Molly Thomson: Artist of the Month

Artist of the Month October 2021: Molly Thomson, selected and interviewed by Paul Newman for CBP.

Molly Thomson’s work concerns the performance of the painting as an object, using the conventional painting panel as a springboard for action and a vehicle for thought. She is interested in conditions that confine, resist and limit, and in what happens when those given conditions are subject to question and boundaries are breached…

Contemporary British Painting: Studio residues appear to be a narrative in your work, stuff in the periphery in the studio space, works in progress, materials and apparatus, manipulating and embellishing found objects. Perhaps there was a lightbulb moment earlier in your career, and this theme that has remained embedded in the work? Would this be a fair assumption as a viewer?

Molly Thomson: I’m not sure about lightbulb moments, but it’s interesting to discover that some of the roots of your concerns were there decades ago; it’s just that the diversions in the road you take can make you forget. I went to art college assuming that I was going to paint, but suddenly side-stepped this option and specialised in sculpture. I think this temporary working habitat began a process of re-framing what painting could be for me and by the time I finished at Edinburgh I was making relief painting/constructions that sat in real space but hinted at interior spaces.

My current work really has its beginnings about 15 years ago after a period of wondering where I was going. I was reading A Journey Round my Room by Xavier de Maistre, which pointed me towards Georges Perec and the Oulipo group, and this led to ideas of working with where I was and what I had around me. I archived the debris in the studio, I recorded photographically and through text and I made temporary objects. I found that reduced means, simple (if provisional) rules and working with what was there or had “failed” or been cast aside liberated me from paralysis and gave me a new focus. It felt more like play and gave me the courage to trust a process of thought that advanced through a series of small acts of attention.

The studio continues to be a site of speculative construction, accumulating residues and repurposed objects.

CBP: Many of these works go much further than just embellishing found objects, there’s a real nuanced complexity to the way they appear cut apart and reconstructed, over and over again. Can you talk about the notion of complexity in your work, perhaps in relation to minimalism?

MT: Despite the fact that I use the most basic of forms and structures – and I would allow that they might give a nod of acknowledgement to minimalism – what interests me in the end is the capacity of things to go off-piste and present me with something quietly problematic or playful. If this is anything like minimalism it is a minimalism that has become hybridised with other things and might therefore suggest multiple identities or behaviours. However, it’s true that the processes that these quite modest painting/objects go through is often in the end more complex than might be evident. The shifts and alterations result from changes of mind and consequent repairs, sometimes over quite an extended period of time. They are not things that swagger or proclaim. They are pared down and probably a little reticent. They can be made, unmade and made again, differently. I try to pay attention and work out where to take them. It’s about doing more with as little as possible.

CBP: What are the starting points for the works? Do you have several pieces on the go that play off each other, talk to each other to help problem solve the next step?

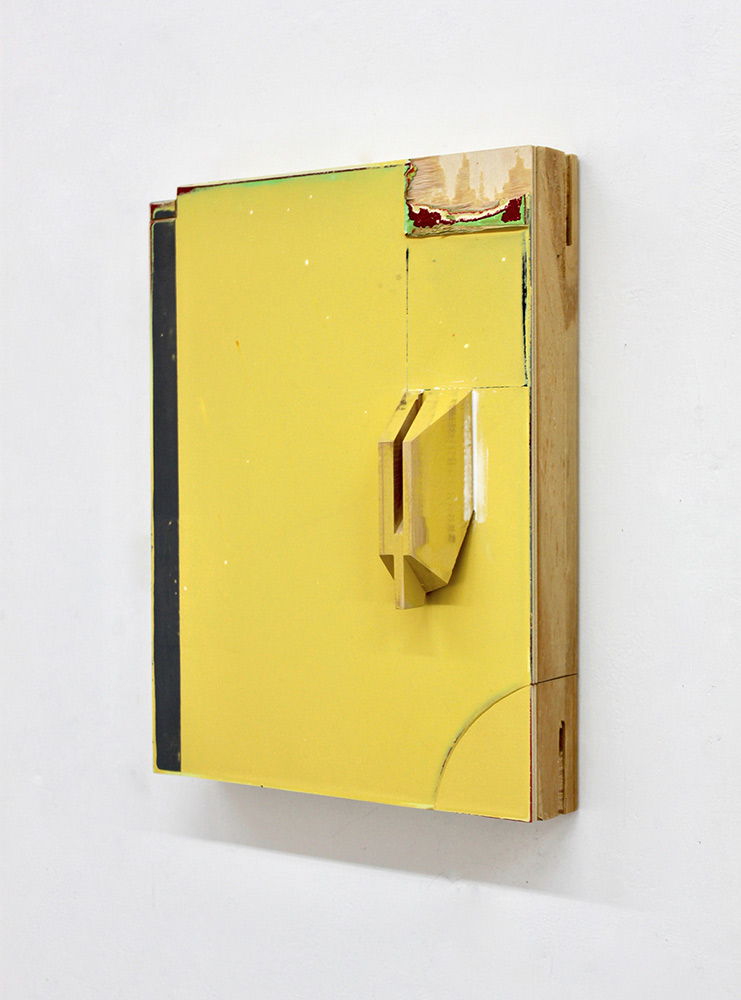

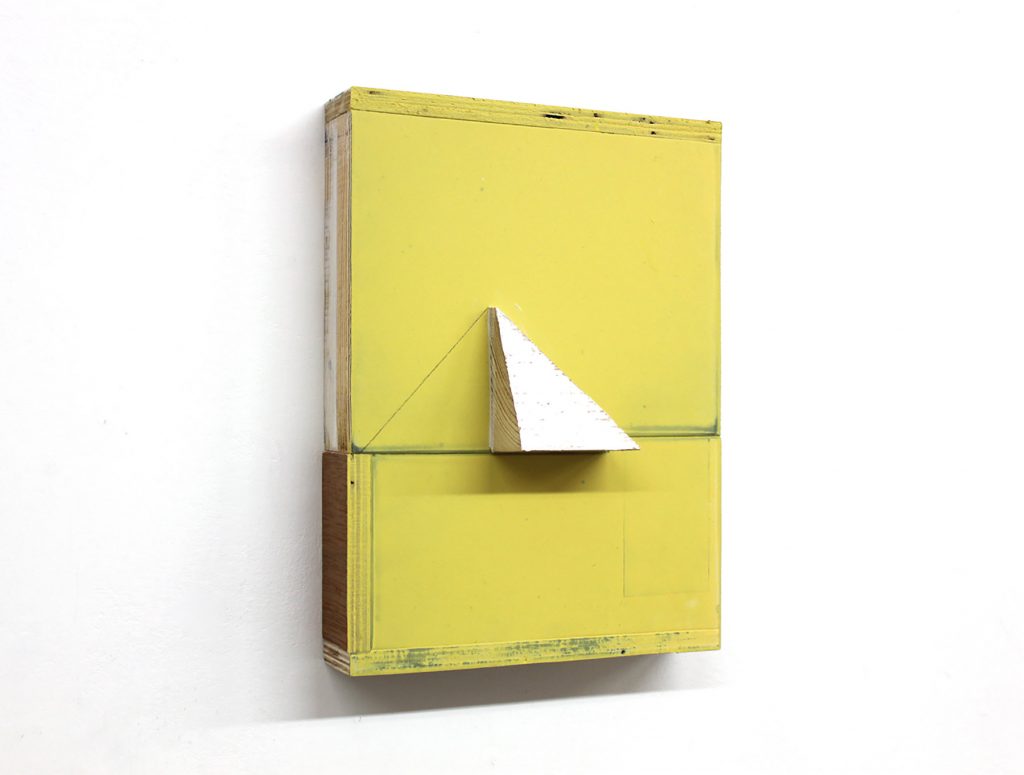

MT: My work often begins simply with a small rectangular panel which I have put together using a rough ready-made stretcher whose flimsy canvas has been replaced with MDF. This provides me with the most basic of starting points while taking me a step towards engaging with the piece as an object that inhabits space. The direction a work will take is the consequence of a series of cuts or displacements that alter the centre of balance and provoke a problem to be solved. Occasionally the cutting is drastic and emergency measures are necessary to maintain the structure. I often have a number of small pieces on the go at the same time and they can play off one another, through their similarities or differences. I am interested in the conversations they strike up, either with each other or other objects lying around the studio. Like conversations they can come and go. I find the idea of provisionality or temporariness quite attractive, though it doesn’t stop me from attempting to achieve a kind of precision or poise.

Although I am talking here about a developing conversation with the work itself, I continue to take photographs, to look at objects and their relationships (largely in a human-made context). Indirectly, this kind of looking feeds my thinking.

CBP: And at the end, what are the finishing points? Do you exhibit ‘finished’ work and later rework it and even hybridise works?

MT: It’s hard to describe a finishing point. It’s a point at which a piece is doing something that interests me, and when continuing to work on it would just be tinkering. However, I do occasionally completely rework pieces that have been exhibited and it is true to say that anything that comes back to the studio can be fair game after a while. There’s a great satisfaction to be had in re-starting a conversation or realising that a particular one has ended and I am at liberty to reconfigure the material. My studio is packed with supposedly finished work as well as rejected fragments and it is out of this collision of old and new phases of thinking that new possibilities arise.

CBP: There’s something about excavation in the work; stripping back and something that implies behind the scenes and stage set props. This is pertinent in sliced works on castors like ‘Companion piece (mobile object with a closed interior)’ and canvas works like ‘Blue with aperture.’ A fundamental aspect of painting can be about erasure or removing layers as much as adding layers. Could you talk about this aspect in the work?

MT: What you say about excavation is relevant in different ways. When I cut away and remove or reorientate sections of the panel’s facade I often have in mind the fictional stage of painting as something with a hinterland that is generally “behind the scenes”, out of sight. Sometimes, when the whole structure is split and folded in on itself (as in ‘Companion piece (mobile object with closed interior)’) the behind becomes the “inside”. It seems important that what can’t be seen is made present in some way, but whether the process is one of enclosing or opening need not be spelt out.

Talking about opening and closing and paintings experienced as layers makes me think of Renaissance polyptych paintings with multiple hinged panels that can be moved to reveal or enclose, reminding us at the same time that the images sit on structures with fronts and backs. It’s also hard to avoid associations with archaeology when talking about excavation and although it might be stretching it too far to talk about it in this context the fact that I studied archaeology as part of my degree just maybe left me with a residue of interest in both the methodologies of such meticulous probings of surface and the question of what lies out of sight.

However, as you say, the adding and removing of layers is a fundamental aspect of painting and both these processes contribute to the physical fabric of my work, not only in terms of paint, but also in terms of the other materials that are added or subtracted.

CBP: Talking about a recent canvas work like ‘Blue with aperture’, after the first glance you realise the revealed stretcher bar is in the wrong position, it appears rearranged, implying nothing is quite as it seems behind the scenes. Can you discuss the notion of artifice in your work?

MT: I’m not sure if a degree of artifice isn’t implicated in most art, but if the word implies a trick or pretence of some kind this wasn’t the intention. My initial thought was simply to look for another way of breaching the panel’s edge, and by cutting the section out and reversing it I arrived at something a little more interesting to me than I had anticipated. The rearrangement that takes place in this piece does seem, unlike other reconfigurings, to provoke the sense of a logical glitch or an illusion of something else going on. Flipping the corner to the top of the cut gave the curious sense of another structure peeping out from inside. So maybe it’s true, nothing is as it seems behind the scenes…… Then again, even if the displaced corner weren’t enough to make you look again it occurs to me that the surface of the exposed stretcher is completely flush with the rest of the surface so it behaves almost like a painted image despite the real space it encloses.

In general, though, I think that the strategies of displacement and reconstruction that I use are pretty straightforward. I tend to proceed from one step to another, making changes and responding to what happens without a predetermined conclusion in mind. As long as the baggage I carry from past work remains useful and interesting it feeds what I do next, but trying to calculate outcomes rarely satisfies.

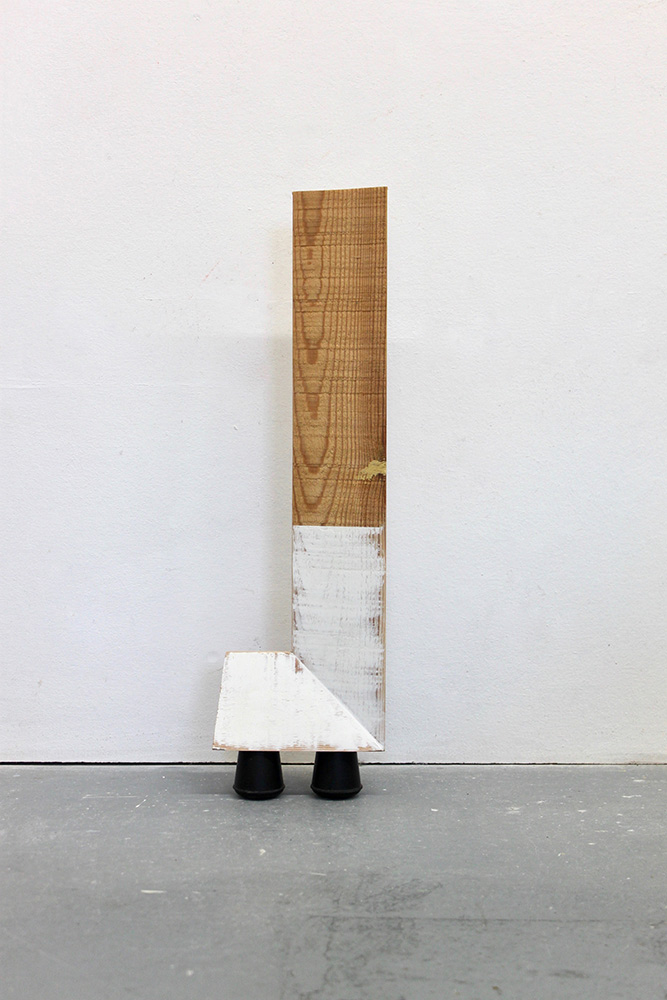

CBP: As well as the sleight of hand of misdirection in some of these works, there’s a quirky playfulness, particularly in apparently figurative pieces with castors close together as feet on ‘Corner.’ Is humour part of the work, playfulness to negate the work being too austere?

MT: I don’t see the language I use as particularly austere (restrained perhaps), but it can be necessary to poke at certain idioms even while you make use of them. So, yes, humour can be part of this, though I might stumble upon it unintentionally. The pieces with the wheels or “feet” resulted from feeling uninterested in the relationship some of them originally had with the wall. I could see that I was going through the motions and things were proceeding in far too predictable and well-behaved a manner. As soon as they descended from the wall they seemed to require a certain autonomy as fully three dimensional objects – and so I thought of offering them an extension to their agency by providing mobility (sometimes a compromised mobility). What had started as conventional painting panels now suggested something that might be played with, a piece of unidentifiable furniture – or, not to be too fanciful about it, something capable of its own propulsion.

CBP: The titles are often very matter of fact and functional, with again sometimes a playfully poetic slant, like ‘Painting with restless edges’ and ‘Jut, painting with shadow’ How do you decide your titles?

MT: I want titles to serve some useful function in relation to the object, but without striving to impose something that feels artificial. I used to use elliptical titles that felt like an extra component in the work – or something in conversation with it – but this came to seem forced and over-complicated. The matter of fact and functional titles that you refer to relate much more directly to the pieces and it feels as if acknowledging the behaviour or playfulness of the object takes you closer to what it is (or does) – sometimes with analogies to the body as in ‘All Knees and Elbows’, ‘Akimbo’ and ‘Painting with restless edges’. In some ways this crept up on me. I would post images from the studio online and as it was too early to think about formal titles I gave brief character descriptions – and somehow they stuck. It seemed that this approach allowed the work its own natural poetry and possible motivations.

CBP: Can you discuss the process of painting in the work, in terms of applying paint and colour, colour in found objects (readymades) and finding colour through stripping back layers? Consider this question in terms of mark making too.

MT: A few years ago, feeling frustrated and bored with my own over-familiar habits, I decided to move from oil paint to acrylic, to abandon canvas and to pour paint instead applying it with a brush. Having constructed a panel I pour paint in layers, pausing from time to time to re-configure the piece, mending where necessary, until the piece takes on its own identity. Sometimes the raised lip of layered colour at the edges remains, but often I need to knock everything back with a sander in order to increase the transparency of the surface and bring up lower layers. I don’t have a formula for this and although things have characteristics in common I welcome the different directions things can go in. Even the accidents of cutting that occur when the saw isn’t working properly (which does happen) can be made use of. I often have two or three freshly-poured pieces drying at any one time and may also pick up and work on fragments of found material alongside them. Very occasionally I will use a brush, but the slight remove that pouring allows me is important. I might judge consistencies and set the process in motion, but to a degree I am a spectator to what happens and I like to have a loose attachment to my original intentions. Which is not to say that I don’t attend very closely. When working with found objects I intervene less. They bring physical properties of their own and my interactions with them tend to be limited to zones of refurbishment or emphasis.

Perhaps rather at a tangent, but relating to the idea of surfaces and attention, I have an image in my mind of the dark green lino we had in the house I grew up in. No doubt because there had once been some damage, a very small rectangle of lino, no bigger than 2 inches long, had been inserted as a repair. What I remember about that floor is helping my mother to polish it on hands and knees; and the intimacy of the relationship with that tiny and precarious rectangle.

CBP: What’s your current studio practice and routine? What are you working towards at the moment?

MT: My current circumstances mean that my working time is often fragmented, so I tend to work in shortish bursts. I have a studio in an outbuilding at home so although I do most of my work in the mornings I can come and go easily during the day, if only to check on states of drying. I have adapted to this and find that it works well with my thinking and making processes.

I have a couple of longish-term exhibition projects that I am involved with, but while conversations related to these continue to suggest fresh perspectives I am essentially continuing to generate my own questions and answers.

Molly Thomson was born in Scotland. She studied Fine Art (sculpture) at Edinburgh University and Edinburgh College of Art, followed by an MA (painting) at the Royal College of Art in London. She taught painting at Falmouth College of Art and the Ruskin School of Drawing and Fine Art before becoming Subject Leader for Painting at Norwich School of Art and Design. She has exhibited nationally and internationally and was a co-guest-editor (with Barbara Howey) of the “Commitment in Painting” issue of the Journal of Contemporary Painting. She currently lives and works in Norfolk.

Forthcoming and recent exhibitions include; 2021 Que des Femmes, 6th Biennial of Non-Objective Art, Pont de Claix, France. Perceiving Anomalies, Yellow Archangel, General Practice, Lincoln, England. Rock, Paper, Scissors, Houghton Hall, Norfolk, England. Orbit, Poimena Gallery, Launceston, Tasmania.

2020 Vitalistic Fantasies, Contemporary British Painting, The Cello Factory, London

Further links: