Dr Judith Tucker: Artist of the Month

Dr Judith Tucker, 1960 – 2023

This month to celebrate the life and work of the late Judith Tucker we are featuring this Artist of the Month interview from May 2022.

Judy was a passionate advocate for painting in all its forms, a caring and compassionate educator, a formidable academic, and a loyal friend. She recently took on the role of Chair of Contemporary British Painting, alongside her very active painting practice, and position as Director of Research: Culture and Impact at The University of Leeds.

As an artist and academic, her work dealing with landscape, place, and memory, transcended a single aesthetic or scale. She painted the edges, the things that might reward a more focused reading. Recent series of work included the ‘Night Fitties’, showing ‘the play of light and dark and the uncanny transformations of the chalets on the Humberston Fitties that take place after hours as well as notions of vulnerability, precarity, occupation and emptiness’.

Judy was a catalysing presence; funny, warm and generous to a fault. Her enthusiasm for painting’s powerful influence to bring people together, was infectious and it was rare to leave a private view with Judy in attendance, without having made a new friend or connection.

In memory of Judith Tucker, her partner the poet Harriet Tarlo is setting up The Judith Tucker Art Prize. We can think of no better tribute to someone who supported other artists so selflessly. If you would like to donate you can do so here: Just Giving

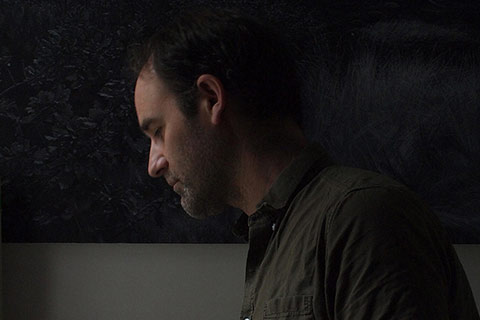

Judith Tucker, selected and interviewed by Paul Newman for CBP

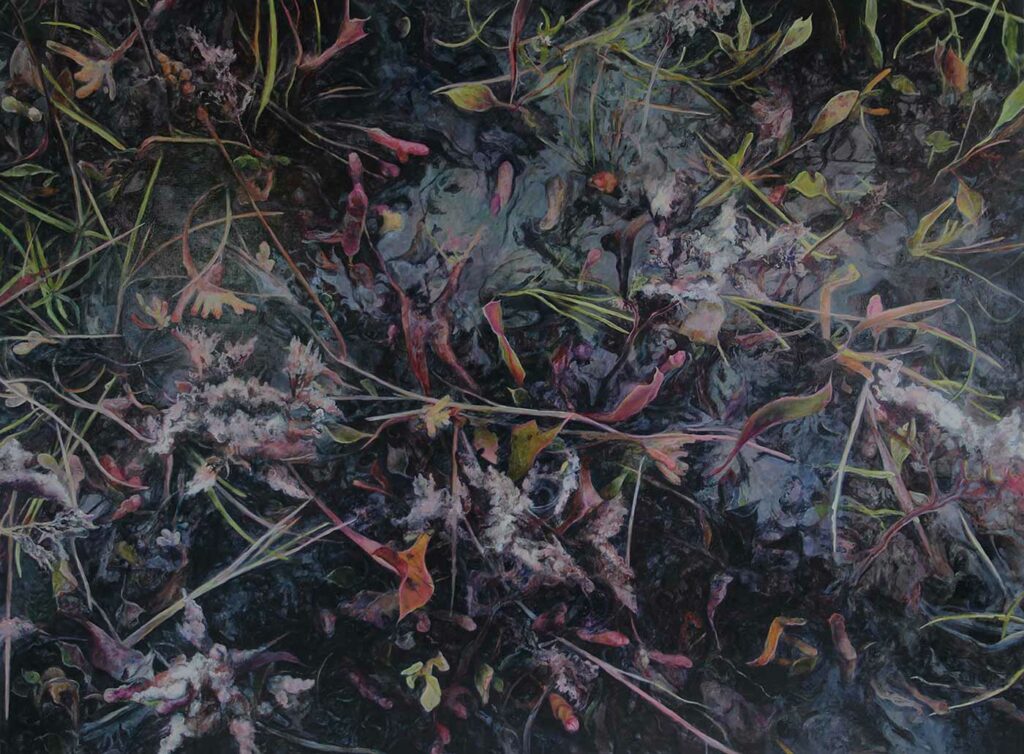

Judith Tucker’s work explores the meeting of social history, personal memory and geography; Night Fitties explore the play of light and dark and the uncanny transformations of the chalets on the Humberston Fitties that take place after hours as well as notions of vulnerability, precarity, occupation and emptiness. The work considers, in the shadow of recent dramatic political changes, how notions of place and identity are constructed on domestic and larger scales, as reflected by the play on flags and other indications of Englishness. They investigate the relation of social, environmental and energy politics on micro and macro scales, looking out to land and sea and back to the community.

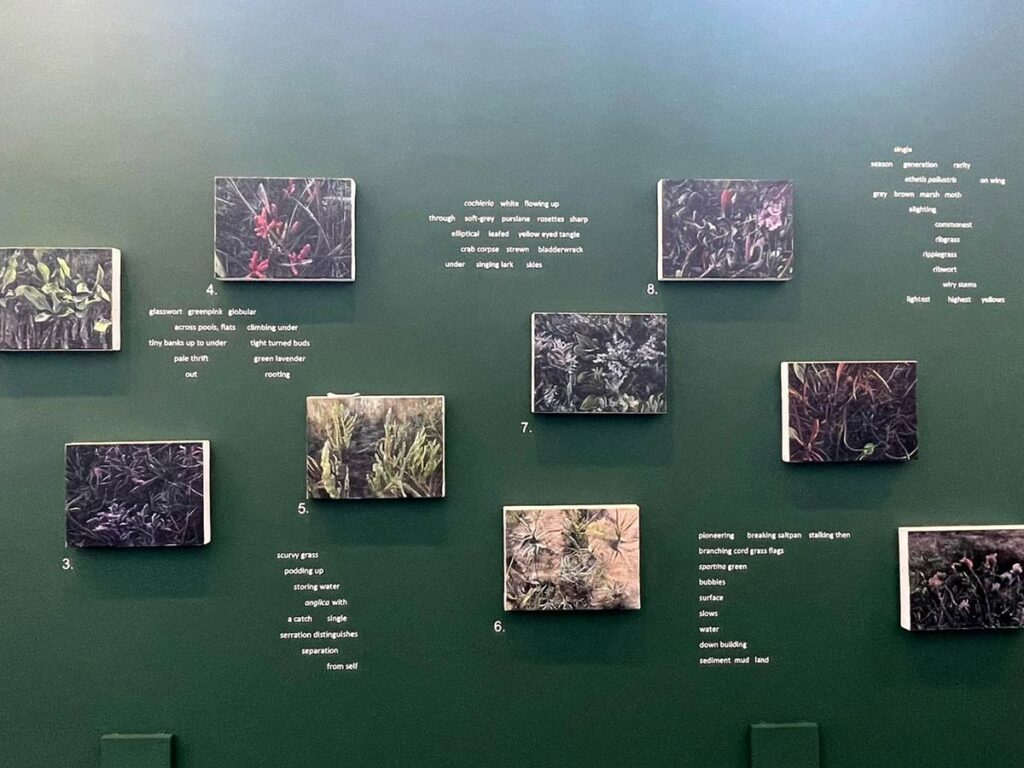

The Dark Marsh series considers the pioneering salt marsh plants of the Humberston Fitties, Tetney Marsh area, consider plants that are both vulnerable to sea level rise, but that also help to protect the land from flooding. The work is intended to be seen in relation to the Night Fitties work and together it explores human and more-than-human worlds in microcosm and juxtaposition, touching on the play of light, tide and colour, uncanny transformations after dark, and notions of vulnerability, occupation, resilience and reclamation.

CBP: For a number of years, you’ve been painting the Humberston Fitties; a sprawling community of independently built holiday chalets on the Humber Estuary, that first emerged in the 20th C interwar years. What drew you to this as a research project? Was there an affinity sparked by your own experience of a place or memory?

JT: The Humberston Fitties is in Northeast Lincolnshire and is one of the last remaining functional plotlands in the UK representing the threatened phenomenon of urban working-class owned rural space. The self-built chalets, shacks, and sheds of the Fitties lie low behind marshy beach and dunes, always liable to flood, to return to their former state. I first came across it in 2013 when doing some work on the NE Lincs coast between Cleethorpes and Tetney, thanks to an Arts Council England (ACE) commission with the poet Harriet Tarlo via the curator and CBP artist Linda Ingham. At first, the Fitties was a small part of a larger project and the chalets somewhere fun and unusual to stay when doing fieldwork, but gradually we became drawn to the individualistic properties and people, the stories, and histories behind the chalets and the whole plotland movement. Travelling to a particular place, making work on location, and then developing this material back in my studio, has always been a fundamental feature of my painting practice, however, while the selected locations have changed over the years, coasts and holiday resorts have been an ongoing obsession. I think that’s partly because when I was a very small child I lived on Anglesey with views of the sea. We moved to London, I remember thinking that it was a very dark and crowded place and I felt hemmed in and trapped, I really missed running on the beach and the atmosphere of a small seaside town both in and out of season and in a funny way I’ve been trying to paint myself back there ever since. I do think that this experience must have been influential in my later, deep interest in holiday resorts. Coasts are places which are a mixture of tourist idyll and of have a history of military importance too. They are places in which pleasure and violence, potential or actual, seem to be inextricably intertwined. For example, there are two World War 1 forts in the Humber and concrete embrasures overlooking the saltmarshes and the chalets themselves were requisitioned, and some of them are prefabs from army bases.

CBP: You also paint a complementary series of close to the ground flora of the Humber Estuary, the Dark Marsh paintings. The two series complement each other and there’s a strong narrative of where wilderness meets human made infrastructure, overgrown nature intertwines with the slightly dilapidated and run-down architecture. It feels like a continuing theme throughout your practice; on the periphery where nature and concrete meet. Can you talk about this meeting point?

JT: Perhaps the works might remind us of our interdependence and the importance of slow looking and the importance of paying attention to marginalized plants and communities alike. Like all localities this is a changing place where human interventions and priorities intersect with the short- and long-term, large- and small-scale nonhuman changes such as the reshaping of land by water in tidal surges. The word fitties itself is an old word for saltmarsh and the work I make there is always in conversation with the landscape, the surrounding marshland from which the Fitties was sculpted. The marsh, beach and natural environment are intrinsic to what has drawn people to the area. Cleethorpes’s history is closely linked to industrialisation and the rise of the railways. In its heyday it was the destination of miners, steel workers and mill workers. For these people, seaside resorts were places to encounter the ‘natural’ for therapeutic mental or physical replenishment; they are all about interaction between humans and environment. The Dark Marsh paintings of the pioneering salt marsh plants from the adjoining Tetney Marsh area, considers plants that are both vulnerable to sea level rise, but that also help to protect the land from flooding. There is a tension between the marsh and the sandy beaches, there are lively debates on social media about the marsh encroaching on the tourist attraction of the sands, but the marsh itself is so valuable ecologically. This work is intended to be seen in relation to the Night Fitties work and together it explores human and more-than-human worlds in microcosm and juxtaposition, touching on the play of light, tide and colour, uncanny transformations after dark, and notions of vulnerability, occupation, resilience and reclamation. It is precisely the relation of environmental change and the climate emergency to class and privilege that emerges when the two series are viewed together. I should mention that not all the chalets are run down, many are now being renovated, with the rising popularity of staycations the area is being rediscovered.

CBP: You’ve been collaborating with poet Harriet Tarlo on the project Hideaway; Poetry & Painting from the Saltmarsh. There is a compelling relationship between some of the twisting sinewy rhythm of the poetry, listening to an audio version and the tangled and unruly subject of your paintings. Can you talk about how the collaboration came about and your working relationship, how you responded to the site and each other’s interpretations?

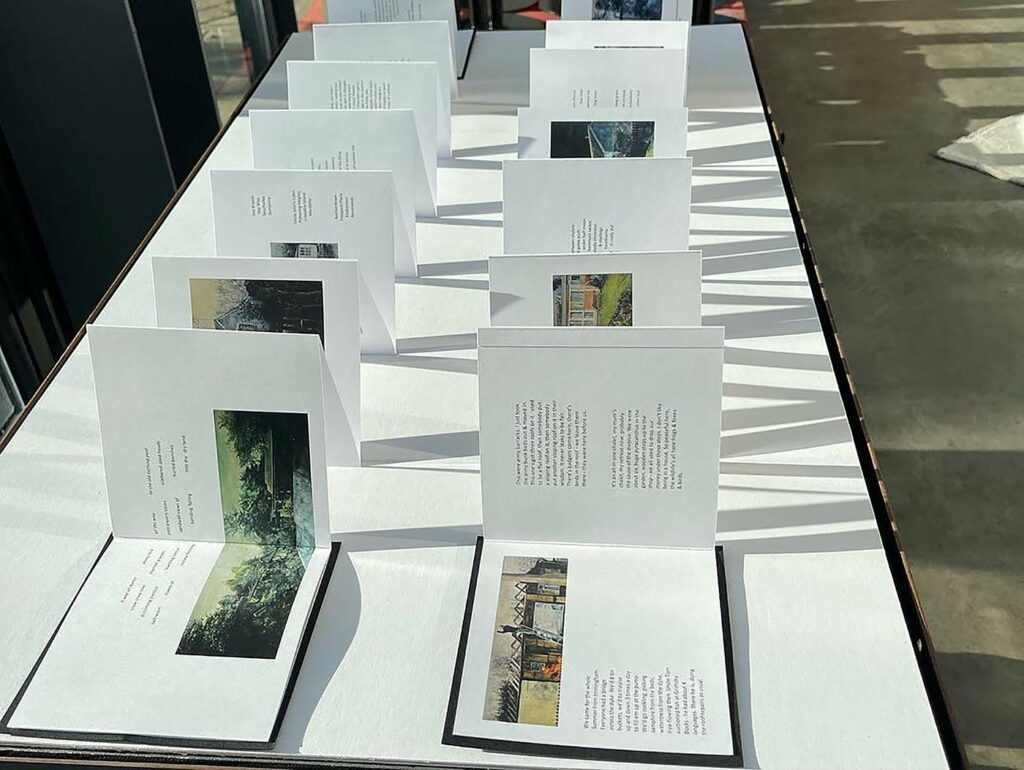

JT: I’ve been collaborating with Harriet Tarlo since 2011, while we have our individual practices, we also have an ongoing collaborative one. We start our collaboration with slow walking and slow looking, we both take zigzag notebooks into the field and stop intermittently in order to fill one small surface each with drawing and writing from the same location. Then we develop drawings, paintings, and poetry in an ongoing conversation, this doesn’t mean that the work always has to be seen together, but the titles are an acknowledgement of that collaboration. When we present the work together in exhibitions and artists’ books, we do not merge text and image but allow for space and separation between word and image, inviting the viewer in to make connections and join the conversation. Recently, we’ve also added QR codes to exhibition labels to allow a viewer to listen whilst viewing. This allows for unexpected aspects of our collaboration to emerge so for example silent, static paintings and drawings might become filled with the sound and movement of voices and language. Hideaway is a development of this work with an even stronger emphasis on ecology and conservation and we are thrilled that we have ACE funding for this. The exhibition currently on at 20-21 Visual Arts Centre, Scunthorpe has paintings and poems relating to the chalets, both past and present, in conjunction with poems and paintings of the salt marsh plants. Local historian, Alan Dowling, who we met shortly before he died, left a rich archive of historic materials relating to the Fitties which they would study in relation to what is there today. The archive includes both images and texts from and by local people going back several decades. Hideaway combines contemporary place-based approach with materials from over a fifty-year period through which we hope viewers may perceive the impact of environmental and societal change to both buildings and plant life

CBP: The Night Fitties series often feature sometimes dilapidated English flags and pirate flags. They are part of these chalets and their owners’ identities. Combined with a pensive twilight setting there are layered connotations to these works. Your statement refers to ‘in the shadow of recent dramatic political changes’ Could you talk more about these layered narratives in the works? Have they have taken on additional meaning in the years you’ve been painting this series.

JT: You are right about the many stories one can read into the paintings, for example in Why Destroy a Thing of Beauty? Is the flag being lowered in twilight in a melancholic timbre? Might the lights on the house stand in for. a displaced sunset? Conversely the painted sky is menacing and heavy, no sun breaks through the cloud, does this transform the chalet lights into sinister charlatans at the same time as being wistful hopes of comfort? When you visit the Fitties the flags fluttering are a really noticeable feature, some are simply playful and draw on seaside themes, and obviously there are times when the Union Jacks are more on display, for example, when there’s an important football match. Nonetheless the flags took on a different connotation in recent years. Lincolnshire was one of the highest pro-leave areas. The views of the Fitties inhabitants who largely supported the ‘Leave’ campaign, seem far from anachronistic now, but rather seem to represent a large percentage of the population who felt disillusioned with bureaucracy, unheard and disenfranchised by both Westminster and Brussels. The inherent mistrust of the establishment, the legacy of battles with the council, the tendency toward anarchic, defiant individualism, the long reverberations of the miners’ strike, all demonstrate that class divisions and strain in Britain are alive and well. In a small way, these paintings, and accompanying poems seek to explore those fears and couple them with the uncertainties of climate change.

CBP: Can you discuss the setting of these paintings in the twilight, in terms of creating atmosphere, uncertainty and tension and Romantism. And in terms of painting techniques, painting light?

JT: I think I began to answer some of this in the last paragraph, so I’ll riff a bit more here. I am really interested in having conversations with the long history of landscape painting as well as being in dialogue with contemporary places. I challenge myself to work both with and against notions and conventions of the romantic, of the picturesque and counteract ideas of the view. In looking as attentively at the marsh as at the chalets and placing the two adjacent to each other and to accompanying texts, we have a greater chance of avoiding the landscape clichés of bleak sublime invited by marsh and picturesque. I am also interested in rethinking the mid-century neoromantic painters in a radical contemporary way. Using painting to critique simplistic pastoral or bucolic views of British landscape is of course, nothing new. A key, mid-century example is Eric Ravilious, an artist whose landscape work also rarely included people, yet was far from nostalgic. He dealt with a pragmatic version of the rural imbued with the evidence of modern agriculture and the energy networks. Far from presenting a preservationist or melancholic view Ravilious’ work engaged whole-heartedly with modernity. In additions I am especially interested in what cultural geographer, David Matless, who has considered the Anthropocene in an aesthetic context, terms as the Anthroposcene. In a recent article on the subject, he uses the term “Anthroposcenic” to explore how landscape art might depict our new epoch. Matless reads the English coast, especially the East Anglian coast with its rising sea level, as an emblem of the anthroproscenic and the painter Julián Perry’s portrayal of this through chalets and static caravans as exemplary. Another artist whose work chimes with this notion is the filmmaker Esther Johnson: her two films ‘Hinterland’ (2002) and ‘Retreating the Line’ (2017) – concern the loss of land and destruction of homes through erosion around Skipsea, Holderness in East Yorkshire. The two films employ many of the same motifs: the teetering chalets and caravans perched on the edges of cliffs, images of cut off roads, abandoned holiday homes, collapsed pill boxes at the base of cliffs and the trope of the weathered fragments, road signs. For artists and writers including myself chalets, caravans and perilous residences on the edges have become places of anthroposcenic contemplation, perhaps a leit motif of the anthroposcene. In terms of painterly technique, it is through paint that I turn what might be a comfortable image of a holiday home or humble saltmarsh plant into an unfamiliar and uncertain place. These paintings developed out of processes of layering and meshing; they focus on surface, yet they also evolve out of the viscosity and liquidity of the paint. These processes sound like a description of the saltmarsh itself: what is always at stake in representational painting is the tension between the materiality of substance and its metaphor. In shifting light, the image emerges and is then obscured, refusing to be precisely pinned down. The smoothed, dragged, and modulated surfaces draw the viewer close in, glazes and compositions both offer an invitation to explore but ultimately deny entry to the viewer’s eye.

CBP There is a notion of a discrete reconnaissance in recording these chalets. It is implied the owners might be inside as night falls. How do you go about collecting your imagery and source material? And what connection or relationship do you have with their owners?

JT: As light falls, we go for walks, looking and photographing and making notes, we are just on the public roads and paths through the chalets to the beach and marsh. It’s peaceful and tranquil after the day trippers and dog walkers have gone home, the wildlife comes out, beautiful foxes and bats. The owners or holiday makers are certainly often there, and we do know many of them, as working with the chalet owners and holiday makers has become a really important aspect of our practice. We have interacted with the community through interviews and memory and creative workshops and our Facebook page Projectfitties. The Fitties folk are my first audience and I post my work there first and wait with bated breath for the reaction. Some of our exhibitions and publications include material drawn from community-written memory cards and interviews. We’ve been given old family holiday photographs of the site through the ages which are a wonderful record. For Hideaway we have also been working from materials in the Grimsby Archive. While my paintings of the holiday chalets rarely have images of people depicted within them, we know that these are places that are far from abandoned and are buzzing with human activities. Lights are on, the paraphernalia of picnics and DIY is in evidence everywhere. Actually, we have recently become owners of a chalet ourselves, so I think there will a lot more work coming from the area in the future.

CBP: Your painting style holds a balance between fact and atmosphere with great draughtsmanship and expressive painterly gesture. There’s a sense of drama and tension and a charm, they would also make great book cover illustrations. Could you talk about your stylistic approaches to painting?

JT: I think I’m trying to explore, to find out, to investigate and also to respond to what is there, but also to interpret and image and I really do think through making. So, I haven’t really thought of my work in terms of illustration nor really in terms of style, actually, but I do try to hold the balance between documenting the place and what the affective power of painting is and that’s a paradox that will never be resolved and it’s the driver that keeps me motivated.

CBP: Where We Live at the Millennium Gallery Sheffield features yourself, fellow CBP members Mandy Payne and Narbi Price along with artist curator Trevor Burgess, and Jonathan Hooper. You all paint specific locations of the ordinary and overlooked. Each of you have your own particular style and painterly interpretation of your subject. Can you talk about this exhibition and whether you feel you are part of a particular genre of contemporary urban, suburban and rural landscape painting?

JT: I am really delighted to have a group of my Night Fitties paintings shown in this show. The exhibition was Trevor’s idea, and he selected the five artists; but subsequently we have worked together and through discussion further links emerged, and what is interesting is what those painted locations reveal both about Britain and what painting can offer now. The resulting constellations of paintings reflect repeated considerations and permutations of a particular place, and the notion of series is key for all five painters. All five of us have spent years working from one particular location or architectural thematic, and when brought together the works do give an interesting and illuminating snapshot of the UK. Trevor’s extensive series developed from estate agent’s photos from London invite us to consider that where we live can so easily become not so much a home but a commodity. Jonathan’s subject is an extraordinary colorist interpretation of the legacy of nineteenth century housing in Leeds, the back to backs and suburbia are transformed into glowing images. Mandy’s ongoing exploration of Parkhill’s Brutalist and utopian architecture brings a subverted modernist painterly idiom into the twenty-first century, and the very weight of her small and exquisitely crafted concrete paintings seems emblematic of the tussle of how to live up to the hopes for living encapsulated in those estates. Finally, Narbi’s elegiac paintings of the former pit village Ashington now, are the at the same time most painterly with playful and experimental brushwork yet are the closest to documentary. I think that contemporary British landscape painting is at av ery lively point, at its crux is a consideration of the complexities inherent in the concept of ‘landscape ‘in its broadest reading in relation to painting. We all ask the deceptively simple question: what might it mean to paint ‘landscape’ here and now, in Britain in the twenty-first century? While, of course, paintings offer up as many questions as they answer, the vitality of landscape painting now is palpable: the works included deal with urgent issues of our time: political, aesthetic, and ecological. This exhibition and others demonstrates that landscape painting is radical and what might once have been considered an atavistic activity is burgeoning. The artists use paint in all its messy materiality and with all its metaphorical fullness, they do this in relation to both ‘real’ landscapes and representations of landscape and through this address key issues of our time.

Judith Tucker completed a B.A. Fine Art at the Ruskin School of Art, University of Oxford (1978 – 81) and an M.A. Fine Art followed by a PhD in Fine Art at the University of Leeds (1999 – 2002). Between 2003 and 2006 she held an AHRC fellowship in the Creative and Performing Arts at the University of Leeds. In 2018 and 2019 she was a finalist in the Jackson’s Open Painting Prize and in 2019 shortlisted for the Westmorland Landscape Prize. Other exhibition venues include Arthouse1 and Collyer Bristow, London and regional galleries throughout the UK, and further afield in Iasi, Romania, Gdansk, Poland, Brno, Czech Republic, Vienna, Austria, Minneapolis and Virginia USA and Yantai, Nanjing and Tianjin in China. When she is not in her studio, she is Senior Lecturer in the School of Design at the University of Leeds. She has a long-term collaboration with the poet Harriet Tarlo.