Amanda Ansell: Artist of the Month

Artist of the Month August 2021: Amanda Ansell, selected and interviewed by Paul Newman for CBP.

CBP: Looking at these small, square, and perfectly formed abstract paintings they give the impression of a painted equivalent to an aspect of a natural environment; a cropped close up of looking through or moving through wet reeds or grass, close to the ground. I think you can get a sense of this even without reading about the context of your work. Can you discuss something about the connection between sources of inspiration and the work’s autonomy as abstract painting?

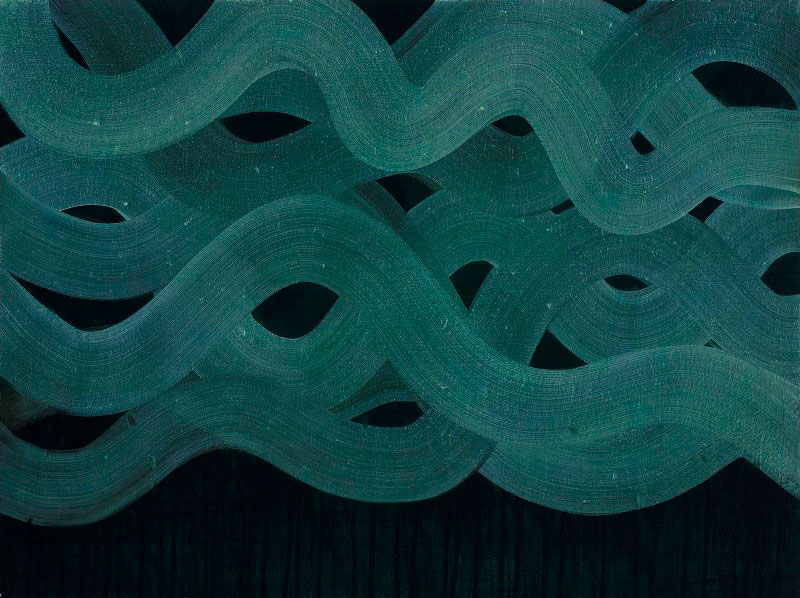

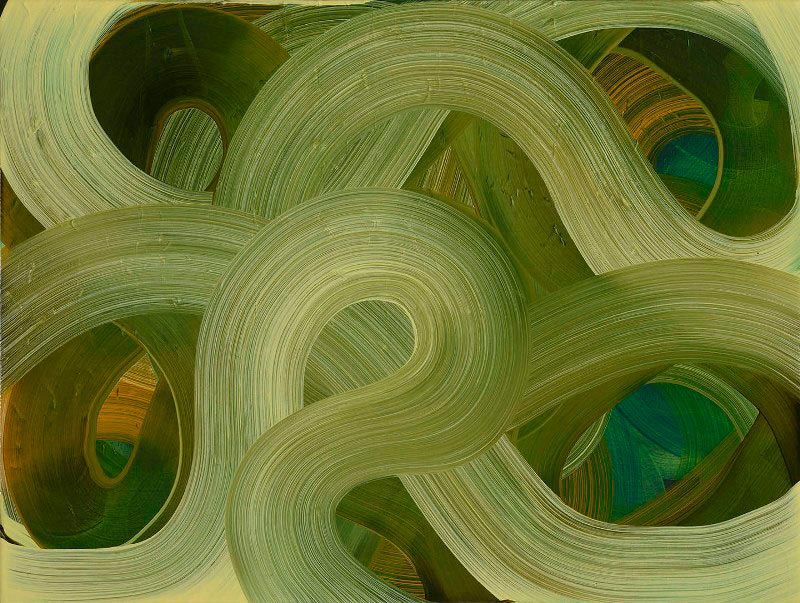

Amanda Ansell: For sure, there’s a correlation between the rural and the expansive. My studio is on the water’s edge between Suffolk and Essex, so I have a constantly changing watery environment all around me. There’s a stimulating connection between my immersion in the landscape and a desire to paint abstract works. This pairing is based on continually recurring themes such as nature’s seasons, circular forms, and swirling motion. The sensations of being in this landscape, combined with an eye for curved formations are translated into abstract notations that are multi-layered reworkings of paint and the painted surface. In fact, I first started making abstract works based on an immersive experience of being in the water and the interaction between two or three movements twenty years ago, so my practice has gone full circle.

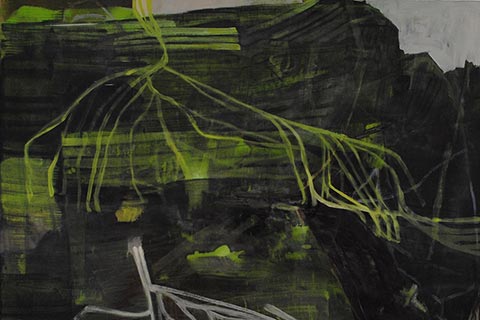

CBP: The notion of close to the ground is a feeling I have from your work. And this can be linked to painters like Michael Porter and Graham Sutherland’s landscape work. Is this a significant aspect to you, in terms of observing, experiencing, and re-imagining through your painting?

AA: Very true, I do a lot of walking and there can be a synesthetic encounter when wandering through the long grasses of nearby meadowland. I’ve been roaming the sides of the riverbank since I was small and recognize that I’ve developed an appetite to be enveloped by the watery landscape. It isn’t simply a case of travelling from point a to point b but having my feet on the ground, near to the water, and feeling held by this space. I love how British landscape painters like Michael Porter and Graham Sutherland drift between abstraction and landscape, generating paintings that have encountered the flow of nature. To me, they suggest we get a little closer, to allow the effects to permeate our sensibilities.

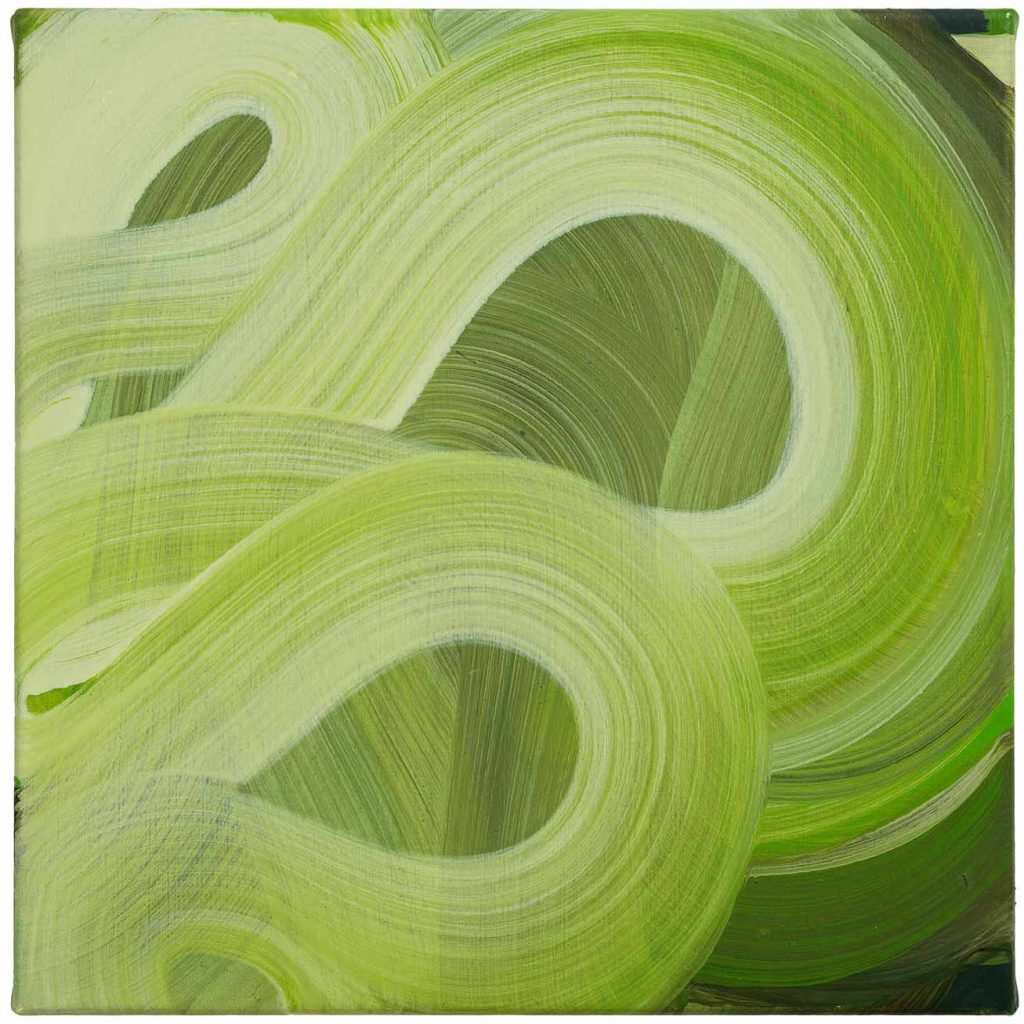

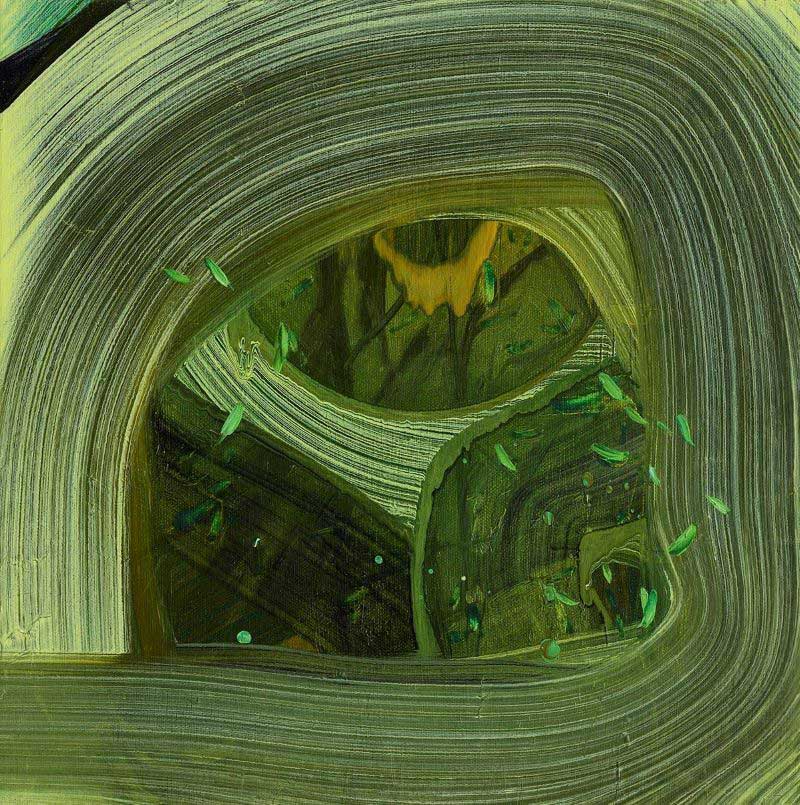

Winter Bloom in the studio, oil on canvas, 30cm x 28cm, 2021

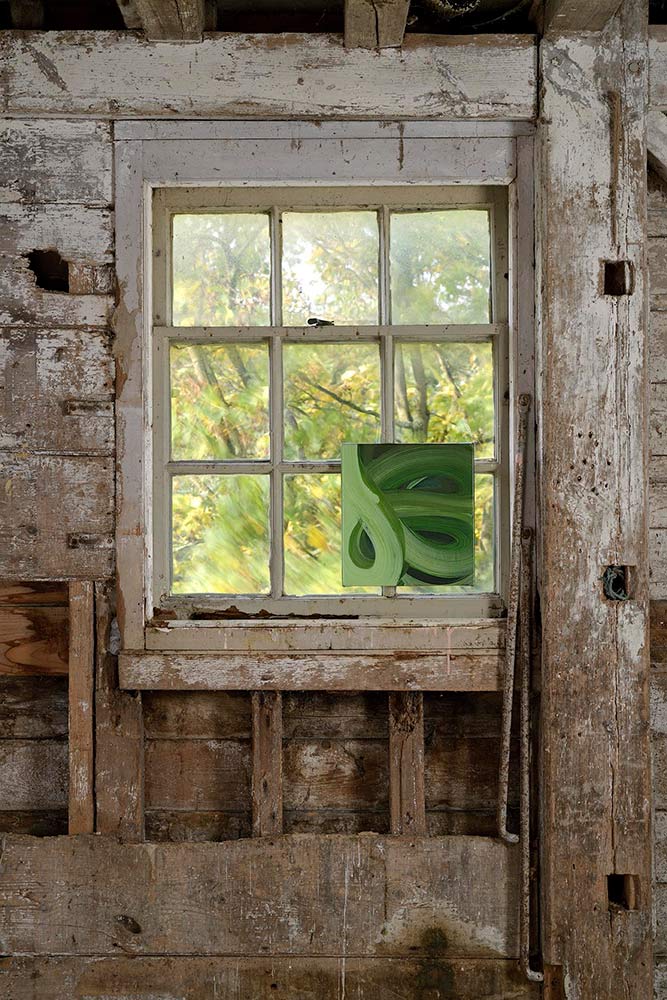

Studio view, 2021

CBP: Light feels like a key aspect to the work, reflected on the surface and coming through from the layers beneath. It connects to the notion of transparencies and building and revealing of layers in a painting. Could you discuss how you interpret and evoke light in your paintings?

AA: Yes, I am very conscious that I strive for that glowing energy; a radiance coming through from the underpainting, a delicate touch, and soft gesture, the effortless union of painted layers, where I achieve that brief sensation of all components merging without burden. It is sunlight, changing light, the quality of light, it’s certainly something precious. It’s also about the artist’s loss of self when engaged in the act of painting. I enjoy working with transparent colours and in particular the hues of yellow and brown. The quality of transparency and light is a natural progression of ideas in terms of addressing the landscape, starting with the earthy browns and moving through to the luminous greens and on to silvery whites.

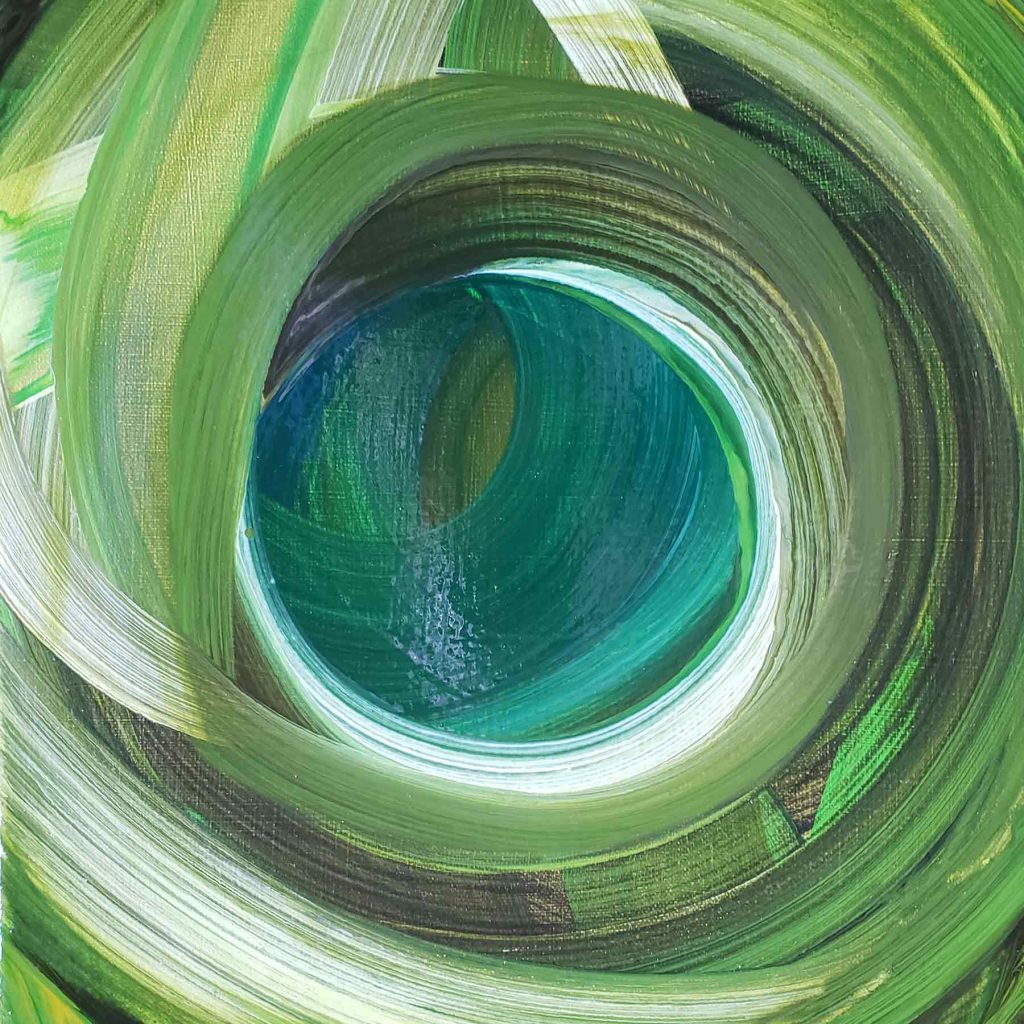

Work in progress, Circles, oil on canvas, 30cm x 30cm, 2021

Orbit, oil on canvas, 30cm x 30cm, 2013

CBP: The colour green feels like a very logical choice for these works, it’s incredibly rich and evocative. I remember visiting a Cy Twombly retrospective at Tate and though he wasn’t my favorite painter or exhibition at the time, I was unexpectedly enchanted by a later series of deep green paintings in the show that seemed clearly inspired by riverside landscapes and Monet. Could you discuss the use of colour in this body of work, perhaps in relation to how you used colour in previous series?

AA: Totally agree – Cy Twombly’s large, cascading green paintings are persuasive. I think it was Monet or Cezanne who commented “colour is an assistant” because when you are in nature you can simply reference the chromaticity around you. I moved to using analogous colours from purple-blue through to green and yellow when I started connecting to and referencing landscape in my work. Before this, I was making a series of foam bubble islands in abstracted seascapes and they employed a monochrome, greyscale. These paintings are rooted in notions of impermanence and coincided with a decision to move from London to Suffolk.

CBP: These small-scale works have complete self-contained compositions, yet are also like cropped fragments that also suggest the world beyond these picture frames. I’m not sure if it can be directly compared to photography, but could you discuss cropping and the sense of scale you explore in these works?

AA: Yes, the cropping of curved lines and gestural motifs is part of a repetitive routine that becomes a self-perpetuating method for making abstract paintings. I began producing line drawings that recorded the movement of water, and I wasn’t sure what would become of these doodles. I noticed how the lines fitted together and then thought about how I could use them in a process of layering liquid paint on the canvas. I repeated the technique, took note of the organic patterns and the empty spaces in between the curves. Sometimes I’d crop these formations and look for small, self-similar arrangements within. Scale is instinctive and balances with the size of the canvas.

CBP: You talk about the context of where you live and your studio in East Anglia in Constable country and heritage to Romantic-era British Landscape painting. Did you locate there with intention in response to the direction of your practice and or was it more an instinctive relationship that formed due to the circumstances of your surrounding environment?

AA: I think you could say it was instinctive. Whilst still living in London, I deliberately searched for artist opportunities in East Anglia. I was awarded an artist residency at firstsite in Colchester, Essex. This helped me to move out of London and start a life in Suffolk. It was timely and I was able to reconnect with the landscape that was a significant part of my upbringing.

CBP: What is the starting point for these paintings? What goes down underneath and gets covered by these curved, liquid brush strokes?

AA: I start with two coats of unbleached titanium dioxide. This provides a stable ground for all the layers that follow. I apply the oil colours one at a time, drawing curved lines on the canvas, and then reconfigure these painted lines according to my final form. There can be seven or eight layers of paint. When there are too many overlays, things can become quite subdued and heavy and the painting becomes move about the tiers and what lies beneath. I never scrape back the surface and prefer to let the layers dry and then use a transparent glaze to highlight something below.

CBP: Can you reveal any particular tools or techniques you use to construct these paintings?

AA: There’s nothing remarkable, I use standard flat brushes. Usually, the size of the brush fits into the width of the painting approximately five times. This feels like the correct fit in terms of scale and the size of the brushstrokes. When it comes to technique, I employ methods of traditional oil painting, layering up the surface using dark colours first, and working through the lights and the brights.

CBP: You’ve cultivated a gestural motif that seems to take care of itself with spontaneous precision. I remember reading an interview with a famous process painter, I can’t recall, maybe Ian Davenport, who talked about the hit rate in their work and the number of wasted paintings that get destroyed. What is your hit rate? Do you end up binning works? Or do you progress all your work to an endpoint where some might be more layered than others?

AA: No paintings are binned. I just keep on going and apply another layer of oil paint. If I do reach what I think is an endpoint, the canvas is put to one side, and I use this to experiment on or practice a gesture. Hopefully, a happy accident will occur and there’s an interesting outcome in relation to what was on the canvas before. My hit rate? I really try not to think about making a finished painting. I have lots of works on the go at the same time. An unresolved painting becomes the groundwork for something new.

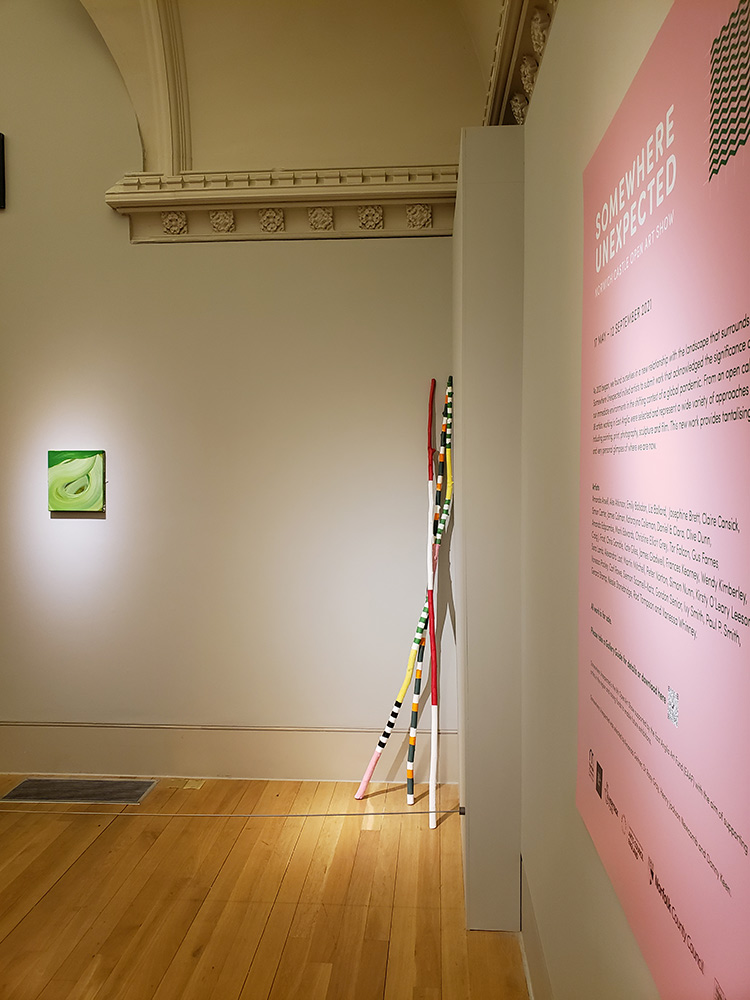

Included in this image, Dowsing by Carl Rowe.

CBP: You’re currently in Somewhere Unexpected at Norwich Castle, which explores artists’ relationships with their environments during the lockdown. Did this period affect the development of your work, or further intensify your scrutiny of the surrounding environment and source for your work?

AA: Yes, Somewhere Unexpected continues until Sunday 12th September 2021 and addresses the significance of our immediate environment in the shifting context of a global pandemic. I was fortunate to make it along to my studio space and continue my practice during the lockdown months. Instantly my observations of the landscape intensified, and there were moments when time seemed to slow down and this allowed for careful study of the transient effects of light. Annoyingly, I overpainted some works during this time, as the initial impact of the pandemic on my psyche was not conducive to making calm, gestural works. However, I did authentically connect with the landscape and experimented more.

Amanda Ansell was born in Sudbury, Suffolk in 1976 and studied at the Norwich School of Art and Design and The Slade School of Fine Art. After studying and painting in London for eight years Amanda returned to Suffolk in 2006 to begin an artist residency at Firstsite, Colchester. She exhibits widely and has work in both national and international public and private collections.

Amanda Ansell currently lives and works on the Suffolk / Essex border.

Recent exhibitions include:

2021: Somewhere Unexpected, Timothy Gurney Gallery, Norwich Castle, Norfolk, Nowhere, Cley 20/21, Norfolk.

2020: Vitalistic Fantasies, Cello Factory, London, The Royal Academy of Arts Summer Exhibition, London, Vitalistic Fantasies, Beep Painting Biennial, Swansea, Wales (online), Yes/No, Contemporary British Painting, Virtual Open Studio, #curatingforcorona, Kath&Company, Digital Showcase.

2019: Made in Britain, The National Museum of Gdansk, Poland, Mountain Size, Pineapple Black, Middlesbrough.