Daniel H Bell: Strange Nature

by Louisa Buck

This essay about the work of Daniel H Bell, winner of the CBP Prize 2024, was published in the CBP Prize 2024 exhibition catalogue. The essay forms part of the prize.

‘Every normal human being (and not merely the ‘artist’) has an inexhaustible store of buried images in his subconscious, it is merely a matter of courage or liberating procedures … of voyages into the unconscious, to bring pure and unadulterated found objects to light.’

Max Ernst

Daniel H Bell’s small, strange paintings snag the eye and embed themselves in the psyche. The more you gaze into the limpid translucent surfaces of these mysterious mini mises en scène, the odder they become. Things dematerialise and morph into something else altogether and it’s never clear what exactly is taking place. In ‘Dusk’ (2024) a bulbous brown shape with what looks like a single cataracted eye and ending in a trio of chunky white tentacles exhales a pair of delicate white bubbles which waft upwards against a crepuscular pink and blue backdrop too smooth to be sky. Are we looking at a sporing fungus, the death throes of a beached sea creature, a gruesomely severed udder, or all or none of the above?

Even when we know what we are seeing, we can’t quite believe our eyes. ‘Caterpillar’ (2024) fulfils its title by depicting the stripy yellow and black larvae of the cinnabar moth, but why are these critters pouring from the severed neck of a dead donkey? And what about the demonic blue eyes glaring out from the ectoplasmic cloud in the foreground? Just as the surrealists revelled in the spark to the subconscious fired by the unexpected combinations of unrelated objects, so Bell finds inspiration in the suggestiveness and subversive energy triggered by unplanned shapes, forms and encounters. As Max Ernst declared, “creativity is that marvellous capacity to grasp mutually distinct realities and draw a spark from their juxtaposition.”

In common with Ernst, Magritte et al, many of the images in Bell’s paintings are arrived at by chance, often snapped on his compact camera during walks in the countryside. These grabbed pictures are then worked over back in the studio and filtered through Bell’s vision. The prone donkey was originally spotted by Bell whilst it was sleeping in a field, and in a recent painting ‘Newt’ (2024) Bell brings about the unholy union of a scarily enlarged human-like hand of a dead newt discovered on his rural wanderings, combined with a picture he recently took of his mother, both of which are then fused in supernova-like clouds of paint. Often inspiration can arrive out of the most mundane moments. The ghostly faces emerging out of the painterly shadows of ‘Damp’ (2024), as its title suggests, have their starting point in the spots and splodges of a damp attic wall; and as well as appreciating their smooth surfaces and crisp edges, Bell’s decision to work on modestly sized found blocks of previously used wood, MDF or hardboard, is in great part so that their stains, marks and knotholes can offer a route into future imagery.

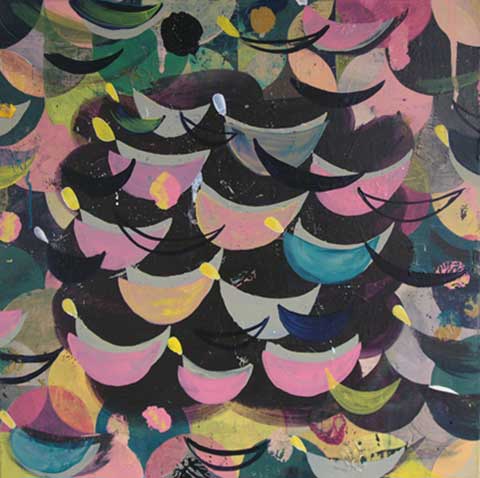

In the same spirit as the automatic methods used by the surrealists, Bell also uses the paint itself to throw up more suggestive shapes and dictate the course of a work. He makes a point of mixing a variety of substances: acrylic, oils, varnish, emulsion, filler and even fake blood can all co-exist in a single work. These are then built up in layers on the unyielding grounds of wood and MDF upon which they can bleed into each other and react in often unexpected ways. He always has several paintings on the go in the studio at the same time, which he leaves lying flat upwards like creative Petri dishes, so he can move between them, observing and reacting to what is happening on their surfaces. “I like the unpredictability of not knowing what things are going to do as I’m using them,” he says, and then only finding over time “how they mix together and change, and then how I can manipulate that.”

Bell did a degree in painting at Glasgow School of Art, but by the time he graduated in 2003 he wasn’t interested in making paintings any more. For a while he made kinetic sculpture and then went to Norwich School of Art and Design and took an MA in Digital Practices. However while the course gave him useful skills in animation and sound design, he still found himself drawn away from the digital and back to the tactile and the material. After a few subsequent years working in nature conservation and making a more in-depth study of biology and the natural world, Bell returned to making films that increasingly reflected his love of the stuff of things. Through making models for these early films and animations he rekindled an interest in creating textured surfaces, and, as he puts it, “painting crept back in.” But while these more recent and ongoing paintings still pay tribute to the artists Bell admires – from the morally ambivalent, tragi-comic figures of Philip Guston to the dark fantasies of Goya and the sumptuous symbolism of Odilon Redon – unlike his earlier works they are no longer predicated on specific content. Now the paint itself takes centre stage as the active protagonist.

For the past few years painting has co-existed with the moving image as two complementary and equally important strands in his work. Their relationship is symbiotic. The films provide a rich source of imagery for his paintings and his paintings can often be glimpsed in the background of the films. At times the paint is unleashed as an animated glopping, plopping liquid filmed presence in its own right. Like his paintings, Bell’s films are modest in scale but pack a hefty psychological punch. Brief hallucinatory fragments, they flare up to capture visceral, magical moments of natural entropy and oddity, often accompanied by peculiar guttural, scratching abstract sounds that are the fruits of Bell’s field recordings. Both film and paintings take their starting point in often random encounters with the natural world that can be scary, funny, beautiful and repellent, sometimes all at once.

In one film – they are all untitled – the hugely magnified single eye of a slug swivels at the end of its stalk to scrutinise its surroundings; in another we get uncomfortably up close and personal with a snail as it noisily consumes a blade of grass. A stoat runs past a camera left out in the wild. Wonkily taxidermied birds or parts of birds are reanimated, with the webbed clawed foot of a dead coot memorably made to flex in a deeply disquieting way. For just a few seconds a dead cinnabar moth comes back to exaggerated life to buzz and quiver convulsively, attached to the dual leads of a tiny motor. Chilli peppers dangle damply and lumpily off their plant to an ominous electronic sound track, and a fully formed blackberry miraculously pops up out of a purple stain. Even Bell’s dog is given the uncanny treatment as she careers through sea and snow to a soundtrack by experimental German rock band Faust while due to some nifty reverse filming, the steam of her frosty barking breath is dramatically sucked back into her mouth.

Bell is particularly fond of fungi, their forms and colours and the way they can mutate, explode, seep and shapeshift. They infiltrate his paintings and often run amok in his films where various fungal species occasionally acquire eyes and skedaddle around; or are time-lapse filmed as they bloom, sprout, collapse or simply exist in all their weirdness. The wonderfully named King Alfred’s Cakes, a fungus species that cross-dresses as a potato and produces copious piles of sooty black spores, makes a number of appearances and there’s also a memorable sequence of pulsating oyster mushrooms. Puffballs are another favourite in their many modes, as is the Blusher Mushroom, a type of fungus that resembles a crusty loaf of bread.

But while Bell’s work is testament to his close and often tender engagement with nature there is nothing cute or romantic about his relationship with the natural world. Death, entropy and decay are treated with a dark, unsentimental humour and a refusal to idealise. There’s a bodily sense of flux and a whiff of the repellent in the shifting turbulence of his smoky paint surfaces and the unsettling hybrid beings they coalesce to form; while in his films the animal, the avian, the amphibian and the fungal all assume distinctly human qualities. In Bell’s peculiar free-association scenarios nothing is fixed or finite and it is impossible to settle on any single meaning or interpretation. In his work as in the world at large, everything is interconnected and in a perpetual state of motion and metamorphosis. This is what makes these paintings and films so compelling. We gaze into their unfolding realities in much the same way as Bell himself peered as a child into the enticing depths of the wild pond near his family home in Shropshire. We cannot resist looking, and there is both trepidation and also excitement in not knowing quite what we might find.