Gavin Maughfling: Artist of the Month

Artist of the Month January 2024:

Gavin Maughfling, selected and interviewed by Paul Newman for CBP.

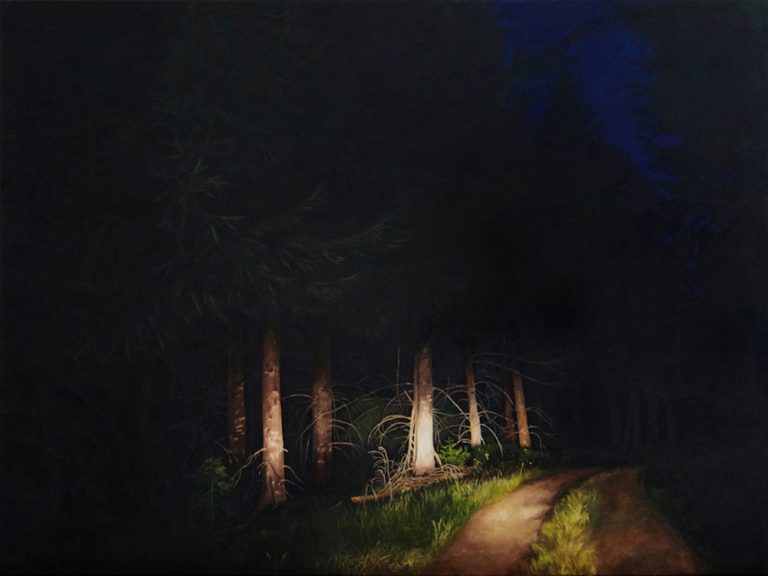

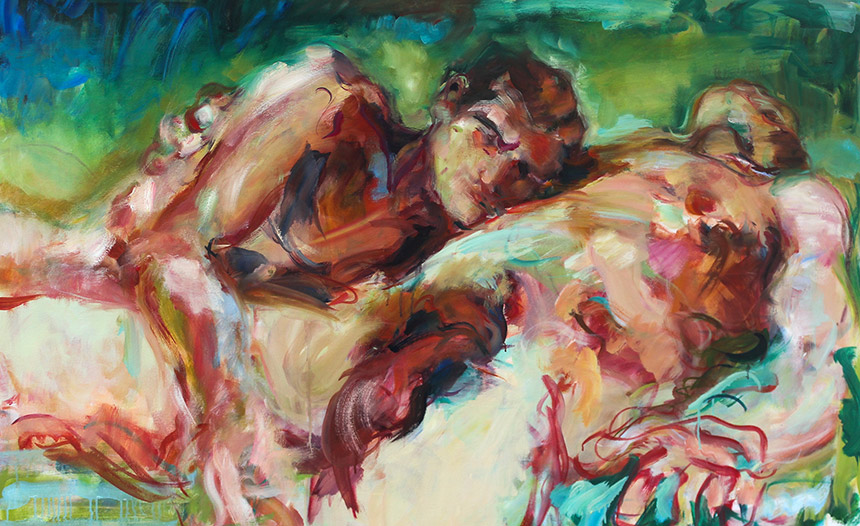

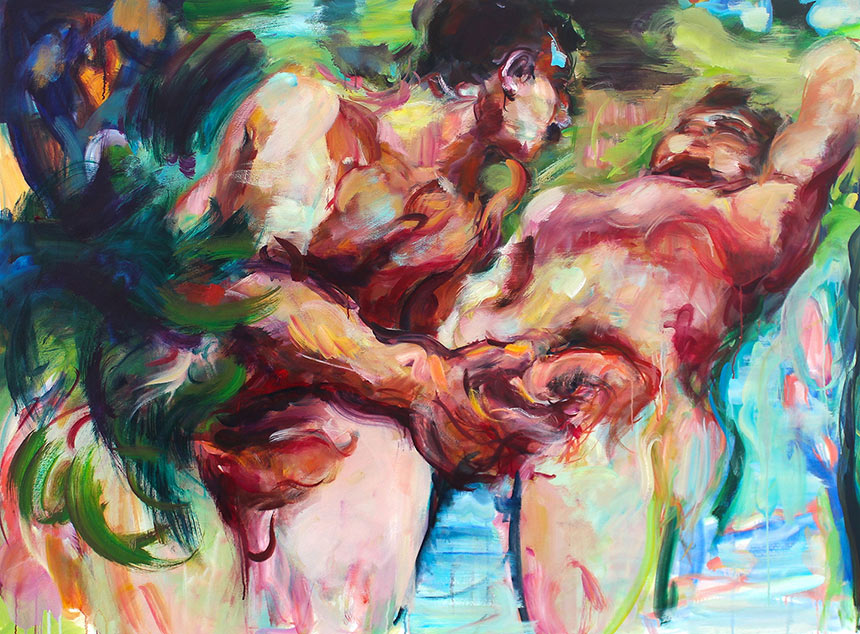

In his current work Gavin Maughfling examines vulnerability and power within queer relationships. The paintings take a range of sources as their starting point, including film stills, personal archives, and memory. Their locations include outdoor spaces in which nature serves as witness to human interaction, referencing in part the narratives of canonical painters such as Titian, in his Diana and Actaeon series, as well as the tradition of the bacchanal. More recently, the settings have widened to encompass depictions of interior domestic spaces. The works refer to the emotional spaces that are created both between strangers and within intimate relationships, and to the physical and verbal communication that takes place during and after sex.

The protagonists in these paintings are navigating a route that is sometimes perilous, through shifting frontiers of lust and affection, trust and fear, honesty and dissembling. Through their formal and physical language of gesture, space and colour, the works mirror the ways in which in real life we probe, using words, our bodies and our eyes, reaching for some kind of fusion between ourselves and the impenetrable other.

CBP: These are very passionate paintings with visceral, flourishing gesture, depicting male bodies and intimate physical and emotional connections. There appears to be a formal investigation into the push pull of figure / ground relationships in painting; from the Baroque to the paintings of De-Kooning and Cecily Brown. Can you introduce the broad themes of your work that you translate through your painting?

GM: Broadly, my work attempts to represent queer relationships in ways that are as true as I can get to all the complex social and interpersonal complexities that we negotiate. I wasn’t seeing this wider representation in visual art, especially in my field of painting. This is changing rapidly now, and in such exciting ways, in the works of painters like Salman Toor and Doron Langberg and Christina Quarles, and I am positioning myself somewhere within this context. More specifically I have been interested recently in how to show sex, not how it appears to an observer but how it feels from within, and the connections (and disconnects) that run between body and mind, act and feeling, and how it fits within wider relationship dynamics.

The formal investigations you refer to come out of this desire to find a way to show feeling from the inside, rather than describe or illustrate an external reality. The dissolving of figure and ground through gesture and colour, the struggle with paint – these are all a kind of dodge, a way for me of trying to avoid the illustrative mark, or the mark that suggests too definitively a fixed feeling or state, when what I am trying to capture is something much more fluid, and fleeing, and often contradictory.

You ask about ways in which I might be referencing the Baroque, or other schools and individual artist like say Cecily Brown or de Kooning. I think that these connections do help me find my way into opening up and responding to a subject. They can also add extra layers of allusion or meaning – some of my recent paintings for example have drawn on specific compositions by Caravaggio, without acting as direct transcriptions. And I think perhaps that these echoes can help a viewer in navigating their way through otherwise unfamiliar territory.

CBP: A physical and emotional struggle is depicted in the work, though it’s not explicitly violence, the lyrical, flourishing brushwork evokes something of Romantic era painting and earlier like Rubens. You also mention the notion of Arcadian space which is something of an ideal. Can you discuss the range of emotional tones that come out of your painting?

GM: I think that the struggle and physicality come from the desire I talked about previously, to show feeling from the inside – and especially perhaps to convey the push of conflicting emotions that can take place during sex, desire and unease running side by side both between two people and internally. Thinking about the lyrical or Romantic gesture, I do want to convey a sense of splendour. I’d like my paintings to have an effect almost like huge, richly woven tapestries hung together in a great hall. This engagement in thinking about large-scale and public works connects to your earlier question about the Baroque. A part of my aim is an almost political desire is to create public images of queerness that are magnificent and full of awe. And so, I strain every painting muscle of colour, mark-making, texture I have towards that end. I am engaging in these works with a range of emotions, from desire to passion, rejection to alienation, unkindness to compassion, loneliness to companionship. And there are others I haven’t reached or explored fully. I want to find ways down the line to represent gentle or conjugal love that are not too readily sentimental.

The question of violence is one I’ve not fully worked out. I’m very squeamish. However, there is something in certain painterly depictions of violence – say in late Titian works like The Flaying of Marsyas, or the Death of Acteon, that is compelling. They are incredibly cruel paintings, or rather, they are incredible paintings of cruelty, and they have a kind of melancholy grandeur. And yet I think that cruelty and violence are not at all beautiful in reality; rather, they are mean and low and ugly. So, I haven’t yet fully unraveled in my thinking the transformative function from violence to beauty that takes places in these works. The divine perpetrators (Diana, Apollo) are magnificent but detached and without compassion, while their victims appear full of pathos and physical disintegration. Perhaps the paintings’ splendour in paint and colour and composition are designed to lure us into the true meanings of the myth, or perhaps they are a sublimation (for us, for the painter) of violent desires.

The Arcadian space you ask about is such a rich container for thinking about narrative painting. It’s an existing motif that runs through art, and not only Western painting. It offers a boundaried world; an arena that can be almost theatrical into which protagonists enter and from which they depart, and where their dramas are played out. And it raises the question of our own relationship as viewers to the pictorial space we behold, whether as spectators on the other side of a proscenium arch, or as voyeurs, like Actaeon pulling back the curtain to spy on the scene, or even as latently active participants ourselves. This is of course like how painting often works, I believe; it is a framed boundary inside which elements interact, extending a dialogue across and outside the frame. In terms of queer experience, the Arcadian space can refer to the idea of crossing a boundary from the external, heteronormative world into an exclusively queer space; one which has different rules and, although frequently contested, one in which there exists a sense of shared understanding and history.

CBP: This article presents a separate series of works. One is based on movie stills from the film ‘Stranger by the Lake’. Can you talk about this series, how the paintings translate something from the essence of the film and launch into their own entity as paintings?

GM: You are referring to the interview I did for Huts Magazine in Issue 8. Some of the elements I explore in the paintings from the 2013 film ‘Stranger by the Lake’, directed by Alain Guiraudie, are discussed above. I stayed working with the film much longer than I expected because it kept offering up new dynamics between its protagonists, and an incredibly wide and deep range of the emotional tones you asked about earlier. The film takes place in a kind of Arcadian space, a cruising ground on the shores of a French lake in full summer. It shows an aching kind of alienation, both between the characters and the outside world and between each other. It presents desire, and how it can make us willfully blind to danger, and it explores how danger can be so fatally attractive. Yet it also shows acts of compassion and kindness. In its sex scenes there is a wonderful examination of how a body can unwittingly reveal inner emotions that someone is struggling to hide.

The translation from film stills to painting came about first in the preparatory processes I went through, either cropping the still or, through drawing, extending the filmic mage beyond the constraints of its letterbox format. In the act of painting that transformation was extended further through the relationship between my physical gesture and juxtapositions of colour, and what I felt was happening in the narrative, both within the chosen frame and on either side of it, before and after. It is a subtle film, with layers of potential readings, and a lot of ambiguity, and so my watching and rewatching of it was an additional element in this process of transformation; my painting process, with its many layers and corrections, served as a kind of mirror to those multiple viewings.

CBP: Other works such as ‘Green Light’ are paintings based on memory and personal experience in which you challenge yourself by not working from a source image. It could be argued that on appearance there isn’t a huge gulf, gesturally, and in the drawing, from the ones based on an image reference. Though can you talk about the personal and painterly challenges for you in this series?

GM: Yes. I think the main challenge has been one of space; I conceived of these paintings, in my mind’s eye, as three-dimensional spaces through which I was moving as an active participant. In recalling the scenes I wanted to depict I often had the sensation both of being inside the action and simultaneously of being able to see myself from the outside. So that threw up huge dilemmas of how to translate this sense of fluid, deep and involved space, along with all the other elements of physical sensation, emotion, movement, speech, and context onto a flat, rectilinear and still surface. It has felt almost perversely impossible at times. Drawing has been the other challenge; without photographic or filmic references I have had to work hard to avoid resorting to forms that are too archetypal, or too generalized. Sometimes I’ve run into difficulties with this; my ideal for these works is something not dissimilar to Tracey Emin’s recent paintings, in their visceral immediacy, and the way in which their creation is as directly as possible a mirror of the acts they represent. As soon as I get stuck in correcting some anatomical inaccuracy, I lose that feeling. Then I have to take the painting on a long and arduous journey to somewhere else.

CBP: You talk about risk taking. Can you discuss this notion both in terms of revelation in the subject matter and the risk taking in the act of painting itself?

GM: These can feel like very exposing paintings. I knew this would be so; when I began working on them, I had decided I wanted to paint from my own experience. I felt a shift, which came in large part from looking at the work of the American artists I mentioned earlier like Toor and Quarles and Langberg. They are painting queer experiences without feeling the need to disguise, or to universalize, or to explain or make accessible to a non-queer audience. I think this take-it or leave-it attitude is fantastic, and it’s where I want to be. The painterly risks I have perhaps answered in the previous question, and they exist around the lack of tangible external imagery, as well as issues of pictorial space and drawing.

CBP: The series based on a lip synch from Ru Paul’s Drag Race program feels perhaps the most volatile, fleeting and ambiguous of the selection of works here. What moved you to explore this reference and what were you reaching for in these paintings?

GM: This is the most recent body of works, and I’m still working on it. The paintings all come from one lip synch that happened in Drag Race France, Season 1. The music chosen was Le Corps, by Yseult, who was also one of the judges in that episode. It’s a moving and powerful song, which refers to the singer’s own struggle with her body image, and with rejection and self-acceptance. One of the two contestants, Lolita Banana, who is seropositive, broke down one mid-song and the other contestant, la Big Bertha, stepped out of his own performance to comfort him. It was a moment of genuine compassion and empathy and queer solidarity. I wanted to paint a kind of beauty that is emotional rather than stereotypically so in more physical ways.

I think another aspect of the images that I was attracted to is their initial theatricality. This is after all a stage, on which two protagonists are performing a ritualized ‘fight for their lives’. Even their gestures of grief are performed initially with something of the stylization of Noh drama. But then this carapace of theatre collapses, and real connection and feeling break through. Drag Race has all sorts of limitations and problems, but it has been a wonderful arena for bearing witness to our shared queer experiences. It acts as a kind of communal catharsis. It’s shocking every time to me, when we assume things are so much better, how many of us are still damaged in childhood, and need repair.

CBP: In all of these works, there is a sense of a fleeting moment, a rawness of a physical encounter. Can you discuss the notion of fleeting in your work? And in relation to the queer / gay encounter of the outsider?

GM: I think there is often a kind of questioning – What does this feel like, what does it look like, is this as it should be, and is it what I want? – as well as an encounter between role play and actual desire that all militate together to blur boundaries between bodies and minds – like dancing a quick tango in a fast spin washing machine. Whether this is a specifically queer sensation I cannot say! I think more widely, stepping outside sex for a moment, I am probably pre-occupied by ideas of transitoriness and the intensity of our encounter with the moment precisely because it is fleeting. Everything is lost and gone even as it happens. That is one of the amazing elements in Titian’s Diana and Actaeon – his death, which is a kind of dissolving, takes place unseen, in the corner of a wild wood, and you can see his hunting companions, in the distance through the trees, oblivious of his end. Only we, the viewers hiding behind a bush, bear witness to the act. For me that is what painting is, or at least the kind of painting I do. It stills the fleeting, unseen moment, and the challenge is to do so in a coherent form while maintaining that sense of instantaneous loss.

CBP: Describe a day in your studio and your approach to making a painting. How long do they take to complete?

GM: My studio is large and light. I am very happy when I’m there, but it’s also quite an austere space. I wanted it to be like that. When I arrive, I get changed, examine the works around me on the studio walls, decide what I’m going to focus on, then start painting. I then paint pretty much through the working day without extended breaks until I know I’m not mentally or physically capable of making any more coherent moves. Then if I’m sensible I stop in time and get changed and go home. A lot of the reflection I do, especially when I’m struggling to see what isn’t working in a particular painting, I do afterwards, looking at photographs I’ve taken at the end of the day.

This year, the paintings have taken a longer time than I’m used to, often months, because I’ve really been in a state of transition and a kind of taking apart of everything in a deep questioning of my language, so although I paint very fast and with a lot of physicality, the works are developed over many layers, each with the same level of intensity. I work across several canvasses at the same time, up to three or four, as I build them up, often using processes of glazing and scumbling ,and with intervening drying times.

CBP: Are there any new, current, and future projects you are working on?

GM: Yes there are. This has been as I said a transitional year, but I think next year is going to show the fruits of this work. I’m developing two curatorial projects with fellow CBP members, one for a group show and one for a two-hander, and I’m very excited by both of those. Joining CBP has been a great opportunity to develop connections like these. As a side project I’ve been thinking a lot about artistic collaboration, and what new possibilities it might generate. With this in mind I’ve initiated a series of directly to-and-fro collaborative projects. Some of these are short-term one-off improvisatory experiments in which I am working with another artist across shared canvasses. I’m also developing something potentially more complex with a French multi-media artist, based archival photographic imagery from our past lives in Singapore. Neither of us know yet what form this project is going to take. I am thinking and writing a lot about memory and past lives, and how we construct our individual narratives.

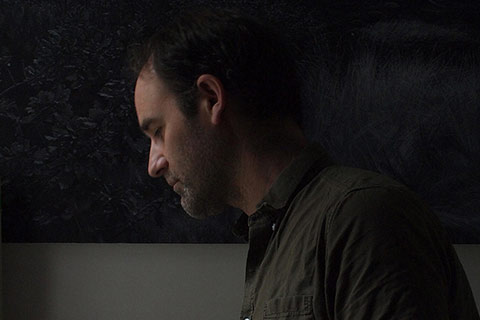

Gavin Maughfling lives and works in London. He trained at the Ruskin School of Fine Art in Oxford and at the University of East London. He has exhibited internationally, including Lounge Gallery, London, the Mostyn Biennial, MOMA Oxford, the Galerie Van Der Planken, Antwerp, the ICA, London, the Carroussel du Louvre, Paris, the Elzenveld Foundation, Antwerp and the Holland Art Fair, Den Haag.

Selected recent solo exhibitions and projects; 2023 Web Exhibition solo artist, MOCA London, 2021 The Heart is a Lonely Hunter, no format Gallery, London, 2020 between parts undone, Paintings by David Lock, Gavin Maughfling and J.A. Nicholls, Studio 1.1 Gallery, London.

Selected recent group exhibitions & projects;2022 Figure and Ground, Bermondsey Project Space, London (curated by Andrew Etherington), 2020 Beep Biennial 2020, Elysium Gallery Swansea (selected by Enzo Marra and Steph Goodger).