Iain Andrews: Artist of the Month

Artist of the Month January 2021: Iain Andrews, selected and interviewed by Paul Newman for CBP.

Contemporary British Painting: Your paintings are steeped in painting history references from Renaissance – Hieronymus Bosch, Romanticism and the alien landscapes of surrealism; Max Ernst. It feels like inspirational platform to forge your own unique identity as a painter and take steps into the unknown journey. There’s a lot of instability in the work too, things in flux of the Post-Modern and Contemporary with shifting and uncertain times in the world. With these interpretations in mind could you discuss the notion of balance in your work, in terms of content and subject matter?

Iain Andrews: Balance is an interesting concept, because I think there’s an assumption, albeit a reasonable one, that maintaining balance is a more preferable state to achieve than imbalance. The painters who I’m most often drawn to, and I’d add to the names you mentioned contemporary painters such as John Greenwood and Andy Harper, and outsider artists such as Madge Gill and Henry Darger; are perhaps often on the edge of unbalancing, what you could describe as maximalists, in that the surfaces are densely packed, with the kind of detail and intensity that you get from the ornamentation on a gothic cathedral. Certainly that’s the attraction for me in Bosch and Ernst, especially in the frottages. ‘Virtually no moments of visual rest’ was a phrase that Robert Hughes once used to describe my work, and I think that, until recently anyway, that was a state that almost exclusively fascinated me. There’s a kind of frantic, claustrophobic intensity that comes from working in a small space, and both my studio and the room where I work as an art psychotherapist are physically small spaces. This inevitably translates into the methods of applying paint, since you are constantly up close to the surface of the work, enveloped and swallowed by it. The themes of my work – the retelling of imagined histories, faery tales, oral greed and transformation for example, aren’t subjects that can be observed, in the way that you might create a portrait of a particular person from life or a photograph, for example. As a consequence, if a painting ever works at all, it does so because something of this subject matter has leaked into it, rubbed off on it somehow, and the degree of this success is usually inversely linked to how hard I have tried to incorporate it. William Burrows said that you couldn’t wilfully introduce the spontaneous element, but that you could give it a chance of arriving using a pair of scissors and sticky tape. For me, the equivalent of chopping up text in the way that he did, is to ensure that I work within an environment that forces me to make decisions that would be pontificated over had I more space, more time or less responsibilities that needed attending too. The sense of being overwhelmed or consumed and of wanting to overwhelm or consume, is something that I encounter daily in my work with damaged young people, and that feeds into my image making. It’s interesting for me to notice how the hunger that you see so powerfully in many of Soutine’s early paintings, seems to evaporate somewhat in his later pieces, once he had achieved a state of comfortable living, and I think it’s possible for artists to be too comfortable, to have too much at their disposal.

CBP: You work highly intuitively and with virtuosity, juggling a range of painting effects and patinas, from varnished, cracked surfaces of historical museum paintings to the sinewy, almost virtual metamorphosing figuration that aligns with painters like Glen Brown. Could you discuss the technical aspects and repertoire of mark making? Is it a way of articulating the past, present and imagined futures?

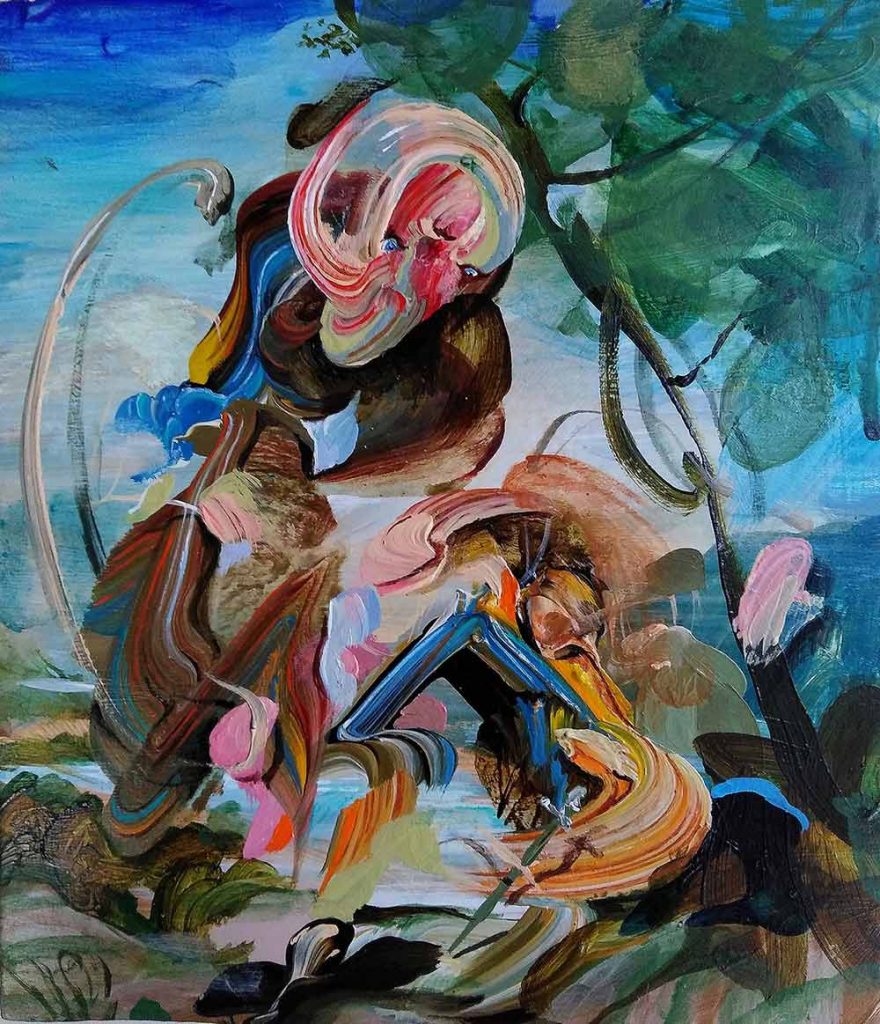

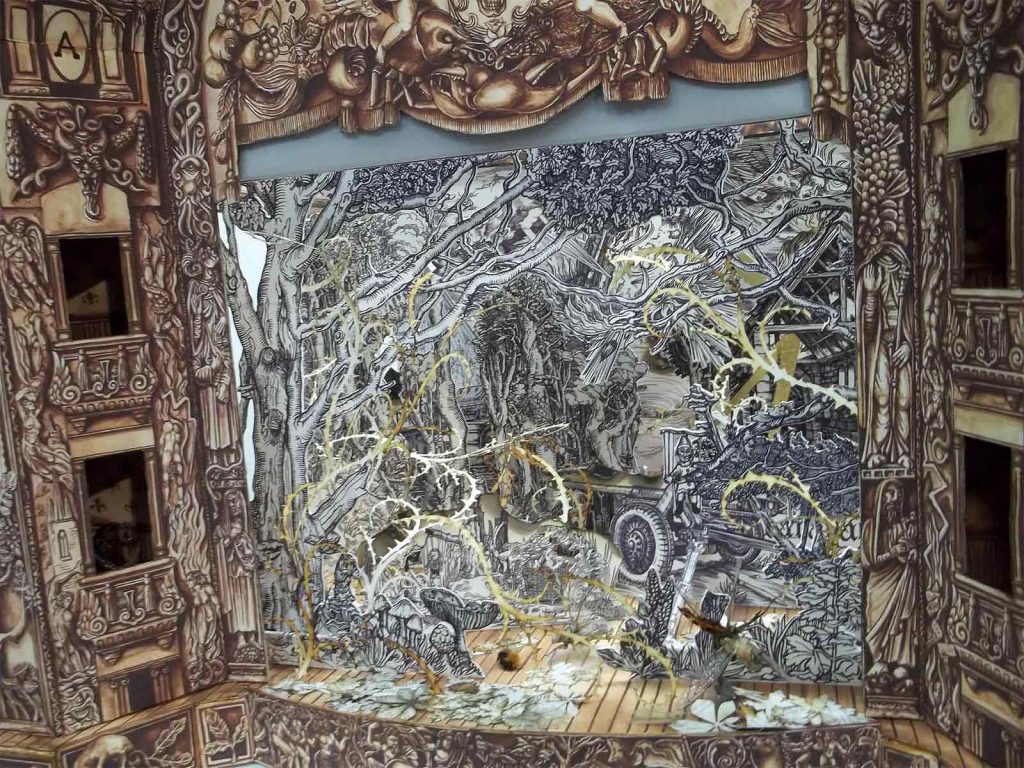

IA: Glenn Brown is certainly an interesting name to bring up, as I find my reaction to his work is somewhat double edged. There’s a huge admiration and awe for the sheer level of skill and facility in his surfaces and mark making, but I do find that I’m left somewhat cold by the image in its entirety. I’m not quite sure what he believes in, and I know that, in our contemporary climate, to take a position of uncertainty and often slightly ironical, cynical commentary is preferable to holding a deeply held belief, but it’s not a position that sustains my interest. Reading Peter Fuller and through him, discovering George Steiner, have been important landmarks in the formation of theory and idea for me. Both of these thinkers pointed towards the idea of ‘redemption through form’ – of how the making of an image could somehow attempt to compensate for the void that remained once religious faith had departed from the world. Steiner claimed that there were certain dimensions of thought and creativity that were simply no longer possible once God’s presence, or indeed the reality of His absence, were no longer engaged with, and that making images ‘as if’ there were a continuity of tradition and belief were all that might remain. I’m conscious of how the contemporary artist might seek to address this loss in meaningful ways, whilst avoiding the anesthetic distraction of the decorative or conceptual. Through conversations over time with painters such as Graham Crowley and Richard Kenton Webb, I’ve become more conscious of how the increase of choice and freedom may limit options as well as give them, and I think this works its way into my paintings through the idea of the theatrical, – a drama operating within a shallow space like a theatre or stage. Drop shadows beneath brushmarks might lift the mark from the surface, and define what may be read as a receding landscape as a two dimensional backdrop instead. I’m aware all the time of wanting to press the pause button at the point at which things move from one state to another, to hold as long as possible at the edges of becoming. A weariness sets in as soon as recognition takes place for me, Bacon called it ‘the boredom of the narrative’, and I wish to try to delay that. Practically speaking, I will usually work in acrylic paint, sanding and scraping down layers before switching over to oil as a final layer. I use a lot of linseed oil, as I enjoy the way thick paint can pock mark and crinkle, again drawing attention not to the subject but to the marks themselves. If it falls to pieces, as it often does, there’s a further scraping off and sanding down that may occur, and the image is then built up on the remains of the previous painting.

CBP: Your own statements talk about taking an art history reference as a starting point and the deviating from it through painterly metamorphosing. There is a compelling push pull between figuration and abstraction, with contrasting senses of depth, scale and illusion in the work, sometimes almost trompe-l’oeil effect of rendering three-dimensional form in a landscape. Looking at your work in progress painting exhibited for the Yes/No virtual studio exhibition for Contemporary British Painting which was a more overtly representational figurative painting, could you discuss the push pull of creating an image, ‘destroying’ it and bringing a defined figure back into the pictorial narrative?

IA: I think you flatter me with the question somewhat, the ‘compelling push’ often feels like a playground scrap with no rules. As soon as an image becomes recognisable, I find there is a need to sabotage the process somehow, destroy and rebuild it. The process of this leaves behind echoes of what went before, and sometimes these echoes suggest forms or shapes that help to move the picture forward. A recent body of works, of which the piece that was in the Yes/no show was part of, concerns the idea of the outsider, the prophet or hermit that lives on the edge of society and offers an alternative way of being in the world. The figure was based on a series of blurry photographs of a Polish tramp who lived on the central reservation of Wolverhampton ring road, whom I saw regularly growing up in the Midlands. I was and am fascinated by the ways in which his lived reality blended with the stories I was encountering in the Old Testament of Elijah, Jeremiah and other prophets whose role was to warn Israel of the danger they were wilfully entering into. The formal aspects of making these figures involved, as I’ve mentioned, acrylic underpainting, sanded, removed and reworked in several layers, followed by the addition of the splashes and blobs of oil. Although I might wish that the figure could be made up purely of instinctive, spontaneous marks, inevitably a degree of realistic copying from the photograph needs to enter into it, what Bacon termed ‘illustration’ in order to make the figure recognisable as such. The problem I often find myself with is how to unite the figure with the ground, and yet still maintain the idea that it is a three dimensional object in a shallow stage setting, against a backdrop. I think Watteau is a painter who manages this wonderfully.

CBP: One element you often pull into focus is the depiction of the eye. Its small, unsettling, and intense. Can you discuss this motif?

IA: I’m conscious all the time both of watching, and in my clinical work, of being watched. I almost exclusively work individually with young people, and over a number of years a very intense awareness of both the potency of their gaze at you, and your own regarding of them, builds up. I think the motif of the eye is an attempt to introduce something of that into the image, since it gives a recognisable hook upon which to focus, although there is certainly the danger of this becoming a device.

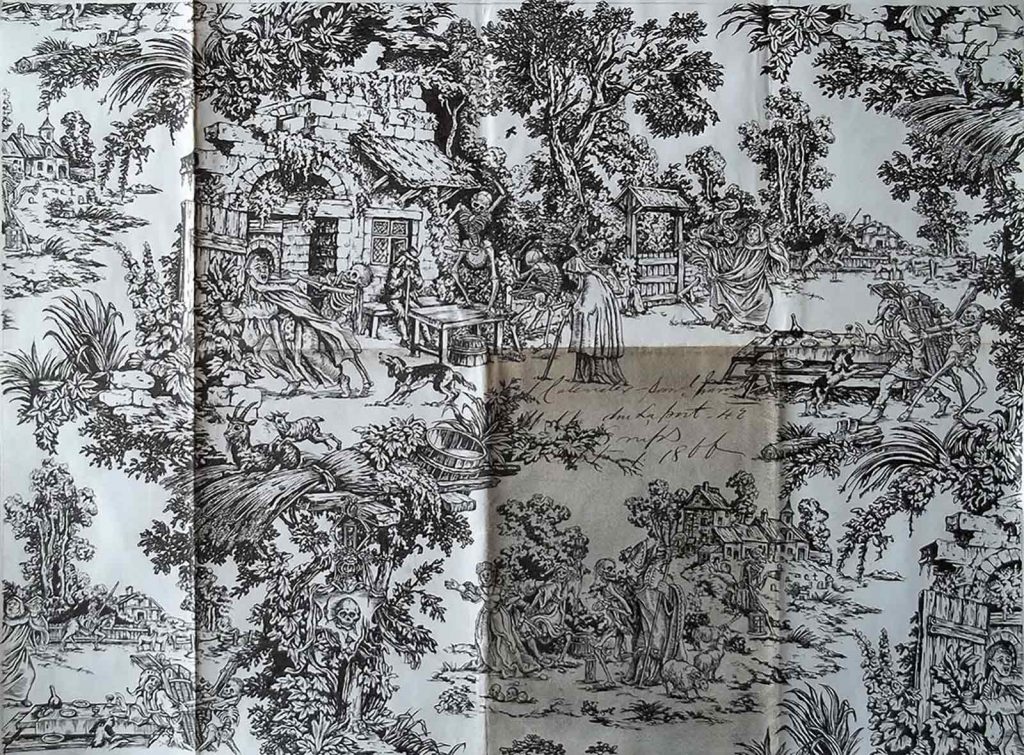

CBP: Looking at your portfolio and some of your drawing installations, they overtly reference historical etchings of religion and superstition, witchcraft, and fairytales. Your reverence to your source inspiration is implicit. They again feel they are timeless anecdotes of the chaos and fear of human history and the relationship with our environment which is current. They also incorporate mechanisms of display; etched into an antique school desk; ‘Mythopoeia – The Judicivator’ or drawn on antique paper, ‘The Nursery Rhymes of Edgar Allan’ that refer to the museum artifact, as a tablet or document to be preserved and referred to through time. Could you discuss the ideas around these works and their place in the development of your practice?

IA: These pieces operate concurrently with my paintings but have their genesis more firmly in my place of work, a secondary school in Moss Side in Manchester. I created a character who was an amalgamation of several of the young people with whom I work, who was plagued by visions of the apocalypse that he would then burn into school desks using a magnifying glass and the sun’s rays. Gradually he became somewhat of a separate entity, and the wallpaper of his nursery, his confinement and abuse at the hands of the local witch and the clay models he made in therapy became subjects of my drawing. My current drawings are made in iron gall ink, which oxidises to give a beautiful, velvety purple, and gives them the feel of being older than they are. I’m fascinated by the idea of how someone might intentionally create an object that appears ancient, the idea of weathering or ageing a piece so that it is located in a different era – the way that a model maker or forger might. I think this process is analogous to the way in which memory operates, as we age, the past becomes more jumbled and subjective, and is altered each time it is recalled.

Drawing for me has an immediacy about it that can be hugely refreshing. I keep a drawer of drawings at work that can be worked on in any few moments that I might glean during my day and this gives me a way of exploring ideas that become incorporated into my paintings. The idea of the theatrical space for example, was explored through the making of a three-dimensional drawing, ‘Il Teatro dei Leviatano’, that itself then became stage in which to compose collages to use in my paintings.

CBP: You also have a career as an Art Psychotherapist, could you discuss this in relation to the compelling psychology of your painting?

IA: I think I’ve probably answered this within the answers to the other questions as the two feed into each other all the time.

CBP: What is your regular studio routine? Do you have any systems or rituals in your working process?

IA: As a father to two girls aged 12 and 15, a husband, and a therapist, there are plenty of other demands on my time, so I tend to work in the evenings most nights, and on Saturdays, when things are quieter. History is full of painters who have struggled to find some kind of balance between family life and making work, and as I have mentioned, I think sometimes the intensity of this can concentrate rather than dilute the work, although at other times it may make travelling or taking up a residency tricky for example.

CBP: Are there any current or forthcoming projects you are working towards that you would like to mention?

IA: I am currently showing in the Trinity Buoy Wharf Drawing Prize, which will open in London sometime in January, and I will also be showing in Kyoto in January with several other painters from CBP in a show curated by Frances Woodley. My solo show in Beijing was planned for this year, but was delayed by Covid, so hopefully that will also happen in 2021, as my paintings are currently sitting on the gallery walls there.

Iain Andrews works as an artist in residence and Art Psychotherapist at Trinity High School in Manchester. Recent exhibitions include; Trinity Buoy Wharf Drawing Prize, Cooper Gallery, University of Dundee 2020, Beep Painting Biennial, Elysium Gallery Swansea 2020 ‘Angels’ James Freeman Gallery, Islington, London 2019, Personal Structures, Paper, Venice, Italy 2018. Iain has work in collections around the world including, New Art Gallery Walsall, The Progressive collection Ohio and Yantia art museum China.