Joanna Whittle: Artist of the Month

Artist of the Month February 2022:

Joanna Whittle, selected and interviewed by Paul Newman for CBP.

‘The subjects of Whittle’s paintings often take the form of ruins and re-evaluate how these operate in contemporary settings. They explore romantic motifs whilst depicting modern structures with fading sherbet colours and acidic electric lights. Through an enquiry into picturesque themes the paintings push to the edges of these romantic reflections in order to understand their undercurrent in contemporary landscape painting…’ read more.

For February’s Artist of the Month Joanna Whittle discusses the evolution of her painting, the Forest Shrine series and the Heavy Waters project at Site Gallery in Sheffield 2021.

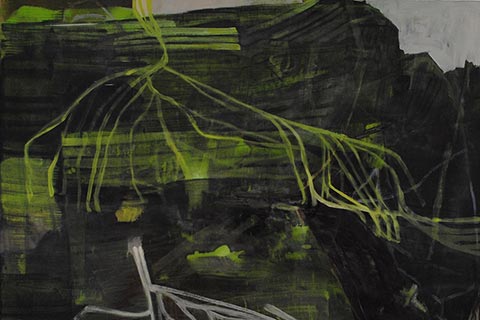

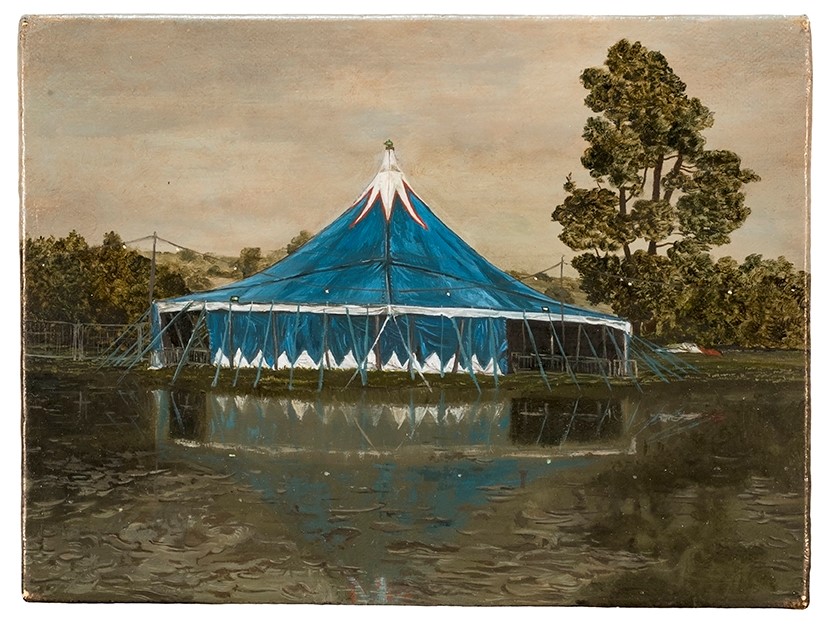

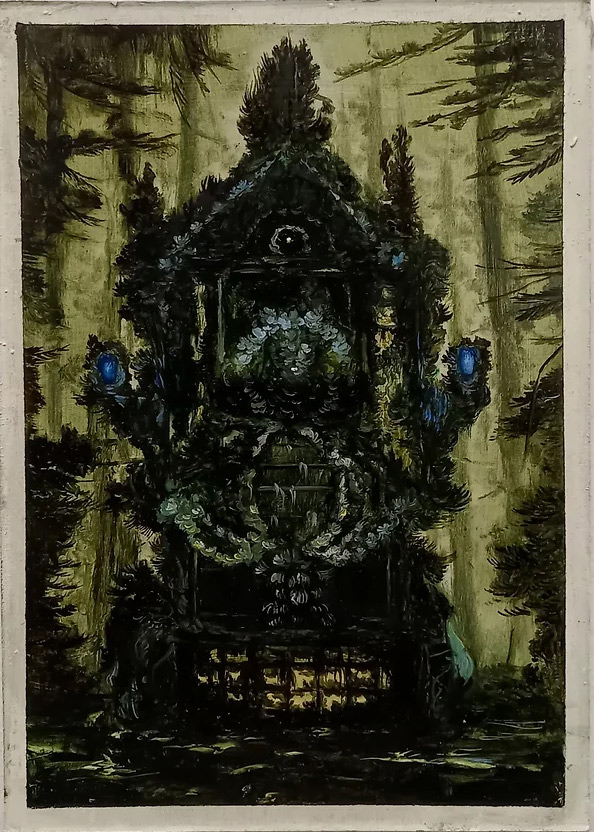

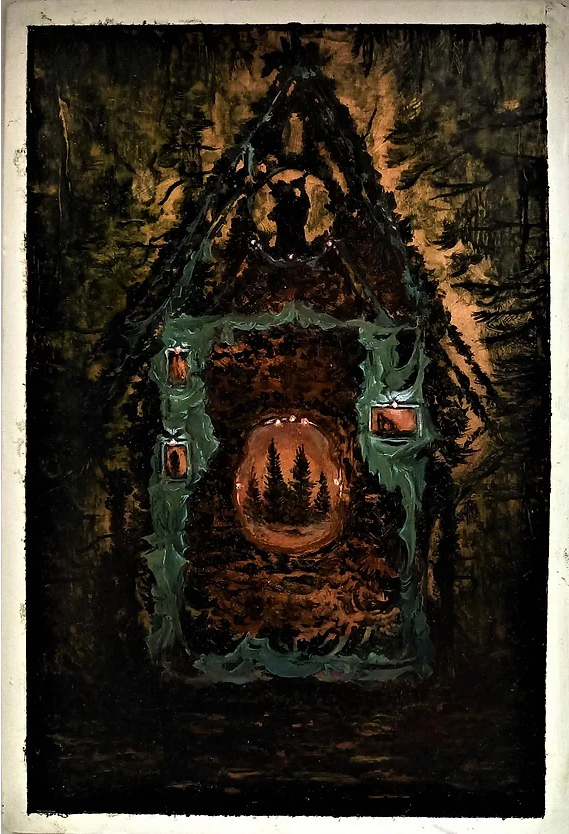

CBP: The paintings Sorrowing Cloth and The Machine depict seemingly dilapidated and ornamental structures in muddy twilight or pre-dawn landscapes. They have mutated from earlier more straightforward depictions of tent structures in flooded land which had a surreal edge but have evolved further into fluidly unstable and dream like constructions. Can you talk about the evolution of the imagery in your work, where it started and the journey it is on?

JW: The work has gradually been evolving since the earlier more traditional landscape paintings such as ‘Rain Tent’ (2017) which nevertheless were still not straight landscapes but those subtly tweaked and pulled out of place by a layered displacement.

‘The Machine’ was made on the cusp of the first lockdown during late nights in the studio and as the world around was gradually falling silent, so the structure sank further into the mud, reflecting this creeping sense of fear, becoming more unfettered from reality. ‘Sorrowing Cloth’ was made in the thick of lockdown and seemed to reflect this time of pervasive mourning, and loss, a strange bereft tent in a drowned world, flourishing with memorial flowers. I have long been inspired by memorials as strange sites of unseen activity, where flowers appear and gradually fade only to be reinvigorated again during times of remembrance. The shrines emerged in the winter in our second lockdown and seemed as if to limp out from the forest, almost as a precipitation of this accumulated darkness.

In retrospect the recent period had a large impact on the work and its evolution, not least in the lack of my usual source material as I could no longer photograph fairgrounds. The work turned inwards as reality became more intangible and the paintings which emerged seem to inhabit this half world.

The tent as a motif is a strong one and I think of them more as a methodology of painting beyond their subject, they are part of a language representing a fragility and a transgression of boundary which defies certainty. So, in as much as the painting stays fluid in the making so does the fragile membrane of the tent which is defined only by its temporariness.

CBP: The liquidity of these works and the slippage of mutating forms could be linked to the fluidity of paint. To what degree is the evolution of the work led by the natural development of your painting technique and signature style?

JW: I think there’s a very obsessive process in my style of making work both in terms of the meticulous detail but also in the layering. I always keep the paint wet and whilst I build layers, so these remain malleable, enabling me to work back into them, pulling earlier layers forward. There is a state of flux in both method and subject matter where structures sit in fluid, flooded landscapes and hover between stability and collapse, between purpose and decay as the landscape (and painting) absorbs them.

The shrines represent an accumulation of activities and I think the painting and the structures depicted are part of the same dialogue. There’s that beautiful moment in their making where there becomes no divide between the materiality of the paint and what’s been depicted, and I love that almost somnambulistic feeling when making work. The surface falls away and you are embedded in that world and that too, is the space the viewer inhabits.

There’s a strange feeling also when this journey comes to an end and the paint is allowed to dry. It’s quite an emotionally strange moment when I take the paintings out of boxes or see them in exhibitions. They’ve become themselves through this drying, independent of me, they’ve become ‘other’ as they go on into the world, the paint has stopped moving and the moment freezes.

I think it’s worth noting that when I begin the paintings, I have no intuition of what they will become, beyond a certain structural beginning which in a sense is the marking out of the arena where the enactment of the painting will take place. There’s a certain point, usually midway, where the painting seems to become autonomous and I have a strange sensation of it looking back at me, of being watched. Sometimes I turn them to the wall, not so much to pause the dialogue, but more in the way mirrors are turned against a wall lest someone should walk out of them. This is when I feel it slips most into darkness, into its nadir, before the painting emerges and reveals itself. The darkest hour is before the dawn or before tiny daubs of paint cast light upon dark water.

CBP: The wildly rococo like structures in the paintings have an ornateness with a hint of Faberge, could you discuss possible influences such as Rococo?

JW: I like the idea of the paintings being like a Faberge egg and there is indeed a kind of jewel like quality to some of the paintings, particularly in paintings like ‘The Machine’ but also generally in terms of the painting surface. They have a strange kind of patina as a result of the layering that becomes almost velveteen in the peaks and troughs of the surface and how light reflects upon them and tiny shadows pool. I have always been fascinated by how paint can act both illusionistically and structurally, existing between the material and the hallucinatory.

with varied fabrics and fabric flowers, overall 95 cm x 52cm x 14cm approx., 2021.

Photo: Jules Lister.

‘The Machine’ is based on a ‘wave swinger’ which is a traditional piece of fairground equipment which kind of rises up out of itself in this odd and disjointed movement, like an automaton, and then rotates in ever increasing velocity. They are always adorned with these rococo insets depicting faraway and mystical scenes, all glittering and frenetic with flashing lights, constantly oscillating. They are simultaneously terrifying and romantic rather like the fairground itself. So, I think this acts as a source in my work. But again, in the paint handling, this retreats back into the landscape, where this fluid style of mark making can describe leaves and rock and wood with the same touch so they almost flow into each other. I think this rococo flourish is almost a perfect method of embracing these chimerical interchanges between the physical and imaginary; where wood or stone eddies and pools into something other than itself; all under the glimmer of an acid green bulb.

CBP: When you are working with ceramics, how connected is it with your painting process in terms of making sensibilities and as problem solving?

JW: When I work with ceramics there is a whole different language to engage with and yet I do approach making ceramics as a painter. I don’t have a studio process when making ceramics and each object I make becomes unique in itself rather than being part of an on-going studio practice.

The objects are both separate from and informed by my painting practice. They somehow fill this gap between my paintings, which have become so intensified and visceral so that everything flows away from this tiny brush point, and clay which gives an innate thud as you put it down before you. It asserts itself through its cultural history but also through the continuity of its particles; it has always been and will always be. When I use clay, I know it has been through many hands before mine. There is this wonderful coldness of it and how it warms and dries at your touch. It’s very intimate. The making processes are so complex and also so subject to a complete lack of control through the firing process. An elemental flux.

Considering my process in painting, the procedures of ceramic making, which burn and harden the material, precluding any revisions, has been an interesting adjustment, an almost opposite transaction. And yet as a painter I choose processes where glazes sit inside glazes, and the line floats within an acquiescent surface. I imagine this soft sinking of line within the kiln, a drawing being fired into a tin white glaze at 1200°C

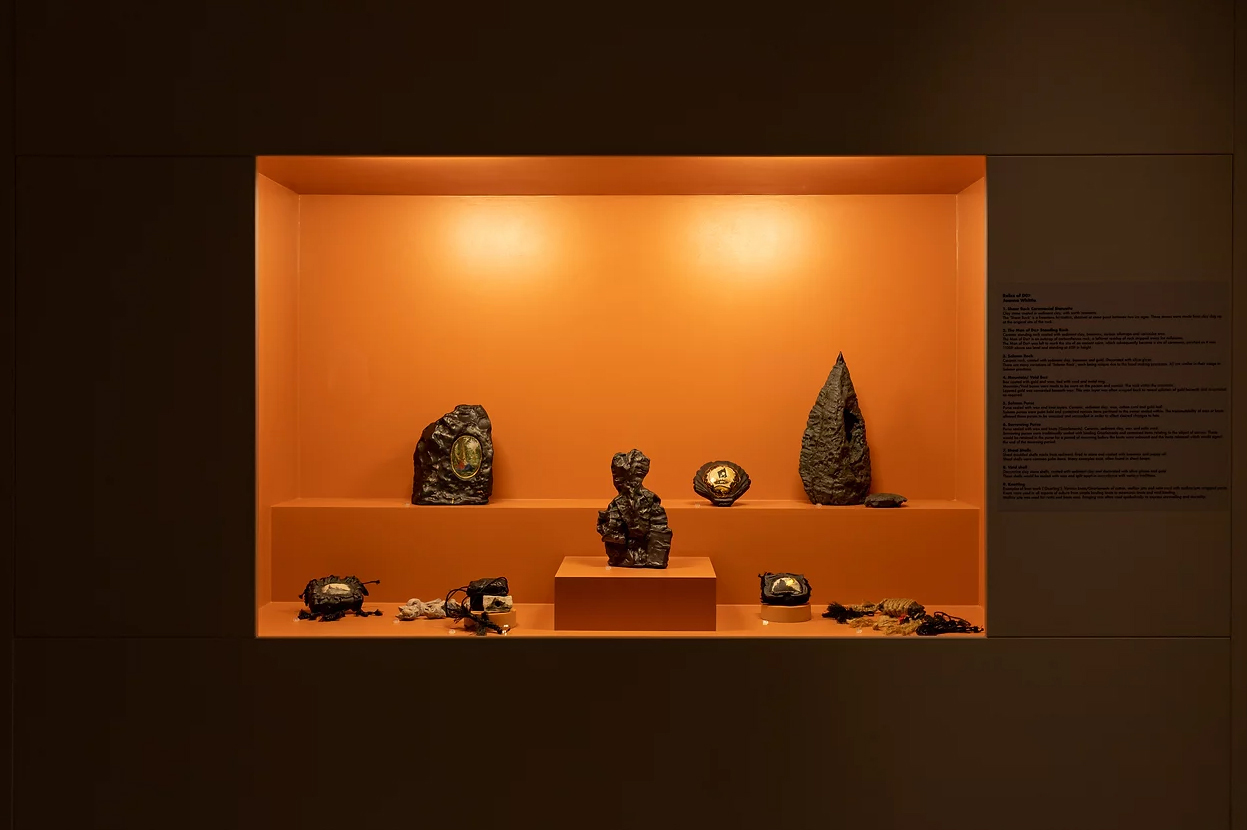

Platform 20: Heavy Water, Site Gallery, Sheffield, 2021. Photo: Jules Lister.

CBP: You have taken part in ‘Heavy Water’ at Site gallery exhibiting some of your ceramics. Could you discuss the mechanism of display and ideas of the museum artefact in the development in your work?

JW: Taking part in the exhibition ‘Heavy Water’ was an interesting part of the development in how the work is shown. In 2020 I received Arts Council funding to work with the Portland Collection on the Welbeck estate and through this I really began to consider display and how the paintings could sit alongside the ceramics holistically. It became obvious to think of them as a collection rather than trying to make them communicate with each other. In this they maintain their own integrity yet inhabit the same space. In ‘Heavy Water’ the ceramics occupied an illuminated display case whilst the paintings sat hooded in self lit shrines, in a vast, darkened space. The shrines crouched over them, almost like the structures in the postcard paintings. And yet within they were lit like gaudy shrines or fairground rides, an almost perfect symbiosis of content and display. The ceramics as unique objects become artefacts, relics of unknown cultures and are exhibited with museum labelling to authenticate and engender these imagined histories. I am very interested in how museum display directs narrative and subsequently the perception of objects. And as artefacts they seem to step out of the discourse of ceramics, they become these unique objects of residual touch and ritual, adorned with string, coated with wax and slippery with graphite. In the imagination they have been made and used, interred, and unearthed and it is through this imagined process, implicit in their display, that they become other than the simple process of their making.

CBP: You are concentrating increasingly on painting miniatures, for example The Shrine series. The ambiguity of scale is compelling in different ways; from the encounter with the original compared with a reproduction online or in a book to the sense of a monumental structure when looking into and journeying through portals within them and into the landscapes they are situated in. Can you discuss the notion of scale in relation to how the viewer might navigate the work?

JW: I have been working on a small scale for many years, yet the shrines inhabit these small handheld, postcards, almost like objects and much smaller than the paintings on canvas. I love the paradox of space in the miniature, how they act as portals, expanding outward to unlimited space in the imagination. There is a sort of tacit pact between the painting and the viewer, agreeing to embark on this unravelling of space, an intimacy where minute structures suddenly become vast in the mind and tiny descriptions in paint evoke smells of wet mud and just fallen rain. As such, photographing my work and presenting it digitally seems always to frustrate, where the paintings stretch and distort as their scale is expanded on a screen and they lose this elusive dimension of the imagined and also the material.

I am really interested in the lure of the miniature, the way it beckons you across a room; for you cannot know if from a distance, and in that move the relationship is already made, you are being made implicit in its secret. All of these movements, these physical inflections of peering into tiny spaces, of drawing closer to the mottled surface; all of these are lost in the splayed-out digital image.

Space and scale also operate differently in the work. The tent paintings seem to sit in these uncertain spaces which recede into the landscape and the viewer enters them through that traditional landscape relationship where the viewer stands vertical, and the landscape lays itself out on the horizontal. The shrines on the other hand, stand facing you in a portrait format. There is much more of an encounter with this physical and embodied ‘otherness’. They do look back, whilst around them space closes in as dark branches push against the painting plane and reach into the frame. One feels surrounded by this forest, by its darkness and pine smells.

CBP: The Shrine series are painted over postcards. What were the source images, and how did they influence the paintings on top of them?

JW: For the postcard shrines I buy batches of second hand cards so I have no idea what will be on them. Some are too beautiful to be painted over and end up being added to my ever-growing stack, sometimes becoming source material for paintings. The selection of those to be painted on is determined, strangely, by touch. I like the way they feel in my hands, the lightness of them and their parchment paper surface, like soft skin. I like the patina of time in their touch and the way they gain a weight through the painting process, which is noticeable when you lift them again. The ephemeral gains gravity through the intricate laying down of paint. There is a strange precipitation of enactment here. It’s almost the converse of that idea of the body becoming lighter in death as the soul departs, it’s like a process of reembodying.

In practical terms the card must then be prepared and adequately primed to create a stable ground for the painting which obliterates the image. Occasionally, however, words may be left to remain at the painting edge and often the reverse of the postcard will be written on. I love reading these brief missives, of words becoming whispers through time, some with plaintive entreaties (‘please do visit soon’) but more with talk of weather. So, the images and the words on the postcards do not become direct sources but it is in the process of making, this layering of history in which they become integral. Almost like ruins themselves where history becomes overgrown and derelict yet glows beneath. It’s akin to the processes in all my paintings where a painted ground (or copper) glows beneath, but with these postcards the content forms part of an uncertain ground. Occasionally too, the words and place names may be woven into the titles of the works in an echo of their history.

CBP: At this stage in your practice to what degree do you utilise source imagery as a referent and what degree do you rely on memory, intuition, and imagination?

JW: I think its source material is quite an interesting consideration and we touched upon it when spoke about the earlier works with sources of dusk or dawn lit fairgrounds and circuses. But even these direct source images were collaged within the paintings, with tents being displaced or the time of day being changed, easily darkening a summer morning with muted greys.

So, with lockdown this source material was either lost or changed and there are many times now where I can spend many hours with a painting and not refer to any source material at all, which leads back into this eddying of thought and shimmering of reality. However, they do always pull back into reality and there are always aspects of minutely observed detail in the work. The sensation of reality must be sustained in order to make the imaginary credible.

There has always been a phenomenological aspect to the work too, and they are as much about perceiving and inhabiting space as they are about this visual unravelling. Which is why they are always unpeopled, as the viewer is the only perceiver, yet with a sometimes unsettling feeling of being watched by something unknown, something hidden. With this collaged method there is a certain amount of construction within the paintings, where structures are painted and then the lighting is added; ropes are tied down and stays are put in place. Sometimes it feels more like a very small engineering project. And the shrines are completely constructed from different elements, giving them that that chimerical nature.

With these methodologies I always have the Surrealists’ ‘Exquisite Corpse’ in mind, this splicing of elements so the embodied form freezes and ossifies. This frozen moment captured, yet as always with these paintings there is a sensation that at any moment a twig could crack, or a leaf be pushed aside.

CBP: With regard to the Heavy Water project as an example of diversifying your making and installation strategies are you continuing in this direction with your own work and your collaborative projects?

JW: Yes ‘Heavy Water’ was an exhibition which I took part in during a residency with the Freelands Foundation, based at Site Gallery in Sheffield. I was exhibiting alongside two artists, Maud Haya-Baviera and Victoria Lucas, who make work very different to mine in film, photography, digital media, and sculpture. Yet there was such an undercurrent of overlapping themes between our practices; of motile landscapes and our presence within and without of them, the traces we abandon and incur and in that which we take and that which we leave. Their work is also meticulous and layered through very different processes to mine and yet there is an analogous approach to this making even down to the layering of images in a collaged approach. So not only did the works inhabit the same physical space they also seemed to inhabit the same emotional and cultural space and through their interaction defined the topography of a fourth world, an additional contributor in the exhibition. I am continuing to work with them both on upcoming projects as we have subsequently formed the ‘Heavy Water Collective’ and will be embarking on a research project later this year.

I am definitely interested in these collaborations between different practices as I feel painting can often become more itself in these interactions and considerations around framing and display in these other terrains can bring up interesting considerations as to what this means in the perception of the painting. But equally, the dialogue within the painting world, painter to painter, represents a uniqueness. Only painters ask the questions painters ask whilst thinking about this fluidity of pigment being smeared around the flat surface, brush mark by brush mark in a sort of hand-to-hand combat.

About the artist

Joanna Whittle’s recent solo projects include; The Mitre Owl, Ongoing collaborative project with David Orme an evolving collection of artworks, artefacts and ‘object perdus’, first exposition held at Artcade, Sheffield, 2021. Between Islands, Arts Council funded project (DYCP) working with the Portland Collection and the Welbeck Estate, Worksop, culminating in a final exhibition at the Harley Gallery on the Welbeck estate, Nottinghamshire, 2020.

Recent group shows include; New Light Prize Exhibition, Tullie House Museum, Carlisle. Silent Disco, Curated by Graham Crowley, Greystone Industries, Suffolk. Heavy Water, Site Gallery (Freelands Artist Programme Residency), Sheffield.

Joanna Whittle was the winner of the New Light Prize, Valeria Sykes Award, 2020 and the Contemporary British Painting Prize, 2019

Links: