Barbara Howey: Artist of the Month

Artist of the Month March 2025:

Barbara Howey, selected and interviewed by Paul Newman for CBP.

“My current body of work is paintings based on plants. Part of my process is photographing the species of plants seen on my daily walks, not rare but local, some native and some finding a space to grow where seeds have blown them from suburban gardens and wastelands… Painting nature has renewed relevance today in the light of climate change and biodiversity loss. My work references plants but also reimagines them through the process of gestural marks and heightened colour to create a space which slides between representation and abstraction and back again… Whilst the references are strongly related to the observable plant world the work is just as much about self-expression and the nature of painting itself.“

CBP: Your paintings depict plants and foliage, in medium to close up, sometimes they appear arranged. They feel moist and natural, a result of the paint application and like the entanglement of local fauna as experienced when walking. Can you discuss the starting point for this body of work, whether walking, photographing or drawing, and taking samples back to the studio. How did the series evolve from your earlier work?

BH: The starting point for my recent work is definitely walking. They came about after not making paintings for about a year and then lockdown happened. It was March 2020 and it was a joy to get out for the stipulated hour to enjoy the local woodlands and marshes where I live in Norfolk. I think the walks were heightened by the tragedy of Covid and being confined to your home, and because there were no cars on the roads the air detoxified and there was a clarity to everything. I took my mobile phone and started to document the plants on my walks. I then found myself back in the studio making paintings again. I like your observation about them being moist and entangled. The lushness and vitality along with the decay and the falling apart is part of the experience of walking through the landscape and is certainly what I hope to communicate.

The work I was making previously focused on damaged landscape of fracking sites taken from found images on the internet. Mostly they were aerial views. I really loved the work of Carol Rhodes, her landscapes at once specific and yet imagined. I think I moved away from this as I had to rely on found images and my thinking had moved towards exploring something more personal, my own locale and my own direct experience of being in the landscape.

CBP: When you’re in the studio how do you begin a painting? What sources do you have on your studio wall or in your memory and imagination?

BH: In this series I begin to work directly on a primed gesso board. I don’t do preliminary sketches but work my ideas out through the painting process. I have to hand a projector with images of the plants I have taken on my walks and photocopies lying around in the studio. I mix up a ground in one colour with linseed oil and white spirit and lay it over the surface. The paint quality has to be right and I mostly do this by the feel of it beneath the brush. I then work into the surface with colour and white spirit, marking and removing. The white spirit erases and introduces chance elements into the process but is also important to the meaning making. Erasure and loss of the image is important in what I want to communicate. I sometimes superimpose images or work from a photocopy of the plants and then usually I erase everything and start again re-laying the ground but with the knowledge I gained from the previous attempts. I then work into the surface in a freer way not relying so much on images but on a kind of urgency of movement, memory and improvisation. This may happen over and over during the course of a few days until something of interest with a freshness starts to appear and then it is usually quite a quick move to resolve the work. And finally, a decision on whether I can live with the results. If not, it all comes off and I start again.

CBP: The fluidity you achieve feels like its obtained through wet on wet and erasure of paint. Can you talk about your painting process. How many sessions and how long do they generally take to complete?

BH: Yes the fluidity of movement is really important and comes from using the wet on wet technique. This way of working evolved because of the subject matter and the intense and vibrant results it produces. Sometimes the work is quite quick and sometimes takes a few days. If it is a few days the extra pressure of finishing when all seems lost can be productive. I stay with the work all day maybe a few days until the work is done or has to come off. Sometimes I lose good paintings this way and keep ones that could do with more work but that is the hazards of working wet in wet.

CBP: How much of a high wire act are your paintings in terms of success or failure, do they mostly resolve themselves?

BH: The wet in wet process as you say is to some extent a “high-wire act” where you do need a certain nerve and commitment to each move of finger or brush mark as the painting can so easily dissolve into meaninglessness. It’s not so much a linear process but more like a rollercoaster ride where you get on one end and you experience great highs and lows and if you get off at the end ok there is a certain exhilaration in that you feel you may have pulled it off, but of course you could have just fallen off your wire and crashed to the ground. There are many “failures” or what I would prefer to think of more in terms of a thinking/making process in which you are learning how to make a new painting each time. This involves different ways of working to open up different possible resolutions/meanings. The paintings have to find their own way and shape. I am never quite sure when something is worth keeping. I usually photograph the work as it proceeds to get a more objective look at what is going on, maybe 3 or 4 times during the making.

CBP: You talk about nature as your subject and the nature of painting itself and as a material. I remember in my own conversation referring to ‘paintscapes’. Can you talk about notions of nature in your painting?

BH: I love this term “paintscapes”. This is precisely as it should be, the focus on the artifice of the painted surface. Painting has so many elements, its history, stuffness, wetness, fluidity, gesture, imagination, feeling and colour. This term brings to mind my favourite “paintscape” painters, Turner, Paul Nash, Samuel Palmer, Van Gogh, Munch. The Paintscape/landscape has so much meaning piled into it. Our longing for it, the loss of it, the anguish and delight. It can be a place of fantasy or document, idyll, repose, terror or the sublime. In this recent work my concerns are nature’s vitality, exuberance and at the same time fragility. The rate of biodiversity loss due to climate collapse is terrifying. My work seeks to put plants centre stage as a subject that is important. The painting acts as a repository for all these complex feelings about the non-human world. I don’t really see “nature” as separate from human species as we are all part of “nature”, but the painted picture is certainly a human and deeply subjective construct of the world and a reflection of the times and attitudes in which they are made.

CBP: Some of these compositions like ‘Late Summer with Reed Mace’ feel they are inspired by a periphery vision of overgrown flora beside or in front of you while walking. ‘Buried’ feels like it’s based on something cut and arranged and ‘Marsh’ like it’s conjured during the painting process as an abstract composition. How do you compose your paintings?

BH: As I mentioned earlier the painting have to find their own form. I don’t establish a composition in the first instance. Each piece has a different inflection to it. I had been trying to paint reed mace for a while but I think the combination of colour and the chance movement of the white spirit caused something unexpected which I liked, something about the cobwebby fluffiness when the seeds start to emerge. I like your thought about looking from the edge, things caught in your peripheral vision, indirect and slightly unnerving

The painting Buried is different from my other work. It is larger and it was based not on my own photographs but one I found on the internet and unlike my other paintings about plant aliveness this one is all about death. Plants are used here in their thousands, cut for their blooms on an industrial scale as flower tributes for funerals, marriages and love tokens. The image in the photograph was from a huge mound of flower tributes which covered part of a street in memory of the Russian dissident Alexei Navalny who died in suspicious circumstances in prison. I think this tapped into my horror about what is happening on a global scale. The wars, genocide, starvation and ecocide which are all interconnected through our obsession with exploitation of all kinds for profits’ sake. I don’t know really how to process all of this whole-scale destruction but the huge flower pile seemed to me to express something of the mass grief that is all around us which is seeking to find a form of expression.

Marsh-late September happened in an improvisational way which moved around between abstraction, expressionism and the decorative and which found an odd resolution which puzzled me and which I am still trying to work out. As a way into this work I think how other people see your work can be revealing. For example, someone commented on it on Instagram and said it was Rackhamesque which caught me by surprise and I really had to think about why there was a sense of recognition by me in this observation. Looking again at all those landscape and weird fairy illustrations I could see the point. I remember now as a child I loved those fantastical illustrations for Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. In Rackham’s work there seems to be a response to landscape which is unknowable, which could be described visually as magical or fantastical albeit in a strange English Edwardian way that references fairies and goblins and human/animal mix-ups but which also has echoes in so much writing that is specifically English from Shakespeare’s Midsummer Night’s Dream to The Wind in the Willows and Tolkien.

On a more contemporary note. The magical and fantastical worlds that are created by the anime of Studio Ghibli I am really drawn to. Its beautiful hand drawn landscapes familiar yet very strange with a marvellous mix up of animal/human invention.Whilst the appalling knowledge of nuclear holocaust always sits around its edges. I also love the magical “paintscapes” of Mimei Thompson and Gwang soo Park.

I am reading a book at the moment by Stephano Mancuso called “Brilliant Green” – The Surprising History and Science of Plant Intelligence” which argues that human understanding of plants is incredibly narrow. This is because they function on a different timescale we cannot as humans always comprehend, that is, very slowly. He argues that plants are much more autonomous than we know. They move, respond to their environment have modes of defence and attack, have senses, produce their own energy, produce oxygen and have connections to other plants through fungal mycorrhizal connections. Plants created the world we live in and get on very well without us but we on the other hand will die without them – no air, no food, no clothing, no medicine. I think maybe this aliveness and unknowability and power of plants over our lives could be called “magic”. Or as the Oxford English dictionary defines it as “an extraordinary power or influence seemingly from a supernatural source.”

CBP: Your paintings are mainly portrait format, which links to notions of cropping, historical floral still life painting and perhaps the phone as a documenting device. Can you talk about why you focus on this format for your painting?

BH: My paintings generally focus on one plant, you could say like plant portraits within their local habitat. The plants are usually tightly cropped when I document them with my mobile phone. Many of the native species are very small and delicate and you need to get in really close to see the detail and this has clearly influenced the format of the painting. There is the whole tradition of cropping in modernist painting since the invention of the camera and has had a huge influence on painting since. Degas of course, and Georgia O’Keefe’s tight cropped flower paintings spring to mind. I like the constraints of the crop as the experience of nature can be overwhelming and it works well as a way of composing a photo which doesn’t always feed back into the paintings but in many instances does. I am interested in the life that goes on around and beyond where the image has been cropped. I wouldn’t be interested in composing a formal still life of flowers in a vase as the 17th century Dutch flower painters did. Their work reflects the desires of their collectors and patrons and many of them are about the conspicuous display of wealth and the arraying of it as a spectacle to be consumed. In my work I hope to convey the vitality and life of more ordinary plants like thistles, reed mace and fungi and most of my paintings are relatively small.

CBP: I sense an underlying tone to your painting with its richness to 16th Century European still life painting and in a painting like ‘Day After Tomorrow’ and its feel of a vista, European landscape painting from the period. This is subjective, though can you talk about some of your direct and indirect references for your paintings?

BH: I get the richness references to 16th Century Still Life with its abundance and glossy intensity of paint application. But many still-lives of this time were inanimate, of dead animals, cut flowers, vases – so many luxury objects – and this is where my work departs as I wish to present an aliveness. There are always exceptions of course; for example the wonderful piece by Albrecht Durer, Great Piece of Turf (1503) which is truly alive and part of a growing world. I actually admire and identify more with historical Korean, Chinese and Japanese flower and insect painting; their lightness of touch, subtlety and exquisite line.

In relation to my references this is a really interesting question and one I can’t give a definitive answer to. As painters we spend a lot of our time looking at paintings by other people (at least I do). Over the years there must be so much enquiry and close looking gone into the work of others that somehow all those ways of making and reflecting on them and enjoying them in a visceral way become lodged somewhere in your psyche. At some level your preferences as a painter become informed by all that looking and not necessarily in a direct way. Yes I can really see 16th Century Flower Painting in some of the paintings and odd vistas in The Day After Tomorrow which may reflect my love of early Italian painting and East Asian flower painting.

This was the first large painting I made in this series and I didn’t know how to handle it. I used my same starting points but the paint handled so differently to my other paintings especially with the white spirit and because the surface was linen and not board. This is one painting I can say I really enjoyed making. I don’t know what was going to happen and this odd vista came about not in a deliberate way initially but by responding to what appeared on the surface how the paint had left traces. Then I brought in the plant which created a sense of depth to the piece. A view if you like.

The openness of paintings and impossibility of fixing one meaning onto them is what gives painting its power and gives each person their own way into a painting. Embedded in all paintings is their history and so there are bound to be multiple reference points and of course what knowledge and engagement the spectator brings to the works.

CBP: I remember when doing my A level Art in about 1992 being taken to the Warwick Arts Centre to an exhibition by Michael Porter ‘Close to the Ground’. I also love Graham Sutherlands abstractions of undergrowth. The late Dr Judith Tucker produced her Humberston Fitties series of dilapidated costal homes alongside the Dark Marsh paintings of the salt marsh plants from the area. How do you identify with these artists and the notion of close to the ground?

BH: I don’t know if I identify with these artists as I was not aware of the work of Michael Porter or much of the work of Graham Sutherland but it is good to be introduced to works I don’t know about. I really like the idea of “Close to the Ground” and looking at Porter’s work there is certainly a love for his subject which many times is quite humble. His series of path side paintings and his “Death of Nature” series are quite resonant and his paintings of dirt on paper are really lovely and certainly rings-true of my interests and I think of Judith Tucker’s “Dark Marsh” series. Looking at Sutherland’s quickness and lightness of marks and love of bugs and tree roots and the English landscape reminds me a bit of Paul Nash who is one of my favourite painters, but I don’t think I can make any informed reflections until I see the work for real and not digitally which are of course two totally different things.

I had also around this time, before lockdown, been walking with some botanist friends as we were involved in documenting a threatened habitat in a Citizens’ Science Project. It was fascinating going out with botany books and lenses exploring the minutiae of local flora and trying to identify and record all the species we came across, our noses in books and plants, and kneeling for hours in the different weatherscapes of the Norfolk Marshes.

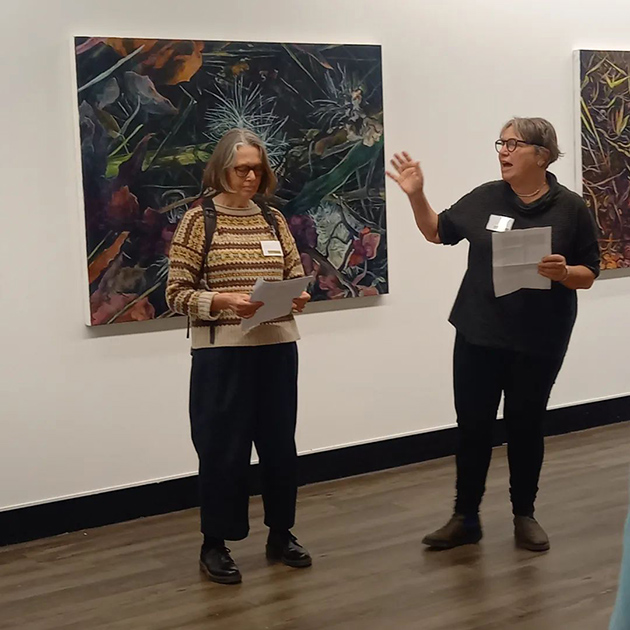

CBP: You have an upcoming exhibition ‘Plant Power’ at Groundwork Gallery that originated from an idea with Judith Tucker before she passed and will feature some of her final paintings. How did this dialogue and project originate, and what will feature in the exhibition?

BH: Plant Power had its origins in an exhibition that Judy and I curated with Grant Scanlan of Huddersfield Art Gallery called Entwined-Plants in Contemporary Painting, 2022-2023. We were looking for venues for a tour and we sent a proposal to Groundwork Gallery. We both really liked the focus of Groundwork which looks at art in relation to the Environment, which is a unique take for a gallery. We also wanted to broaden the artists participating to include non-painters. Veronica Sekules, the owner of the gallery, was very open to working collaboratively with us and brought a vast knowledge of artists working on Environmental themes and a whole range of artists working across media to the discussion. Artists included in the exhibition work in installation, video, sculpture, collage as well as painting. Judy was working on some large pieces for the exhibition before she died and it will be a great privilege to be able to feature them.

Barbara Howey’s first degree was in painting at Leicester Polytechnic in 1991. She then studied for an MA in Feminism in the Visual Arts at Leeds University in 1992. She completed a practice-based PhD in 2001 at Norwich University of the Arts. She has shown Nationally and Internationally and has had work featured in The John Moores Painting Prize. She also co-edited a volume of “Journal of Contemporary Painting” called “Commitment in Painting” in 2017 with Molly Thomson. In 2023 she co-curated a touring exhibition with Dr Judith Tucker called “Entwined – Plants in Contemporary Painting”. In 2025 the collaboration with the late Dr Tucker will result in a cross disciplinary exhibition at Groundwork Gallery called “Plant Power”.

Forthcoming exhibition; ‘Plant Power’ with Dr Judith Tucker at Groundwork Gallery, March 2025

www.groundworkgallery.com/exhibition/plant-power

Recent exhibitions include; 2023 ‘Arcadia for All?’ Contemporary British Landscape Painting, The Stanley and Audrey Burton Gallery, University of Leeds, ‘Entwined – Plants in Contemporary Painting’, Huddersfield Art Gallery, 2023, ‘Paint Edgy’, The Ropewalk Barton Upon Humber, Paradoxes, Contemporary British Painting, Quay Arts, Isle of Wight, 2022.

https://barbara-howey.co.uk/

Instagram: @howey.barbara