion. It is an ancient topography. An uncultivated landscape, where the slow-time of earth’s natural cycles take centre stage with only the occasional suggestion of industrialisation.

If our familiar traditions of landscape painting had not existed, borne as they were out of industrial society, we might very well call Absolon’s paintings landscapes. But is this to evade the challenge of ‘looking’ that Absolon’s vision proposes? There’s a weight to the forms and a need to live with and reflect on the presence of their space and surface with the discreet hints of human presence. The dynamic between these qualities is where medium and shape find a coalescence which gives the viewer confidence to explore. Dugout, at 91 x 91cm a large painting by the artist’s usual standards, offers a space entangled in a web of drawn lines. The bottom two thirds of the painting feels earthbound and gives contrast to the dusky pinks at the top, held in place by a strip of ochre. The web breaks the certainty of theses familiar motifs linking the top and bottom of the painting. At times the pink and earthy pigments break into and dissect the authority of this web. It might suggest the stratification of geology or an internalised reality stitching itself together through our experience. Absolon explains that the title Dugout can refer to a two-chambered box for marijuana smoking, or to a command bunker or a shelter from enemy fire. These ambiguities enlarge our sense of reality as a complex interplay of advance and retreat, like the evolution of painting itself.

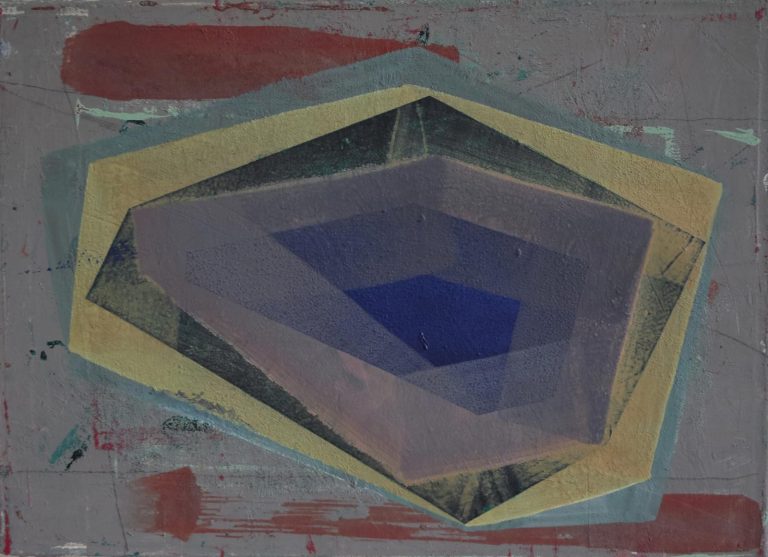

A liquid blue light fills the centre of a small painting titled Inflatable. It has a glow more akin to bioluminescence, a natural defence mechanism of marine creatures like phytoplankton, shrimp and squid. Its light seems to be emitted by its very nature rather than a source outside the painting. There is the hint of an external light in the background. It is faint, but acts to give prominence to the internal light of the blue shape forming within the painting’s darkness.

The painting, says Absolon, ‘is a motif of failure, a plump presence, weighed down by its buoyancy, with an inner light that fails to illuminate a dark place’. The title offers a playful ruse, a puzzle, not to be completed but to be pondered. If it is an ‘inflatable’ then it has seen better days, but is that my assumption that anything inflatable has to be driven by the ‘sleek perfection’ of industrialisation!?

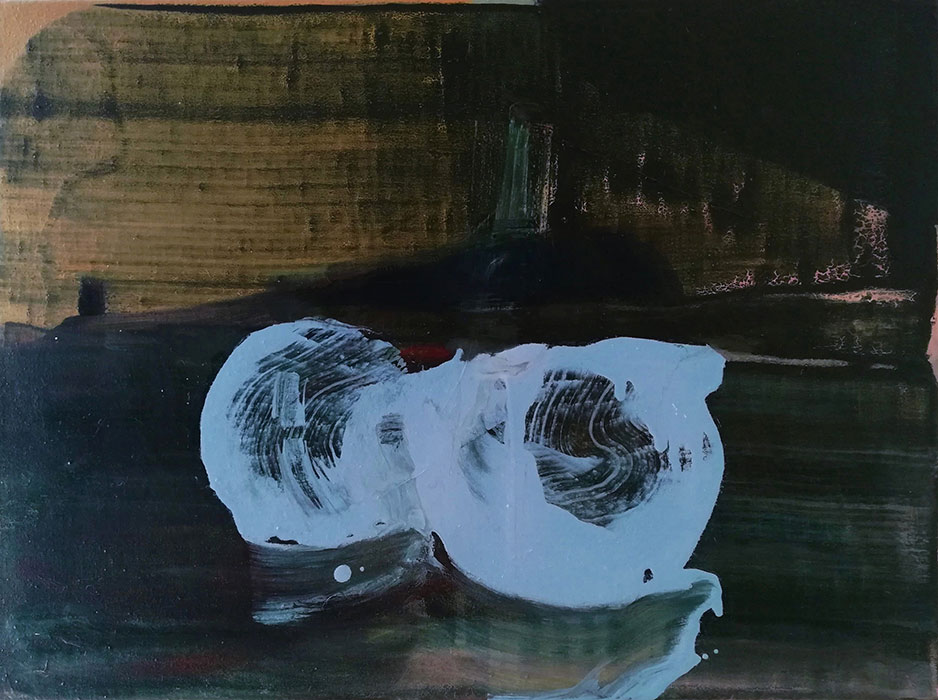

Ten Thousand Fathoms is the title of another small painting. Landscape in format yet split in two by a divide of light and shade. At first glance it seems to be a repeated motif on the left and right. But careful inspection shows only a familial relationship. We are pattern seekers, we look for relationships of type and regularity. It is the basis of language and our ability to ‘understand’. Breaks in these patterns draw our mind’s attention, it may be an evolutionary quirk that allows us to quickly spot danger lurking undercover, but it’s also the fulcrum around which the objective and subjective world pivots. ‘The gritty reality of everyday’ is so often stained with the hopes of our internal lives, hopes that have a real world impact. Absolon keeps a copy of ‘The List’ in her studio; which documents the 40,000 plus deaths of refugees and migrants due to European political policies: “its succinct narratives of finality always shock me” she says. This is a central paradox to this and many of Absolon’s paintings. At their heart is a need to see, to not turn away from reality, but towards it, whilst recognising the deep mystery of our internal narratives, stories we tell ourselves and others to give shape, form and colour to our imaginative universe. Absolon feels deeply about the horror of injustice, yet she does not tell you what to think, but patiently gives space for our minds to grasp its portent.

I was surprised to discover that Absolon does not draw – in the traditional sense – instead she finds creative sustenance in the opportunity that the first marks made on the painting’s surface give. Indeed they are not drawn from anything ‘seen’ and ‘observed’ but from a deep poetic reverie and the urge to ‘strike out’. They skirt close to being an image but resist the mundanity of recognition. Closure is not on the cards only a cyclical need to listen and bring forth into sight.

Ultimately any desire to see an illusion is just that, it’s a trick of language, a deception that allows a ‘reading’ of signs and symbols. The word symbol derives from ‘symbolon’ which means ‘to throw together’. It is always tempting to want a symbol to mean something specific, to have a definition which can neatly end any doubt about the mystery of things. Absolon repeatedly throws together, then patiently waits and listens.

Anyone familiar with the process of painting will know the discipline this waiting requires. There isn’t an end to it, it can be and often is tinged with despair, frustration and be weighted with self doubt. It takes a certain kind of faith to live with this, to allow its poetic reality to reveal itself when it is right to do so. We can all experience this at times, repeating it time and again demands a kind of painterly wisdom.

‘Leap Before you Look’ is the title of W.H. Auden’s poem from which the title is derived. Making that leap into the unknown is the alpha and omega of Absolon’s paintings. It is a slow-time, one tinged with melancholy, a time that is ‘A solitude ten thousand fathoms deep’. We all see the way the world ‘is’ from who and where we are. Absolon shares this experience trusting that we too may draw out of this ‘throwing together’ something like our reality too.

Matthew Burrows MBE