Abigail Hampsey: Artist of the Month

Artist of the Month September 2024:

Abigail Hampsey, selected and interviewed by Paul Newman for CBP.

Abigail Hampsey’s practice is interested in the overall exploration of landscape. Landscapes of the mind, of narrative and of the world around her. Now once again living in the landscape of her youth, the artist is for the first time painting these landscapes, not from memory as before but firsthand. Such paintings are conceived during long walks and runs into the unfolding fields and fells that surround her. Documenting what she sees with drawings, writing and photography almost obsessively.

CBP: On first encounter of your paintings, they trigger a sense of suburban, rural and autobiographical. Can you introduce the themes of your work?

AH: I think my work or my perspective rather is best described as being somewhere in the middle. In between places, spaces and times.

I live on the green belt just outside of Lancaster in the Northwest of the England, on the edge of the topographical line that separates suburban sprawl from rural, agricultural and wild spaces. Living in this middle place, I grew up with one foot in the fields one foot in the town. Or as I saw it one foot in a world of story and wonder and the other in a built up reality. As well as this, I spent a good chunk of my childhood accompanied by my grandparents walking and wandering the fields and fells that surrounded our home. During such times they told us stories of the landscape, its myths and their memories within it. It is these experiences and stories that the bases for almost all my work and the way in which I think about it, is derived.

My work sits in the middle of the factual and the fictional, the observable, the imagined and the remembered. Although the locations within my work more often than not depict the landscapes of the Northwest and Cumbria, the work aims to speak to a larger feeling of loss and almost a desperation for the need of preservation. A feeling I feel is echoed across the country perhaps even globally. This being the loss of our wild spaces, rural cultures and communities, trades, crafts and traditions. My work therefore aims to document these places pictorially, sculpturally or in any way I see fit, in an attempt to preserve them for the future.

CBP: There’s a sense of personal encounter in your work, depicting the self-portrait in relation other people and an environment. Can you discuss approaches to the portrait and autobiography in more detail?

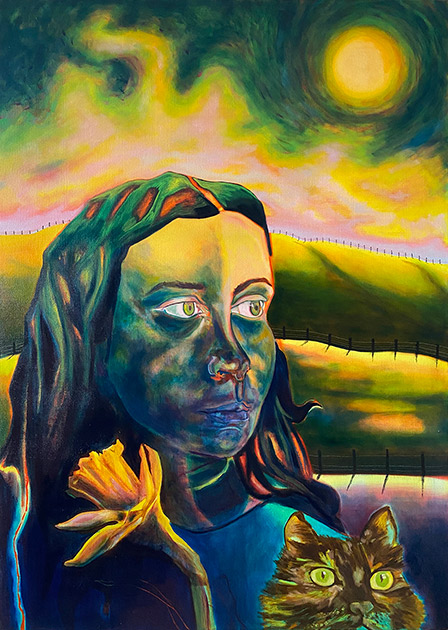

AH: In the case of ‘Self Portrait with a daffodil and Marcel’ this is in fact the first serious painted self-portrait I’ve ever done. My work is extremely autobiographical just in other ways. With studio time often hard won I try to allow my everyday to seep into the studio as much as I can, be that in the form of bread as a material due to working as a baker, the motif of moving legs as I like to run a lot or the mixing of porridge oats into my paint as I eat them everyday. Yet this is the first time I have pictorially memorialised myself. And I do see this painting as that, a sort of memento mori. I hold a Narcissus, a member of the daffodil family as a nod not only to the idea of depicting or obsessively observing oneself (as in a portrait) but also because it was spring when I was making this painting and so autobiographically it references the time of year this painting was made. As well as perhaps a small nod to the Wordsworth’s Poem Daffodils as some of the work in this wider body was made in the lake district, what we would call Wordsworth country.

The landscape behind me however is not in the lake district and is rather a depiction of some agricultural fields behind my grandparent’s house in which I spent a lot of my childhood playing and wandering. Unfortunately, these fields are due to be developed into new housing, thus forcing the suburban sprawl outwards and the once rural homes and places further inward. Consumed by development and expansion. This is why I see this painting as more of a memento mori, a comment on the death of a landscape and myself as some sort of custodian, or witness who is powerless to stop it.

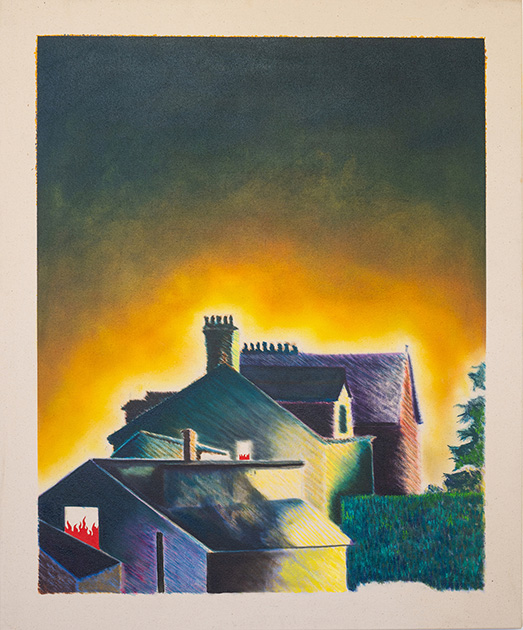

CBP: Can you talk about the depiction of suburbia in your work and the stark graphic motif of an open fire within the houses?

AH: I’m not sure If I ever really consciously think about suburbia although I suppose that’s where I now live. The house motif or the series of quite graphic houses I think came from a much more urban experience of living in London during my MA. I’d never been in such a large, continuously expanding landscape of houses before, it just went on and on and on. And being someone who as I’ve said is so reactive to my environment and referential to it, I just started depicting these houses.

The reduction of these houses into flat shape, colour and outline made them easily repeatable and so I could make a lot of them in varying sizes amassing my own city even. At the same time however, I was thinking about all the houses that were soon to be built back home and how this almost copy and paste construction of homes felt overwhelming. Yet as always in my work there are two conversations happening at the same time. The feeling of being swamped by thoughts of sprawling urban landscapes whilst also longing for a place for myself, a home or ‘A room of one’s own’.

I was projecting my desire to feel settled and safe. On late night bike rides home from work I would look into people’s glowing windows and imagine warm fires and home furnishings. The fire motif was then born as a way to depict feelings of loss and destruction as well as warmth and safety. These things, the house or the fire I often depict so graphically because they are so recognisable yet so individual in terms of meaning for a viewer that there is no need to embellish them, they are already inherently full of a history or experience that the audience will project and read what they want for themselves. I see them as icons or symbols when depicted so starkly. Culturally and globally recognisable.

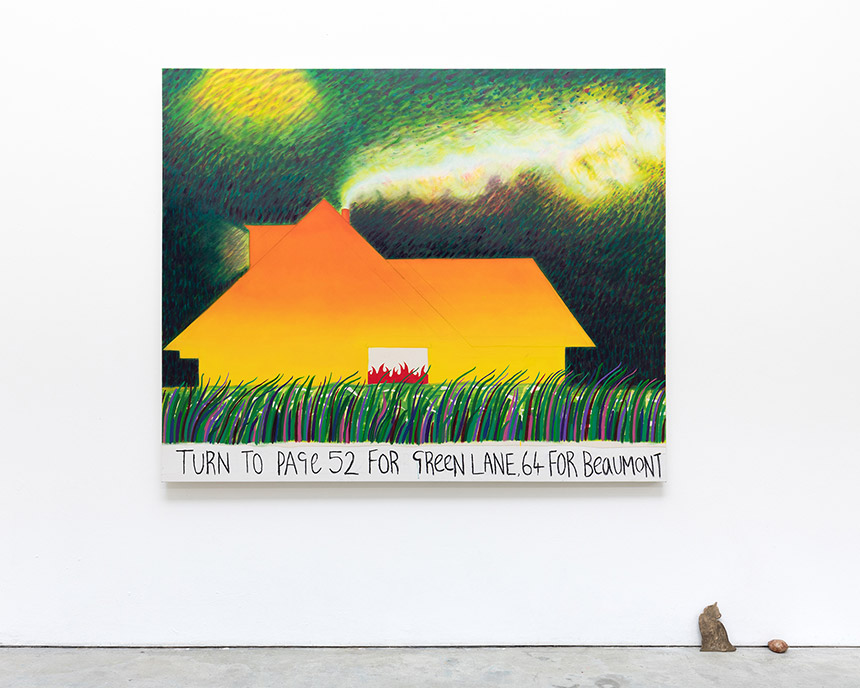

CBP: In this group of work, there is a painting called ‘In Your Mothers Name’ with text ‘Turn to page 52…’ along the bottom of the painting. Can you reveal more about this painting and your use of text in your work.

AH: So text isn’t something that I often use in my work, although it is something I am interested in exploring more. I suppose this is one of the only examples in which I use it.

During the time when I was making this painting I was looking a lot at the cross overs between the way we explore physical landscapes, or real places and the way in which we explore fictional or remembered landscapes through written narratives. My thoughts were that whether on a walk through a landscape or whether on a narrative path we don’t often have the ability to wander, to allow our intuition to guide us, paths are often if not always laid out for us and stories are already written before we get to the end.

So when trying to think of times in which we are allowed to choose our own path I was reintroduced to the books of my youth, that being, the ‘Choose your own adventure’ stories. Choose your own adventure was a writing framework that gave you a choice at the end of every chapter based on what they had just read, about where they wanted to go next for example, A: Continue down the winding path to the smoke in the distance or B: Go with the knight… or something like that.

I felt that in this way myself as the reader gained back some sort of autonomy over my destination or at the very least could follow my own intuition. So in reference to the text in the painting ‘In your mother’s name’ I was trying to give the viewer some kind of autonomy as to where they might like to go next when exploring the rest of the work in that show. Allowing them to make narrative leaps between the work and explore the space for themselves.

Second to this, the house depicted within this painting is in fact my grandparent’s house. They live on Aysgarth Road, Aysgarth is the maiden name of my great uncle Walter’s mother who worked for a house building firm in the 1950/60’s and who built his own home on this spot, naming the street after his mother. Hence ‘In Your Mothers Name’.

CBP: There is a drawing quality to your paintings, the brush marks and feel for colour sometimes evoke intense crayon work. Can you comment on this and what role drawing has in your painting?

AH: Drawing for me is like trying to remember your first words. I can’t remember when I first spoke but I have been speaking ever since. I don’t remember when I first picked up a pencil but… In so far as to say, I love drawing. It’s the thing that makes the most sense to me, that I feel the most confident doing and it’s the way I think through everything.

When it comes to the way I paint I suppose it’s just a similar thought process of layering and the drawn line, it’s the same hand so it would make sense that the output is similar. When I was still getting to grips with oil paint, how long they took to dry, figuring out transparencies and glazes and most of all how to layer them, it was colouring pencils that helped me with that. Pencils don’t need drying time or anytime really between one mark and the next and so you can figure things out much quicker, they can be thick, thin, hard soft, layered and block. Just like paint. And so they are one of my most used tools.

I carry a full set of colouring pencils and a sketchbook with me pretty much everywhere I go. There are worse habits.

CBP: There is a lyrical quality to your painting matched by your evocative titles. How do you choose a title for your paintings?

AH: I’ve always seen titles for works as either immediate or sort of hap hazard. They either allude to some kind of liminal no man’s land of narrative or myth or they simply describe the work. So ‘Self Portrait with a Daffodil and Marcel’ is purely descriptive whereas ‘In Your Mothers Name’ is a little more vague. I think titles can also be an opportunity to almost leave Easter eggs or hints to the viewer about what you were thinking about or what you were looking at while making the work.

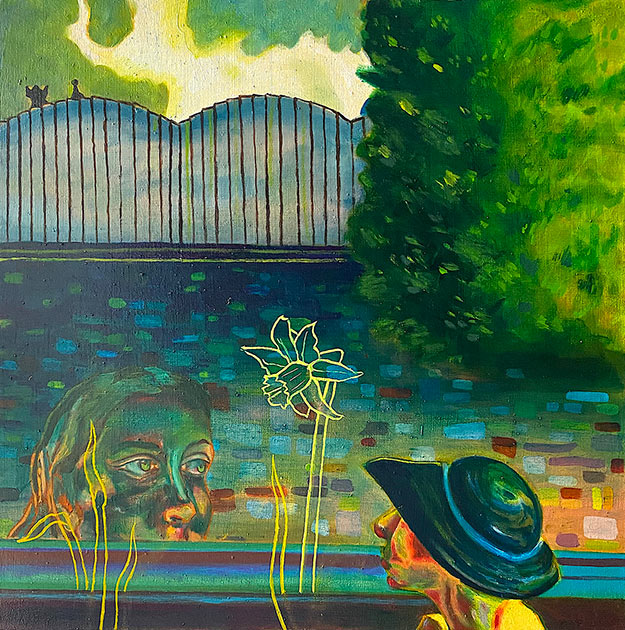

‘An Allegory of life and time’ for example partially references the painting ‘An Allegory of Truth and Time (1584–85) by Annibale Carracci’. I just swapped the ‘truth’ for ‘life’. I was looking at this painting a lot while making this work and even visually referenced it too.

I do have a keen interest in language as a whole whether poetry, semiotics or dialect words, so perhaps I’m trying to explore the more descriptive poetics of language through my titles as well.

Overall I’m a story teller and so the titles aim to add to the overall narrative of the work.

CBP: The tone of your work feels melancholy, nostalgic and occasionally ominous – (the fireplace graphic as an example). Can you discuss if this is evoked intentionally, or a sensibility that comes out organically out of the painting process?

AH: Throughout my career from my earliest days at art school, to the present day, my work has persistently been described as feeling ‘unsettling’ ‘ominous’ or ‘nostalgic’. Out of the three descriptives I’d say I use a lot of memory work when making images so feelings of nostalgia naturally occur whether intentional or not. However unsettling and ominous are two readings that I never intentionally or purposefully depict. Although I agree to an extent that the work does conjure these sorts of feelings.

I to this day am not entirely sure where it comes from or why I do it. I suppose the work seems too often be set in a sort of fictional landscape, with a fictional time, a twilight perhaps and so the colour palette and saturated colours speak to that nature. But as for intentionality I’m not sure, it’s something I think about a lot.

CBP: ‘Allegory of Time’ is a distinctive collage-based painting which echoes compositional devices and divisions of space in your other paintings. Is this work unique to your practice and how did you approach and consolidate this work?

AH: I would say that this work is definitely unique in the way in which i have employed multiple materials, such as bronze, acrylic plastic and wood as well as paper, raw canvas, coloured pencil and paint. But not unique in the way in which I think about the division of space or the composition of work.

My work is made through the exploration of landscape via multiple avenues be that self referential, historical, local etc. and so in this work I tried to use different materials and their materialities to comment or mirror these references. The nature of a materials inherent meaning, its worthiness and what it depicts are all things I’m very interested in.

During my MA when I made this work I had all the workshops and materials as well as staff and technicians to help me realise a lot of these idea. Since I haven’t had quite so much opportunity to explore materials in this way. Having said that I have just began some new more accessible material explorations in stone carving and paper making which I am very excited about.

CBP: Describe a typical day in your studio and your approach to painting.

AH: Well of course it starts with a walk via the back lanes through the hedges and fields to the studio, followed by the ritual of making a pot of black coffee. While that’s brewing I’ll have a little tidy up and an assessment of what I’ve got on the go.

I’ll get sat on my chair that I salvaged from the side of the road in Battersea Park in London about three years ago and spend a good 10,15, 20 minutes just looking. Sometimes if I’m a bit further along with a painting I’ll just crack on with what I already know I’m going to do, but a lot of the time I need to have a look at some reference books or do some drawing, draw my own painting that is.

Although I work from my own drawings a lot I don’t often have a full resolved idea of what the work is going to turn out like, especially not the colours. And so the painting develops in quite a step by step reactionary way. One thing aids in the decision making of the next. Of course there’s lots of stopping and starting, sitting and thinking, I often think we as painters spend most of our time purely looking rather than painting. Except that is (for me anyway) at the very beginning of a painting or at the very end. The excitement of the fresh page and the excitement of the finishing touches, that’s where it’s at for me. When I can dissociate and hours can fly by in what feels like minutes.

I’ll often have little breaks where I’ll go for a wander make some more coffee, almost always accompanied by some kind of history podcast, or music, which varies depending on my mood.

Living in Lancaster and not having so many artists to talk to on a regular basis I have developed and have come to really appreciate the sort of cafe culture and the people I have met through this. My conversations with these people about what I’m doing and what they are up to also really help, they aren’t artists and so their insight or commentary is much more grounding. They make their way into my paintings this way too.

I’ve never been a late studio worker, I prefer the new air and quiet of the day. I’ll arrive around 7-8am and leave by 5-6pm at the latest.

CBP: What projects and body of work are you working on at the moment?

AH: Well as I mentioned above I’m really keen to start thinking a little more about expanding my use of materials. It’s taken me a while to lean back into living and working in the Northwest but slowly the natural and local materials are starting to enter my head space and its becoming a little clearer why and how I might use them.

Some are seasonal which I enjoy the idea of and so I’m waiting patiently for those materials to appear and harvest while I can, conkers or the right time of the year to cut branches for weaving, that kind of thing.

I have a show coming up in Preston that focuses on female painters living and working in the northwest which I’m really happy to be a part of. It’s seeming like there has been a bit of a push recently and some mobilisation by the way of representation and visibility of artists in the north especially within painting, a less London centric view is always refreshing.

I have some exiting news that I am yet to announce happening in the new year but you’ll have to wait to hear about that.

Abigail Hampsey is a British landscape painter, maker, storyteller and imaginer. Born in Lancashire (1996) She received her BA in Fine art from Newcastle university (2019) and her MA in Painting from the Royal college of Art (2022). Abigail’s work has been exhibited throughout the UK, including WORKPLACE Gallery, London, The Holden Gallery, Manchester and Gallagher and Turner, Newcastle, amongst others.

Abigail was the recipient of The Basil H.Alkazzi Scholarship Award in painting at the Royal College of Art (2020-22) and has been shortlisted for multiple awards such as the Beep Painting biennale and the Jacksons art prize (2023). As well as this Abigail is a painting tutor at Newcastle University, a baker, a farm hand, a barista and a member of the Contemporary British Painting collective (2023).