Selfish, Sticky & Successful

An essay by Beth Hughes (independent Curator and Researcher) about the work of Rich Jellyman the winner of the CBP Prize 2023.

This essay was published in the CBP Prize 2023 exhibition catalogue. The essay forms part of the prize.

‘Human creativity is a process of variation and recombination’

Susan J. Blackmore, The Meme Machine (1)

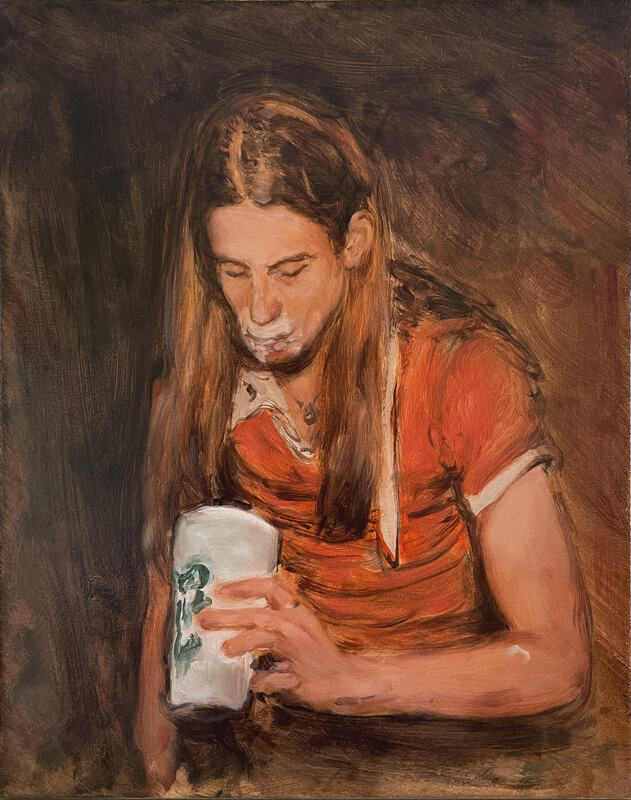

Rich Jellyman’s portraits catch the eye from a distance. A moment with Illusion (2022) splits the mind between its classical painterly style popular throughout portraiture painting and the distinctly contemporary feeling of the icky, visceral imagery; what is that on the subject’s face? The combination of defiance and absurdity in the Anthropomorph series of paintings is reminiscent of a popular form of internet selfie. For those of us saturated in the internet’s visual culture, the combination of something momentarily layered with humour and perhaps a touch of strangeness is all too familiar. Isn’t that the formula for a viral image?

When Professor Richard Dawkins coined the term ‘meme’ in his seminal 1976 book The Selfish Gene five years before the widely recognised birth of the internet, he described memetic theory in wider terms than our current usage, extending it to any cultural idea or behaviour that is imitated and replicated. He talks about the longitudinal travel of memes: those that develop into customs and traditions and maybe more akin to how genetic information passes from generation to generation, and those which travel horizontally more in the manner of a virus and are more short-lived. This could be anything from religious practices to popular dances, or accents to The Ice Bucket Challenge, but the key definition is that it must be imitated and replicated.

There are two visual sources for Jellyman’s paintings. Illusion is part of a series of works where the artist took the internet meme trend ‘chaotic nightclub photos’ a twitter feed which shares the wild energy of drunken, often degrading and humorous ‘flashbulb’ moments, as his starting point. The more recent Anthropomorph group cedes a level of control to AI (artificial intelligence) software whereby the artist inserts an instruction into the computer programme and the algorithmically generated image returned to him forms the basis for his painting. The works typify three key qualities reflected in memetic theory: they are all selfish, reflecting an obsession with the self in popular culture (but told with a sardonic side eye which is a key characteristic of internet-based imagery); they are sticky, in that they persist without being promoted, explained or nurtured, making them ripe for replication; and they are successful – yes, as finely executed paintings with an accomplished visual language, but also by harnessing the power of viral imagery and continuing the memetic desire for replication.

Unlike Dawkins’ original thesis which posits that memes mutate randomly and are then ‘successful’ based on Darwinian selection, internet memes involve an element of human intervention, of creativity, inserting an element of control and drawing on a vast and unseen bank of social referencing. By extracting the image from the screen, Jellyman is harnessing the potency that made the image successful enough to become viral in the first place. But what is that power that causes memes to become popular and replicate? Just to satisfy a want for humour is too simplistic and they certainly don’t fulfil a basic need. There is a small dopamine hit to be gained from a quick laugh and an even bigger one from hitting the zeitgeist sweet spot by authoring an image that takes on a life of its own. Moreover they are a way to connect with one other, a shorthand that expresses our universality and which forms a strand of cultural anthropology. True, they may signal diminishing attention spans and reflect the darker prejudicial parts of society2, but also a sense of global commonality and connectivity told through creativity, since the successful meme has no regard for geographical boundaries.

The surface of Jellyman’s paintings is perilous and energetic. There is a sense that, even with the source imagery in front of him, the image is being resolved through the process of painting. If you follow a brush stroke across the painting’s surface it seems uncertain of itself or where it may end. Whether we can see the face, or whether the figure wears a mask, there is an undeniable focus on human connection, told through the contrasting painterly styles of heightened detail around the head area, and a looser more abstract style at times blending clothing with background. The composition and palette of Illusion reaches for the earthy tones and sense of isolation in historical portraiture, such as Gwen John’s largely monochromatic Self Portrait from c.1900. Yet while John’s composition demands eye contact, our figure looks inwards, excluding the viewer in favour of the cup in hand, creating a perplexing mood in a painting which raises more questions than it answers. Jellyman’s style isn’t that of photorealism. He is not fulfilling the meme’s desire for near faithful replication, but by introducing expressive marks, the clear presence of paint and paintbrush is an ever-present reminder than this is representational. This visual language elevates the image from the internet, an over-saturated platform marked by temporality, to the public art gallery: a place of analogue permanence where decision-making is historicised, contributing to grander cultural timelines.

The artist evolved his engagement with memes to its next logical phenotype, AI image generation. From the Industrial Revolution and the computer Deep Blue beating Grand Master Gary Kasparov at chess 1997, to the recent writer’s strike in America, we have long feared that the machines will replace us. As I write a conference is taking place at Bletchley Park where Elon Musk has announced that, in time, AI will replace the need for us to work. We can’t ignore how promulgating this thought benefits Musk enormously, and I would redirect the reader to anthropologist Professor David Graeber’s book and lecture Bullshit Jobs for a searing analysis of the labour market in a capitalist society. And yet when it comes to artistic production, current developments suggest AI will always be one step behind, summarising contemporary thought and lacking the authenticity to create those outlying moments where we see true creativity flourish. The place AI technology will have in our futures is essentially unknown, but provides a fertile foundation which shimmers beneath the surface of Jellyman’s Anthropomorph series.

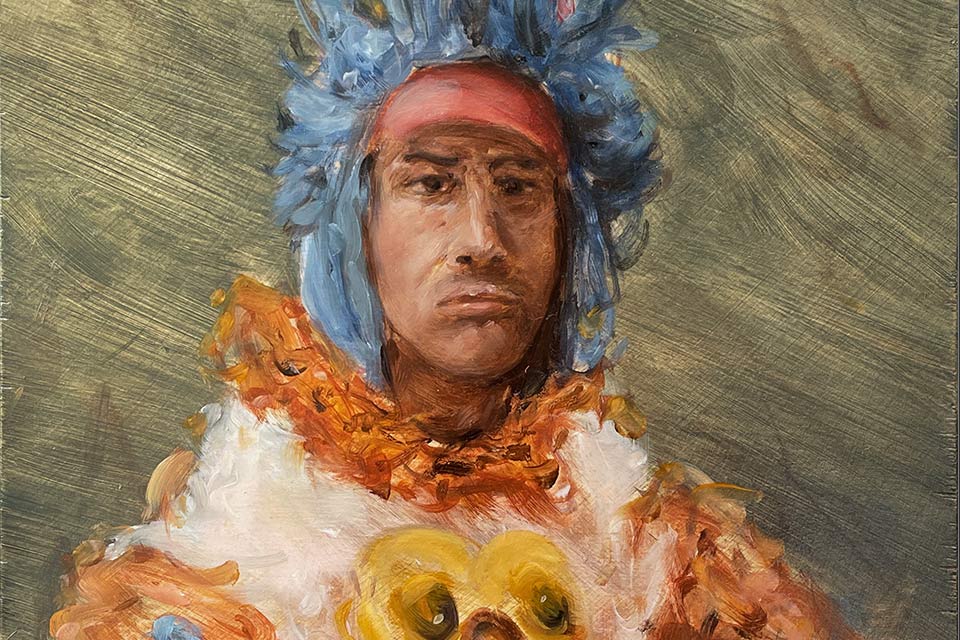

On seeing the two paintings from his recent Anthropomorph series I immediately thought of the raging mob that stormed the US Capitol on 5 January 2021 in the belief that Donald Trump had been robbed of the presidency, an idea that itself proves the effectiveness of memetic transference. The images of protestors glorifying in their animalistic and primal response echoes the upright posture of Anthropomorph (2), an Orwellian beast of capitalism complete with suit and tie. In Chicken (2) the mask has been dropped as a macabre beaked face hangs on his chest to reveal a pouting and scathing nonchalance, the kind of attitude which dares you to question how they choose to present themselves. Both images are sticky, they persist: by this I mean they are just bizarre enough to stand out but not so obtuse as to alienate; they are familiar enough to negate the need for explanation yet they raise questions; and their potential for re-framing and adaptation appears endless.

In the process of writing this essay I considered asking the artist for his source imagery and exactly what words he put into the AI bot. I even thought about presenting two texts side by side; one written by this fallible human lacking a proper grammar education and the second written by ChatGTP. However, in both instances I felt this would lead to shallow analysis, a trap of just comparing and contrasting where the focus on the paintings themselves would be sidelined. And besides, memetic theory teaches us that what has been replicated is not important, it is what is in front of you right now that captures your attention.

An artist’s power lies in the ability to concurrently reflect society and provide new perspectives on how to view and understand it. In Jellyman’s imagery he pinpoints the crossover between the potency of popular imagery and painting’s innate ability to introduce slowness and deliberation, where the internet image downplays human feeling as the screen forms a barrier. Painting reminds us of the warmth in humanity and the joy earned from realising creative potential. The internet meme undergoes an aggrandising process; an often-incidental image reframed and layered with new narrative becomes viral, and I suggest its end point is here. By reinventing the image in paint, the interjection of human creativity is central over and above what can be achieved in the world of technological advancement as this branch of repetition reaches its fruition in Jellyman’s expression.

NB: the writer is indebted to the artist, John Walter, for his generosity in sharing his insights on post-internet art, memetic theory and its application in visual culture.

1 Blackmore, Susan J., The Meme Machine, Oxford University Press, Oxford (England), 1999 p.15.

2 Researchers from Cornell University found that the vast majority of viral memes originated in more toxic areas of the internet such as subreddit and 4Chan. Zannettou, S., et al, 2018, October. On the origins of memes by means of fringe web communities. In Proceedings of the internet measurement conference 2018 (pp. 188-202).