Geraint Evans: Artist of the Month

Artist of the Month April 2025:

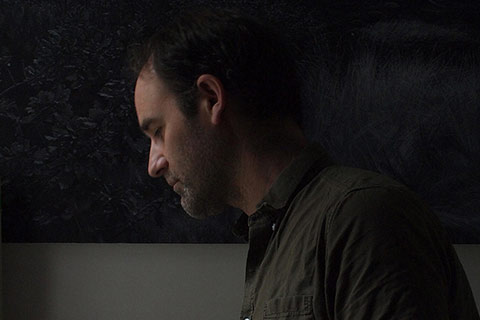

Geraint Evans, selected and interviewed by Paul Newman for CBP.

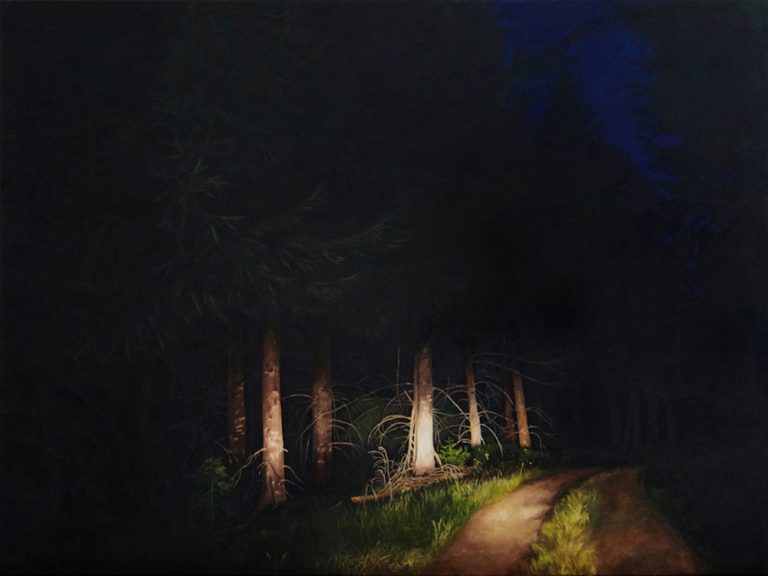

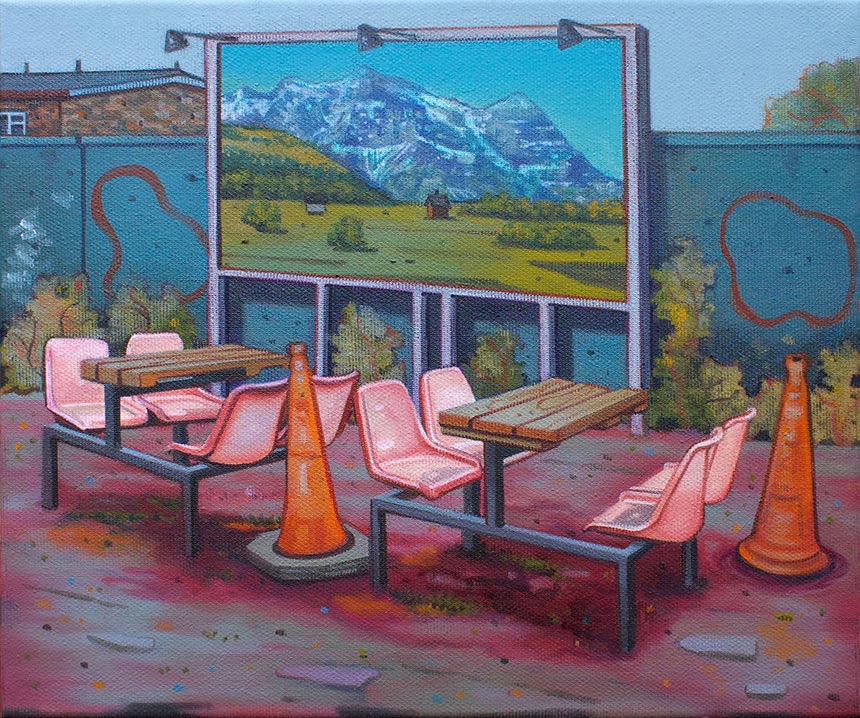

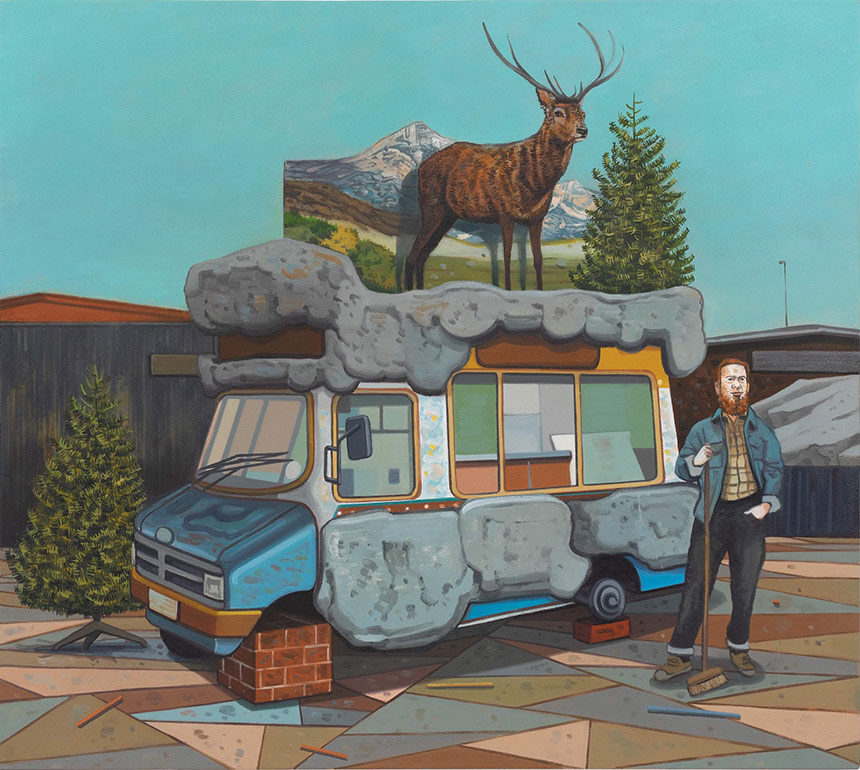

Geraint Evans is interested in the ways in which we perceive, encounter and experience the natural world and read it as landscape. His figurative paintings and drawings explore the notion that landscape is largely a social and cultural construct, responding to the writer W J T Mitchell’s observation that ‘landscape is a natural scene mediated by culture.’

We encounter the natural world in gardens and parks, in shopping malls and suburban green belts, in national parks and theme parks, as gardeners, ramblers and tourists. We see nature framed by a train window or a camera view finder. We seek out scenic views and ‘wild’ places for contemplation, adventure, solitude or as a healthy tonic. Evans is interested in both the hybridized space in which the built and natural environments meet and in our complex perception of the wilderness…

CBP: Your paintings which explore the concept of landscape as a social and cultural construct feels like a set of ideas embedded in practice for a number of years. Can you recall how this theme evolved in line with your approach to painting?

GE: I grew up in the suburbs of Swansea in South Wales, close to the Gower Peninsular and I often visited family in rural Cardiganshire during my childhood. Therefore, I was exposed to different forms of landscape from a young age: the scenic and yet highly agricultural landscape of West Wales (what geographer Stephen Tooth might describe as the Anthroposcenic), the beaches and rugged cliffs of Gower, which oscillated between spaces of quiet retreat and busy touristic sights. And the suburbs, in which the town and country meet, and where representations of nature could be seen in tidy gardens and parks, whilst the nearby woodlands that surrounded a long-abandoned railway line and brickworks provided a sanctuary for me and my teenage friends (spaces such as this have been described as the ‘edgelands’ in recent years).

In 1994, a year after I graduated from art school, I undertook a two-month residency at the Banff Centre for the Arts in Alberta, Canada, which is located in one of the county’s busiest national parks in the Rocky Mountains. I was working with a very different subject matter at the time but, during the residency, I hiked in the mountains, visited rodeos and the dinosaur museum at Drumheller and took a lot of photographs. The impressive landscape felt strangely familiar to me from tourist advertising, brochures, films and television and I was intrigued by how my encounter with the Banff landscape was shaped by my existing cultural knowledge and experiences (architects Elizabeth Diller and Ricardo Scofidio have suggested that: “often a sight must struggle to resemble its expected image.”)

I was also interested in how the tourists were managed at different sights in the park through the provision of information boards, viewing points, circuit paths, carparks, restaurants and souvenir shops. The very idea of a national park is interesting shifting between a wild space to a tourist attraction that is managed by rangers. Yellowstone, the first national park in the USA, for example, evolved its aim at its inception in 1872 from ‘a public park or pleasuring ground’ to ‘a vignette of primitive America . . . free from man’s spoliation’ by 1963.

The immersive scale of the mountains moved me, and yet I was also profoundly aware of the way landscape can be commodified and how my experiences of the natural world are often highly mediated.

A few years later, I began to use images gleaned from my photographs of Banff in my paintings – as subjects for imagined suburban amateur painters or backdrops for heavy metal hikers and nudists. I found the incongruity of these juxtapositions amusing and it encouraged me to explore the ideas first raised in Banff in subsequent work.

CBP: Looking at an early Constable painting, Wivenhoe Park, Essex (1816) it depicts a manicured country estate, and landscape painting from this area often depicted technology, like windmills, and both agricultural and leisure land cultivation. What are your art history landscape painting references?

GE: You have identified an excellent example of a painting that depicts an idealised notion of the English pastoral but in the form of a carefully manicured landscape. Wivenhoe Park was modified by landscape architect Richard Woods in 1765 and would have followed the characteristics of the English Landscape Garden tradition, in which serpentine lakes, groves of trees, grottos, gothic ruins and bridges were arranged in the picturesque style. As you suggest, Constable’s paintings often featured signs of agricultural and industrial activity and infrastructure. For example, Ann Bermingham reflects on ‘The Haywain’ in her book ‘Landscape and Ideology – the English Rustic Tradition, 1740 – 1860’, arguing that the painting’s seemingly natural setting can be interpreted as a site of production – “a kind of open-air factory” – defined by the mill, locks and quays of the river. I am very interested in the paintings of this period, which at first glance seem to reflect an unchanging, idealistic view of the British countryside at a time of great change and against the backdrop of the industrial revolution. I like the way in which painting engages with, or reflects cultural, social and political developments.

The exhibition ‘American Sublime, Landscape Painting in the United States 1820 – 1880’ at Tate Britain, 2002, also made a lasting impression on me. The scale and astonishing complexity of paintings by the Hudson River School artists such as Thomas Cole, Frederick Church, Alfred Bierstadt and Thomas Moran were very exciting to see at the time. I was also interested in the contradictions in the work – the depictions of ‘wilderness’ that were made by artists who accompanied surveyors and loggers – and their political implications exemplified by the colonial violence of manifest destiny, with which these paintings were bound up.

CBP: Can you talk about the recreational and worker figures that feature in your paintings, their cultural identities and interactions?

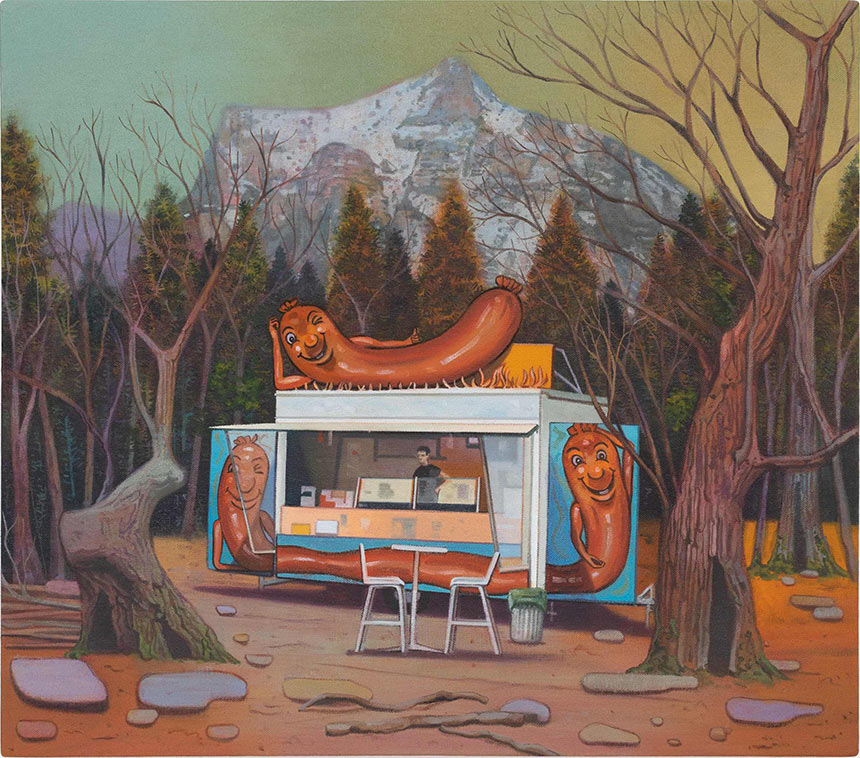

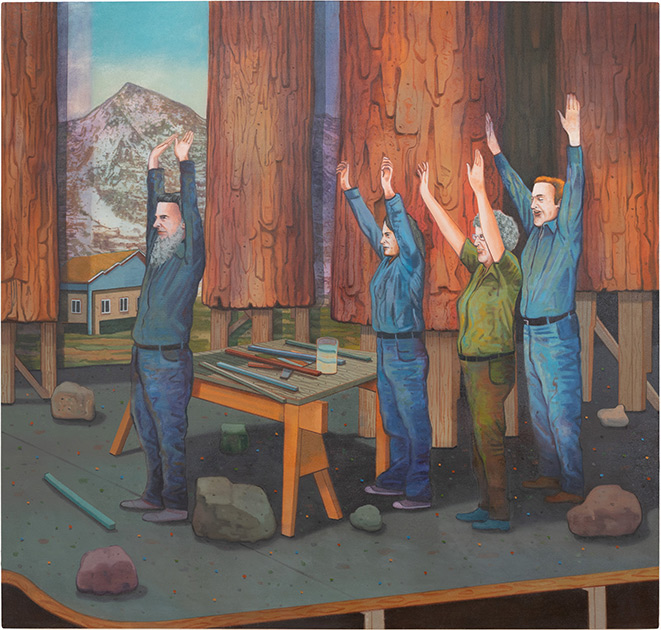

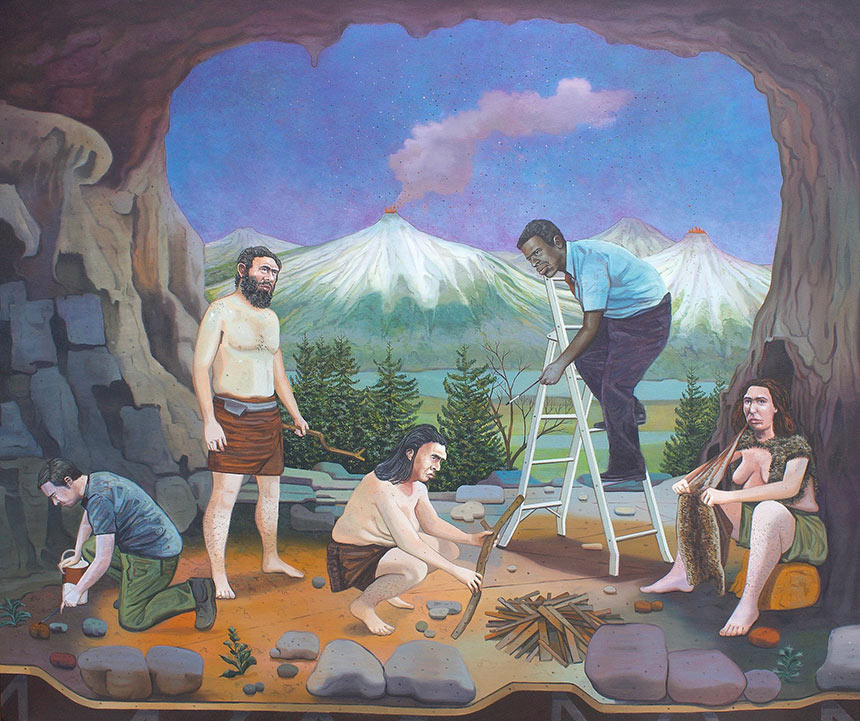

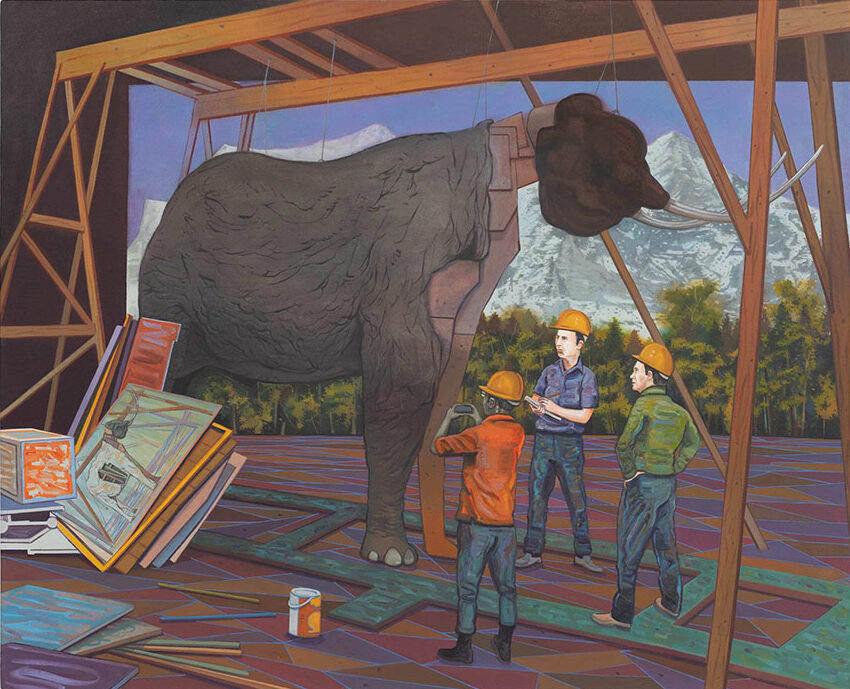

GE: The figures in the paintings are generally inventions but based on things I have seen, read about or experienced. The workers usually have creative roles – constructing or maintaining dioramas or making models and paintings. Some do more prosaic tasks, for example, running themed snack bars in ‘Monarch’ (2019) or ‘Frankfurter’ (2022). I am interested in fabricated simulacra of landscapes (seen in theme parks or gardens) and in how museum dioramas shape our perception of the natural world. The worker figures undermine the illusion of these simulacra through the seeming mundanity of their tasks. But I also identify with their creative impulses and, indeed, I often pose for the figures myself. I used to focus more on male protagonists, as I aimed to critique a certain kind of masculinity, one defined in relation to nature and landscape, but I now take a much broader approach.

Often these figures are seen alone or in pairs but there is also camaraderie to be seen in paintings such as ‘The Exercise Club’ (2022), where the four workers depicted are acting out an early morning collective fitness regime amongst the giant redwoods of a half-completed diorama.

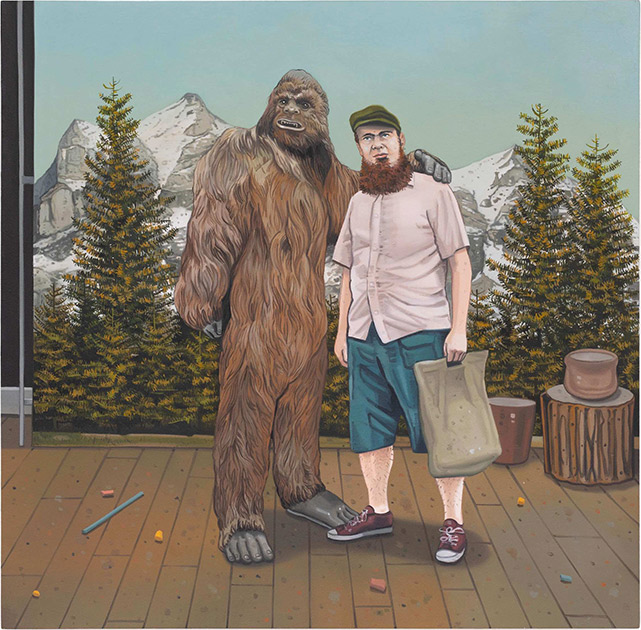

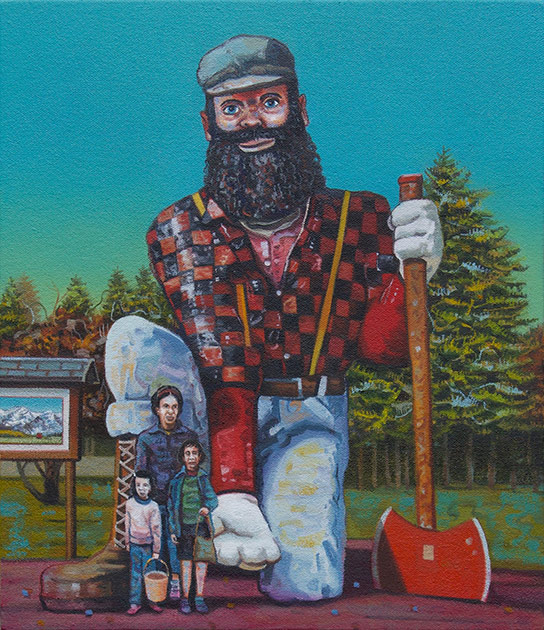

The recreational figures are usually involved in touristic activities, hiking in simulated landscapes or posing for photographs with symbols of wild nature such as bears or yetis. Umberto Eco’s essay ‘Travels in Hyperreality’ has been influential when thinking about touristic sites of nature, how controlled or fabricated landscapes, without the inconveniences of threatening fauna or an unpredictable climate, might be regarded as perhaps offering a better experience than the ‘real’ thing.

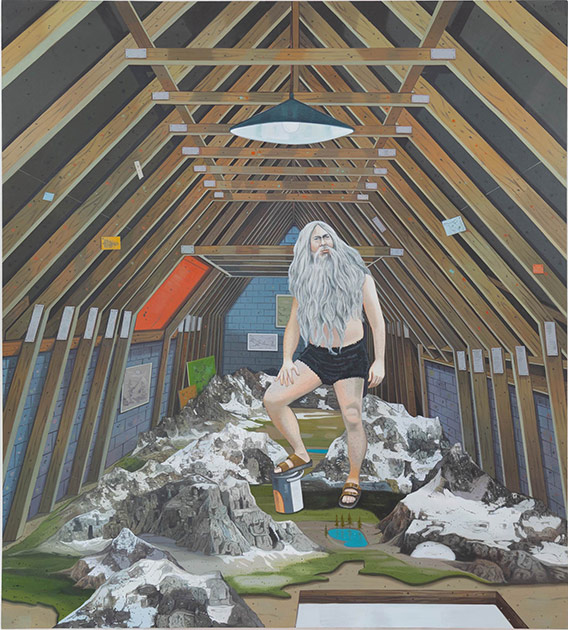

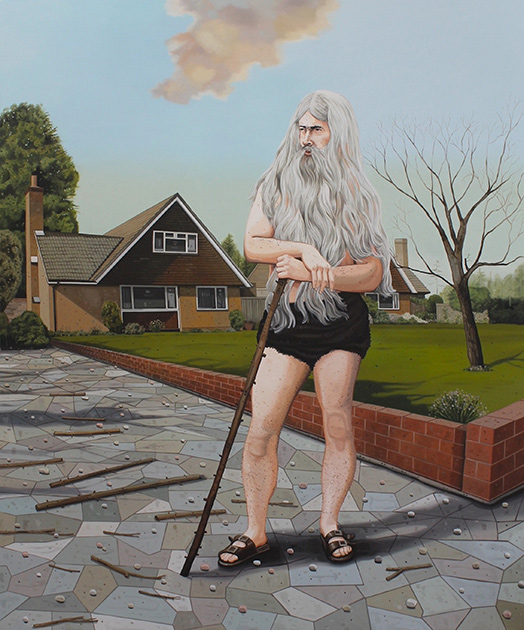

There are other figures that reoccur in my paintings such as the ornamental hermit, a curious invention of the 18th century English Landscape Garden tradition. These people were employed to live within the grounds of country estates and to appear for the amusement of the landowner and guests. If the landscape garden was to be viewed as akin to a picturesque painting, the ornamental hermit was the sort of figure that might be seen wandering the countryside in a painting by Claude Lorrain, for example.

Photography: BJ Deakin

CBP: Your paintings feel deliberately staged, like a tableau of arranged landscape, architecture and figures, can you discuss the notion of staging in your work?

GE: I have always enjoyed this sense of staging in the paintings. This is partly a result of the way the compositions are constructed, through a form of montage, juxtaposing imagery from a range of sources directly onto the canvas. The fact that there is a degree of artifice is in keeping with the broad themes of the work whilst some of the figures occupy stage-like environments. For example, the ornamental hermit in ‘A Short Stroll in the Wilderness’ (2018) stands astride a model landscape within the windowless interior of an attic. In ‘Bigfoot’ (2017), a tourist poses for a souvenir photograph with a Sasquatch before a cloth backdrop that sports a mountain landscape.

Quite a few of the paintings use the photographic or formal portrait painting pose as a compositional strategy. This inevitably creates a sense of staging as well. The reference to tourism and the souvenir is important but there is also a nod to the eighteenth-century outdoor conversation piece, a style of painting that would typically present a landscape garden with a grouping of people – usually the land’s owners – within it.

CBP: The tonal sensibility of your work feels deadpan, sometimes with a sense of the absurd. Can you identify with this as an intentional strategy, or is it more intuitive?

GE: The paintings I made in the years after graduation appropriated the diagrammatic language of the health and safety manual and something of this deadpan sensibility remains in my current work. In an essay for my solo exhibition at the Newport Museum and Art Gallery in 2012, the writer David Barrett identified the lack of fixed directional light in my work, comparing it to the deadening light of video games and shopping centres. He wrote: “almost all life on Earth depends upon the Sun, but the human species seems intent on constructing diffuse, airless environments as new homes for both itself and its replicas of selected fauna”. I think that this is an apposite observation.

However, recently I have become increasingly interested in the materiality of the paint as much as the imagery. Alongside large works, I have been developing a series of much smaller paintings and I believe that this gives me more license experiment, to work with a range of marks and techniques, exploiting the weave of the canvas to apply and remove pigment with rags, or to describe figurative forms with daps of thick paint and small, expressive gestures. I intend to keep developing these processes and methods going forward.

CBP: How do your paintings develop from drawing?

GE: I tend to make quick free-hand drawings in marker pen to work through ideas. I also make drawings in ink on paper that are more developed. Sometimes these more developed drawings form the basis of the paintings. At other times, they remain as resolved works in themselves. Drawing is a way to develop composition and narrative and to test the robustness of an idea. They obviously take less time and there are fewer decisions to make in terms of colour, scale and the range of marks employed. But the drawings do have their own characteristics, a more direct and fluid quality that sets them apart from the paintings.

CBP: Can you talk about how you build and construct your paintings?

GE: Ideas for the paintings can percolate for some time. As I previously mentioned, I usually start by working through ideas by making quick drawings in marker pen. It is important for me to have a visual reference and so I collect the images I need – either original or found. I might visit a particular place and sometimes I take photos of myself if I need a specific pose. I also have an image bank of digital pictures and 35mm slides that I can call on. I might work out the composition in a more developed ink drawing or perhaps by making a Photoshop montage.

I either project the fully formed picture onto the surface of the canvas or build up the composition, one element at a time. I trace the image in pencil – this is a good way of establishing images quickly and accurately. I work on a ground of thinly applied white oil primer on rabbit skin glue and use oil paint mixed with pure turpentine and linseed oil. I use underpainting to establish the initial form, colour and tone of the painting and then work back into it in subsequent days and weeks, using a range of marks. I often use a soft, dry brush to blend areas of paint together and glazes of colour to unite different parts. Paint is applied and removed and applied once more until what I think is a rich surface is established.

The largest paintings I make measure approx. 180 x 200cm, the smallest approx. 20 x 25cm. I usually work on 3 or 4 paintings at a time, moving from one to another.

The composition might alter significantly through the painting process and at some point, I will know the work is resolved. I keep recently completed paintings on show in my studio so that I can spend time reflecting on their success and resolution. Often, I return to a painting if it occurs to me that there is more to do.

CBP: Your colour palette has become subtly more vivid with more reds and blues, from a more muted palate of previous works. Can you talk about your approach to colour in your work?

GE: It is true that my colour palette has evolved in recent years to become more vivid and this is a deliberate choice. I have become increasingly concerned with the material qualities of the painting with the aim of using colour as much as paint to create a rich surface that will hold the viewer’s attention. I am obviously working with figuration and in response to photographic source material, but painting can shift an image into a different imaginative and emotional space and colour plays a vital role in this.

CBP: You co curated a ranging contemporary landscape painting retrospective with the late Dr Judith Tucker and fellow CBP member. How did this project evolve in relation to both of your thinking around landscape painting today?

GE: Judy invited me to give a talk about my work at the University of Leeds in 2017 and so we established a tentative dialogue about our mutual interest in landscape then. Two years later, we began in earnest to develop the curatorial project that became ‘Arcadia for all? Rethinking Landscape Painting Now’ that was initially shown at the Stanley and Audrey Burton Gallery, University of Leeds in the spring of 2023, before touring to the Attenborough Art Centre, Leicester later the same year. Our aim was to make an exhibition that asked a straightforward question: what might it mean to paint ‘landscape’ here and now, in Britain in the twenty-first century?

Judy provided the title, taken from Dennis Hardy and Colin Ward’s book ‘Arcadia for All: The Legacy of a Makeshift Landscape’, which was concerned with the landscapes of the plotland movement, a central interest in her own practice.

The exhibition explored a range of key themes: the anthropocentric and anthroposcenic; the vulnerability of landscape in the face of the environmental emergency; utopia and spaces of retreat; the edgelands and suburbia; the influence of screens and surveillance cameras; rights of access and ownership; landscape as witness; landscape and its colonial legacy. We were very aware that contemporary landscape painting very often engages with its own history.

The exhibition was deliberately wide ranging, and we recognised that there were a number of more focused shows that could evolve from ‘Arcadia for All?’ Judy tragically died during the exhibition’s run in Leicester. I learned a great deal from our conversations, and Judy’s knowledge and energy were very inspiring. I have curated a number of exhibitions now and firmly believe that they should produce new perspectives rather than prove a curatorial conceit. The process is always more productive when I work with another person with whom I can exchange ideas.

CBP: What projects are you currently working on?

GE: For my current work-in-progress, I have returned to the diorama theme, this time thinking about landscape and identity. I have been reading David Matless’ book ‘Landscape and Englishness’, and the set of the first part of the London 2012 Olympics opening ceremony has been a useful visual reference. This set, conceived by Danny Boyle and Frank Cottrell, depicts a nostalgic idea of a pre-industrial British (or more specifically English) pastoral scene – part Glastonbury Tor, part J R R Tolkein’s Shire – defined by small holdings, games of cricket and folkloric rituals.

I am the course leader for the MA Fine Art Painting course at Camberwell College of Arts and have been working on a project with the Ontario College of Art & Design University (OCAD), Toronto, Canada and City and Guilds of London Art School. The project takes me to Toronto in April to support a collaborative student exhibition.

Judy and I talked about developing our collaborative writing for ‘Arcadia for All?’ and I would still like to find a way of fulfilling the potential of our initial essay that was published in the exhibition catalogue.

I have also started to discuss a new curatorial project with a colleague, but it is far too early to talk about it here.

* Header image: Geraint Evans as an ornamental hermit

Geraint Evans born 1968 is currently the Pathway Leader for the MA Fine Art Painting course and the MA Fine Art Coordinator at Camberwell College of Arts, University of the Arts, London.

Recent exhibitions include:

2023/24 – ‘Arcadia for All? Rethinking Landscape Painting Now’ Curated with Judith Tucker. The Stanley & Audrey Burton Gallery, University of Leeds; The Attenborough Arts Centre, Leicester.

2022 – ‘Ruin’ Way Out East Gallery, University of East London. ‘The Tyranny of Ambition’ Highlanes Gallery, Drogheda, Ireland. Paint Edgy, The Ropewalk, Barton upon Humber. ‘Vitalistic Fantasies’ Elysium Gallery, Swansea. ‘Paradoxes’ Quay Arts, Newport, Isle of Wight.

2021 – ‘Imagining History – Wales in Fact and Fiction’ University of South Wales, Oriel y Bont, (coinciding with the online conference of the same name 12-13 November 2021).

https://www.geraintevans.net/

Instagram: @geraintevans_