Natalie Dowse: Artist of the Month – July 2024

Artist of the Month July 2024:

Natalie Dowse, selected and interviewed by Paul Newman for CBP.

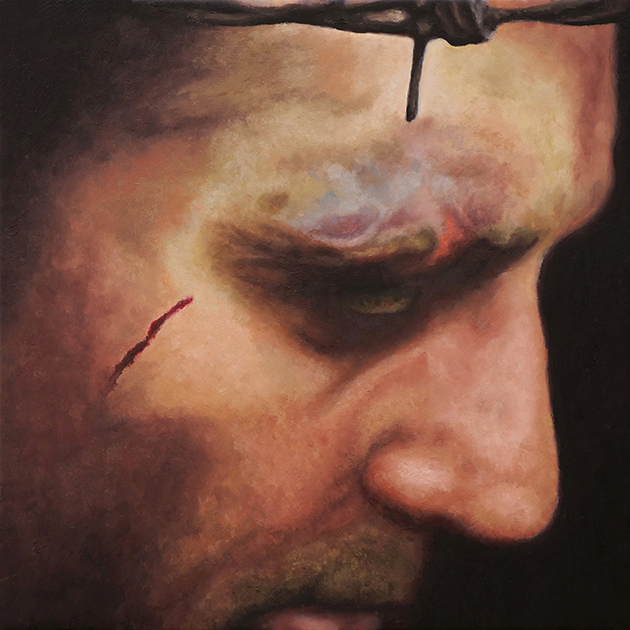

For July’s artist of the month Natalie Dowse discusses her Mise en scène series. Mise en scène brings together a number of series based on cinematic tropes: a cut to the cheek framed within the eye of the lens; actors crying for the camera; a woman with a cut lip as a result of (usually) male violence; and others in progress.

First created in 2015-16, Natalie returned to these series last summer, 2023, to take the concept further….

CBP: You’ve returned after 8 years to the Mise en scène series of cropped close ups of faces based on film stills. They depict recontextualised characters crying or with small cuts. Can you re-introduce this series and what made you return to it again?

ND: Yes, as you say, I began working on Cuts and Crocodile tears in 2015-16. The title Mise en scène (i.e. production, direction or stagecraft) came about because I wanted something that would neatly connect these and other ideas I had in mind related to film. I usually work in series, and I had always felt that these were ongoing. There’s something about the concept that interests me deeply so I always knew I hadn’t finished with this one, but it was a case of restarting when the time felt right.

The last time you interviewed me for AOM was February 2021 where I had touched on these series, and others such as the gymnasts and Between Dog and Wolf, and we ended talking about three paintings I had been commissioned to make for an exhibition about the late actress Fenella Fielding. It was whilst I was working on these – painting close-ups of a face and working from film captures – that I began thinking about the Cuts and Crocodiles tears once again, and I started collecting new source material.

CBP: In sourcing your stills, do you have a memory of a scene from a film and go searching for it? Perhaps finding the scene wasn’t as you remembered it. Roland Barthes talks about searching for the ‘right’ photograph of his mother in the attic at the beginning of Camera Lucida. Maybe your process is more matter of fact in making note of suitable imagery in your general viewing.

ND: Generally, I make a note of potentially interesting scenes as I am watching something. I record a lot of films with this in mind, so that I can return as often as I need to. Catch-up is a great help too. I found that noticing material is a bit like when you get a new car – once you own it you notice all the others that are the same colour and model as yours. You become more aware and attuned to noticing. Spotting tears and cuts has become not too dissimilar to this. Nevertheless it is a lengthy process to find and collate material – isolating just a single frame out of hours and hours and hours of watching.

The ‘right’ image can be elusive in many ways. I will shuffle back and forth, frame by frame, until I find what I want. It’s not always there though, sometimes I wonder if what’s going on in the film, or maybe even the soundtrack alone, can change perception. When that one frame is isolated it’s not the same at all.

On occasion I will remember a film from the past and seek it out. On other occasions, someone will mention a scene in a film. Often, you are quite right, sometimes a scene can be ‘mis-remembered’, and in some cases, even after carefully selecting and I’m well on the way on something, it turns out to be disappointing and I end up scrapping a lot of work.

CBP: Can you discuss select examples from your new Crocodile tears and Cuts series?

ND: I wouldn’t want to necessarily talk about any particular painting, but instead, would like to like to discuss each series in slightly more depth.

Firstly, another reason for returning to them is that I felt I had unfinished business. What I mean by this, is that I had some frustrations with some of the earlier paintings that I wanted to address.

I have always been inspired by the concept. However, I wanted to hone this to make this the most prevalent reading. A big part of the newer work is that the protagonists remain (mostly or almost) anonymous. In the earlier Cut paintings the source material wasn’t cropped as tightly. I think I was going for a slightly different aesthetic. However, in many cases, this made the actors recognisable, or led to the audience playing a guessing game as to what role they thought they were playing. I felt this pushed what I felt was the most important idea behind the work to the back. I realised this reading of the paintings is perhaps inevitable, so for the new work I wanted the paintings to reflect more of the concept.

The Cut series focusses on something of a cinematic cliché. A cut to the cheek is a kind of visual shorthand to show that the actor has been involved in a fight or some other kind of danger. In older films particularly the cut is often quite neat, and always strategically and artistically placed to look ‘good’ in camera. The paintings parody this. The cause might be an accident, or perhaps from a violent or a heroic act, but the women I choose are usually strong characters – that’s important to me. Another important thing is that the violence isn’t real, the cut isn’t real. It’s only make-up, a painted mark in itself.

With the early Crocodile tears paintings I was able to address my initial frustration somewhat by cropping the images further and rendering them in black and white. This made the actors less obviously recognisable, but I missed using colour which I find so enjoyable and challenging!

An unexpected outcome, and one that I have embraced, is that my new approach for the Crocodile tears paintings in particular has made them so much more intense and emotionally charged. Even out of context they seem to have an intensity, but I think without being sentimental. Perhaps it’s natural human empathy that leads us to relate, without necessarily knowing why.

Another important thing about the new works is their size and the intrinsic scale. Most of these are smaller than the older paintings – the new paintings I have completed so far range from 15cm square to 40cm square, and I have other formats and larger sizes on the way. What I mean by intrinsic scale is that the subjects in many of the paintings are huge in relation to the relatively diminutive size of the support, and weirdly, the finished paintings seem so much larger than the unpainted panels. There’s something about this, and the rhythm of the variety of sizes, that I love.

CBP: You talk about your paintings abstracting from the original context of the film and becoming their own narratives for the viewer, can you discuss this in more detail?

ND: Yes, more often than not my final image represents a tiny part of the frame; they are cropped so tightly that most of the scene has been discarded. I completely erase the original context – it’s not necessary for the viewer to see or to know the original story, I want to kind of create my own story, but leave room for the viewer to make their own reading. I work towards an extreme close-up, very carefully selected, edited and cropped, to draw out precisely what I saw in that particular moment. Some of the earlier paintings have a hint of, say, religious subjects. I really enjoy this nod to the Baroque and other precedents, and in the new Cut and Crocodile tears paintings I have homed in on this much more.

I’ve decided that I’m not going to reveal what the sources are. Although there is still a chance of recognition I don’t think this is the most immediate reading. If it turns out that the actors or characters are known by the audience then that’s OK too, as I’m now happy that this element has been diffused enough.

CBP: The Cut lip series is an extension of the exquisite frisson of the cuts series. Can you talk about the element of the eroticised and fetishised in the Mise en scène series in relation to these notions in cinema and in the gaze?

ND: This is a brand new series which represents a very particular filmic trope: unlike the previous two series where the actor can be any gender, a woman portrayed with a cut lip is almost always suffering the aftermath of violence inflicted by a man.

The Cut paintings parody a cinematic cliché; the Crocodile tears paintings convey emotion; but the Cut lip paintings address an altogether different and quite specific signifier.

I must admit I had some reticence about making and showing these paintings. I’d noticed, through my own viewing experience, that unlike the perfectly placed cut on the cheek, which more often than not portrays an act of heroism or accident, a woman with a cut to the lip stands out – they are inherently more intimate and distressing in their circumstance. I am very aware that there is a dichotomy here: a beautiful but bloodied mouth places the viewer in an uncomfortable place, even before other allusions come into mind. When those allusions do enter the viewer’s head, that dichotomy becomes even more discomforting.

Although the subject leaves me somewhat uncomfortable, I felt that that discomfort should be shared. They make an important point, and by placing us in a dilemma they highlight that. Many of these images are taken from mainstream film and television, broadcast into our homes. If we don’t like it we can turn it off or change channel. But just as film and television often draws on real life, it is by definition a reflection on society. Therefore, I didn’t want to avert my gaze and not make these paintings.

CBP: The new paintings look and feel richer, more saturated in their colour than the previous series, almost with a sense of nostalgia. There is a feel of 20th century technicolor film and cinematic lighting in this regard. Is there a connection with the patina of the film source, or is this more naturally an evolution of the painting process?

ND: I’m really pleased you picked up on that. To be honest there’s a bit of both going on. Firstly, yes there is the specific lighting conditions of the film, and that will play a part in my choice of subject. Beyond that the process I use to capture the image goes through several stages which, through their nature, result in low resolution images. These come complete with glitches and jpeg noise, which I have to try and ‘see through’ when painting from them. Next, cropping and enlarging adds more noise to the mix. I also make adjustments in Photoshop, to lighting mainly, and sometimes to shift the hue.

Because the images have come from screen-based media there is this slight nod to the back-lit light and colour that emanates from that, which is something I like to exploit. I relish working from degraded images as it offers me a sense of freedom.

As well as this there’s the painting process itself, where I may tweak, refine or exaggerate the colour to make the painting work as it develops. I like the idea of the paintings appearing nostalgic too, I suppose it has parallels to the actor captured and trapped in celluloid forever.

CBP: What are your plans for this new series?

ND: I can see myself working on these for a long time yet. I have more in progress in the studio and an exciting and inspiring bank of source material waiting for me. There are also some new series to come under the Mise en scène banner.

I have only just published the work I produced during this last year on my website, and I’m now starting to post them out on social media. I decided to hold them back for a while so that the concept would be stronger and more evident. I made a rule for myself that I would only post them once I had finished 30 paintings. I don’t usually make too many rules for myself, but having this particular goal has helped to keep up the momentum. As artists there can be a pressure to be posting on social media all the time, showing that you are active in this high-speed driven world. It turned out to be a useful discipline and it felt good not to subject myself to this – after all my paintings take a while to make, so a constant stream of new content isn’t easy for me.

I always envisaged these being shown together, so ideally that’s how I would love to exhibit them – to be able to see the entire body of work as a whole. It would be exciting to see what rhythms they create and what conversations they would spark between themselves: the rhythm of scale, the focus, the suggested and new narratives. I’m looking for that perfect space!

Natalie Dowse has exhibited her work nationally and internationally. Her work is in public and private collections, including the Jonathan Vickers Collection, the Robert Priseman Collection at Falmouth Art Gallery and the Priseman-Seabrook Collection. Her work is also featured on the Art UK website of the UK National Collection.

She was the recipient of the Jonathan Vickers Fine Art Award, a year-long residential project which culminated in her solo show Skimming the Surface at Derby Museum and Art Gallery. Natalie was awarded an international residency to Riga, Latvia, by the Arts Council England International Fellowship programme in partnership with Braziers International Artists’ Workshops.

https://nataliedowse.co.uk

Instagram: @natalie.dowse

Recent exhibitions include: 2024; Assembly, The Old Gym, Rye Creative Centre, 2023; Arcadia for All? Rethinking Landscape Painting Now, Attenborough Arts Centre, University of Leicester & The Stanley & Audrey Burton Gallery, University of Leeds, X – Contemporary British Painting, Newcastle Contemporary Art. 2022; Fenella Fielding: Actress, Paint Edgy: Contemporary British Painting and Guests, Artspace Gallery, The Ropewalk, Barton on Humber, Sound and Vision – where Music Meets Art, The Merton Arts Space, Wimbledon Library, Conversations with Nature, Alison Critchlow, Helen Thomas & Natalie Dowse, Wakefield Art House, Wakefield, Wish you were here, Terrace Gallery, Leyton, London.