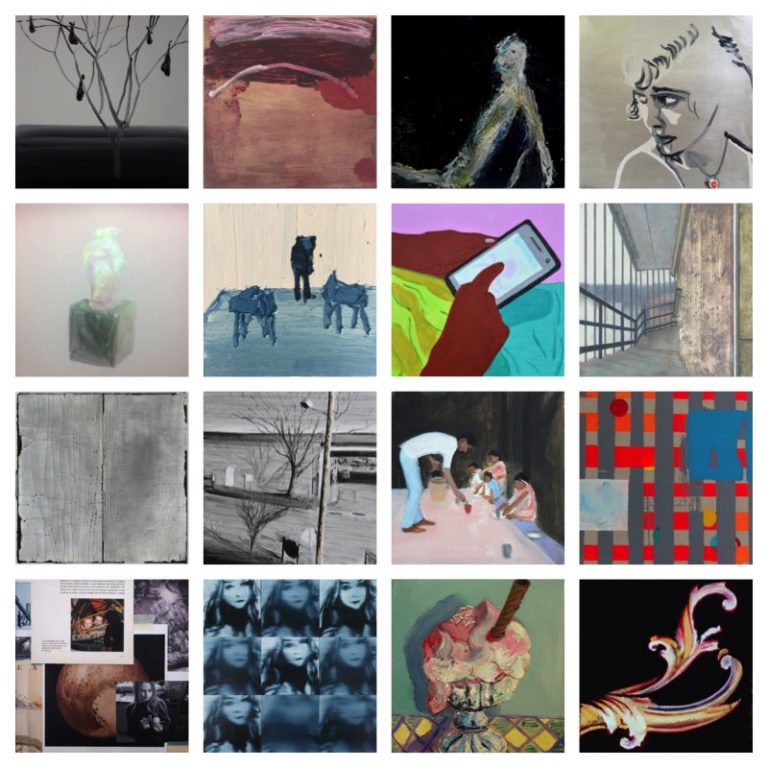

Painting as Terrain Panel Discussion

Painting as Terrain: Transcription for Panel Discussion and Walk Around with Chair Emma Cameron (EC) and the Artists – Jane Frederick (JF) Jyoti Bharwani (JB) Daphne Leighton (DL) Claudia Boese (CB) Ruth Philo (RP) Mary Romer Greenfield (MR) Alison Downer (AD) Absent.

Emma Cameron: In the accompanying essay by Dr. Matthew Bowman titled ‘Ground Graspings- Heideggerian Reflections on Painting as Terrain’, he considers the term Grunde or Ground. Painters often use the term ground to refer to the surface they paint on and also many painting materials are made up of ground up rocks and minerals that are taken from the ground. So, as we go around, we’ll be asking the artists to tell us something about what that word ground and maybe what ground graspings means to them.

Jane Frederick: I’m hoping that you’ve all had a bit of time to get a sense of these paintings.

It’s useful for you to know that when I was a young child, one of the things that my parents did regularly was to take me to stately homes and gardens. Chatsworth House in Derbyshire was the first one, and is still one of my favourite places in the whole world. Since then, I’ve had this passion, it seems to have just grown stronger as I’ve grown older, and I’m beginning to understand why-because going into a formal garden as a child sowed a seed; I was able to be who I felt I wanted to be. I would draw and run and play with my brother and I realise as an adult that when I go back and look at these formal places, it doesn’t matter where they are, they could be anywhere around the world, it gives me permission to be that person again. And I think that’s probably what draws me back. For me it is a grounding experience to go back to these places.

What I do struggle with though is that a lot of these gardens were designed by men- many in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries to show their power and their influence on culture. Not always…I’m thinking about Renaissance gardens, and in particular in the Western world. That’s an interesting side issue I’ve been thinking about.

This particular garden, (Villa Gamberaia) resonated with me. It is a very old garden in a village called Settignano on the hills just overlooking Florence in Italy and is a very beautiful, intimate garden. It is often used as a reference point for those interested in designing gardens. It has a lot of key elements that you might find very useful to learn from, I knew I wanted to go and experience it for myself.

It evolved over centuries, and in the late 1800’s, a Romanian princess called Jeanne Ghyka apparently took over this villa and decided that she wanted to put the feminine into the space. She re-designed several areas including this water garden here (pointing to painting), which was originally home to flowers in each of the quads of the parterre. She flooded them because she wanted to reflect the sky in the water, so in terms of the ground and the sky if you like (the celestial world that we’ve all been thinking about in this exhibition) this garden actually mirrors both of those things.

There are several different parts to the garden, which you are invited to experience from different viewpoints. The thing that excited me when I made these paintings (and there’s lots of them in my drawings as well) was how a Renaissance garden is designed to pull a guest through a space and take you on a journey as you move through it. I love the playful side of it, so I wanted to make paintings that somehow echoed how it feels to look at a formal garden, but perhaps dare to say something about how it feels to move through those spaces. I have played with lots of different ideas over the years, and my recent foray has been using convex lenses. When I visit the gardens wherever they are in the world, I will photograph and draw them many, many times, then I create collages in my studio, which I then photograph through a lens. That homogenises all of the images and makes a new garden form which is from my imagination- that’s how they become portals.

Audience: Are they oil?

JF: These are acrylic paintings. It’s worth saying that when I’m painting, I’m thinking of the grund as pigment, I choose to work on board because it can take some abuse, I can really hammer at it, and I create a wet space at the beginning. I flood it with lots of paint and I’m pushing and pulling and dragging it until I get what I want.

Mary Romer Greenfield: Is that the first preliminary step of pouring the paint on and then dragging it?

Audience: What do you drag it with?

JF: All sorts of things, brushes, bits of cardboard, squeegees. I just want to see what the paint will do, but kind of flirt with abstraction and the concrete, I haven’t got there yet…but I want to hover between the abstract and the representational.

MR: It’s quite interesting how you’ve done the sky and the foreground here they are very abstract, and then you’ve used very well defined drawn spaces of the garden, so it’s like structure and non-structure.

JF: Absolutely

EC: We could stay here all the day, but we must move on, any quick questions?

Audience: Can you say why you were so restrictive in your palette and why those particular colours?

JF: It’s a really good question and I ask myself this too. I spend a lot of time looking at the computer. I scan my images in and I will literally just play like a child with the colour balance and I sit and I stare at it as I’m moving the sliders and I wait for that gut thing, and these are the colours where my gut said, ‘that’s it’. That’s all I can say.

EC: Wonderful, thank you Jane. (Clap)

We’re going to move on to Jyoti and then get back to Daphne. Find yourself a space. So Jyoti, you’re the curator of this show, can you tell us something about the ground and terrain that interests you?

Jyoti Bharwani: This series of paintings, of which I have 2 paintings in this exhibition, are based on Black Stone Space and I was looking at the Black Stone which is the cornerstone of the Kaaba, and also in the Christian religion as well as Islam – there are theories of how the Black Stone came down to Earth from the heavens, and when it came from the heavens it hit the ground on the earth where they placed the first temple. There are also scientific theories of where the Black Stone came from, and theories which we have not been able to define or determine what this Black Stone’s constitution is.

So, I was interested in how humans flock to places where there is this Black Rock, and that it has a power and a healing. People rub their hands on it and feel atoned of their sins and I was interested in representing that indeterminate nature within my painting.

To me, the ground came in by using the materials to reflect the invisible subtle layers that we don’t see, but we feel, that need to be drawn to something- not that we all feel this, but some people feel, and even the scientific theories, they just want to know what it’s made of, and they’re always looking for what it’s made of; it’s a quest. I was interested in finding why that is, and in James Elkin’s book ‘What Painting is’ he talks about paint being made of pigment and binder and that pigment gives the crushed rock colour, and the binder is the fluid or the water. So it’s rock and stone, and the idea of using oil paint to paint this subject was just the perfect combination. And what I did with the paint, was basically, I tried to re-enact the feelings that people will be getting when they arrive at this stone, whether they are rubbing it or whether they are feeling that they are drawing out their sins, my process is to get the techniques that show that which I find exciting; and I try to play with the balance of the pigment and the binder, so we get different types of medium, and play with medium and the pigment and break them down to the raw materials, and try to use them in different concoctions, quite alchemically, to show what would come out.

I really didn’t know what would happen, it was almost like a journey, the representation is quite astral, and this was quite nice in the circle of the process, that it almost felt that it was cosmological as well as being related to the ground and earth. And that’s what I can say for now.

EC: Your passion really comes through on this subject, any questions?

Audience: Can I ask how you made your marks? It looks very dappled and lovely. Is it lots of layers?

JB: That’s a lovely question, because you’ve prompted me to say something else that I wanted to say! I did use a lot of fine sprays, and that is with a lot of experimentation with oil and pigment, because when you do mix oil and pigment to become a liquid, which you want to spray, it’s not actually easy to spray an oil liquid. It’s easy to spray water, but as you start introducing the binders that come with the oil paint, it’s very difficult to spray, and also the control is not there, so it’s about using another implement to apply the paint on so you don’t get the defined shapes, it’s almost flowing into each level, and the levels that I’m representing all flow into each other as it were, so I felt that was perfect for the subject.

Audience: Is it like a machine that you use to spray?

JB: I use different types of sprayers, and some are better than others. Perhaps you could visit my studio to see.

EC: Any other questions?

Audience: What put you onto the Black Stone in the first place?

JB: I’m a research based artist, so it’s from conversations with people who have been telling me about the Black Stone originally, and I got interested, and once you feel that spark of hearing about someone going to a place where they felt they were getting some form of healing, and at the same time, someone was telling me about the Black Rock, which is a Hindu place where people flock for pilgrimages. It was that tide and that pull towards a part of the ground and the earth where I dived in, and I started looking into it more through books and what not. Interestingly, there is not actually that much information available about the Black Stone, it’s quite mystical in a sense; and I found that the more I looked, the more I wanted to know and the more I didn’t find, and it was almost a quest -what is it about?

Audience: Recently, this last week, Bettany Hughes did a wonderful programme on Aphrodite, and apparently the original Aphrodite was a black rock. There were also stories of people going up to rub it and it’s a strange compelling, almost figurative but meteorological looking rock. So the idea of Aphrodite, she expanded it from that primal condition through Greek sculpture, through it’s servicing of female emancipation, and the appropriation of female emancipation through it. Black rock as we started with, on a very rich discourse became a story about freedom and emancipation of the woman.

JB: Thank you for sharing that

EC: Thank you Jyoti (clap)

Audience: One more very quick question. In the catalogue, it has the painting hanging the other way around, is there any reason for that?

JB: It was in the making of the catalogue that some of the pictures turned around, and we were not able to turn that one back; and with this painting, it doesn’t matter too much which way you hang it, it can be either way according to preference.

EC: We’ll now track back to Daphne’s work now. So, Daphne – ground, terrains, we can almost feel it when we look at your work. Tell us something about that.

Daphne Leighton: Ground and terrain have been my concerns since before I started painting. Even the title of this exhibition actually dates from when I was doing an MA in English Literature and very involved in poetry and words. Eventually I became absolutely fed up with words. Gradually from photography and video I moved to oil paint or acrylic. Suddenly I wanted something different, perhaps due to the changes in my personal life, but I see that my progress all along has been to something more tangible, less verbal. What I was exploring in this series of paintings was how two very different things can go together. Or how two people can go together – the personal issue at the time. How can a bit of canvas go together with plaster and jute? Or plaster and a piece of rusty old iron which is one of my passions? Can they blend? Can they work together with oil paint? After all this is painting as terrain. Are they paintings? What happens when you want a surface with a lot of crevasses? How can you make those crevasses?

Well, you could use a vast quantity of oil paint like Auerbach uses, but I chose here to make them with plaster and some cement underneath and then a plastic bag which just got pulled into different shapes as it adhered to the canvas. This was a bit of a slow process, especially with my favourite bits of metal. And I felt what it gave me was something that to me is very alive and very tangible. I probably found the plastic bag in the street, exactly in the form you can see in the painting (points to canvas above plastic crevasse canvas) which is much more defined? Can they work together with the surface that I’ve put it on? That still remains a question. You’ll see as things progress, because those two over there by the piano are mine as well. I started using different materials, even bird bones from the beach. Obviously for this exhibition they had to be small paintings because they had to come from Jerusalem. In fact, I’ve got one that’s about sort of that high and that wide (indicates larger expanse with arms wide) using the fruits of a trip to a wonderful beach and where I found half circles of rusty metal which I could take back to my studio to work with. Last week in Cordoba I saw a wonderful sheet of rusty metal but unfortunately I couldn’t take it home.

EC: And isn’t it lovely, that passion for rusty metal, well that’s what being an artist is, your passion and endless curiosity. What would happen if..?

Audience: Can I just ask, in that one over there, are they beads? They look like beads.

DL: No. That’s just jute, a bit of green sacking.

Audience: Honestly it looks like beading to me, so it’s incredible how you did that!

DL: It’s just a strip of it.

EC: Thank you Daphne (clapping). Ok. we’ll take ourselves past Daphne’s beautiful paintings there; we’ll walk round ‘til we get to Claudia’s.

So, Claudia, the terrain, the ground, the process?

Claudia Boese: Ok, well, I’ll talk about two things, first about Matthew’s essay. Jyoti wrote that in the beginning, painting was our search for the imagination, our search for the primary creativity. I must say, I don’t think so (laughter). I feel it quite strongly. I feel we are already painting things we know about; we are not searching for our creativity, our primary creativity. We already know about it. I feel very strongly about this. Of course everybody takes it somewhere else. Quoting Winnicott, that place of finding the self that we have already found ourselves.

Audience: Well we’re a bit old to have not found ourselves.

Audience: Well we haven’t all found ourselves!

CB: On one level of course we move on. I’m interested in psychoanalysis thinking about being. I call my work an activity of hanging on in here. I asked my mum why did you bring me into this world Mum? I didn’t ask for it. I’m really interested in this sort of thing, and also one other thing, it does relate to Jane’s work a lot. I am interested in that space where we come out of, and it’s quite natural, suddenly we just pop out, and we are in this world. I see it as what we bring to the world; I see Jane’s work as that place. It’s moving and we’re moving from one place, which is very protective and nice, but then we move out into this world.

So here, this work is about similar things. The ground itself is the most important thing for me, because it’s the planet, it’s where we are, that’s how it is. I always come back to the ground, in whatever I use. I’m quite transparent about what I do here. I leave it all open for you to see what I do. And I…(looks to painting) it’s called ‘Capitalism, what have I called it, it’s called?

MR: It’s called Culturalism

CB: It’s called Culturalism, but I could call it Capitalism as well as Culturalism. It is also about quite the opposite of Culturalism. I’m a romantic, hence it is on the romantic side of things. Painting about nature, it’s a green here (pointing to painting), and it’s earthy here, so I am a bit of a romantic, a romantic woman, talking about, this is the planet we live on. When I paint, I draw my ground and think of 6 million years. I paint in relation to this and this is the hanging on activity, a reminder of my existence. I just do this to remind myself I’m here, and it’s another language to talk about this reality like in books. There is a reality for painting. It is just another text about our reality. Like writing about psychoanalysis, or something similar. But at the moment, that’s what this work is about. It’s quite hard to put into words what we paint.

Audience: That’s because you painted it.

MR: I was interested in how you interpret the word Culturalism? You said something about five minutes ago about Capitalism, are they closely associated in your mind?

CB: We live in Europe. We could have had such a nice life if we had just a bit of nice Capitalism, just a bit.

MR: So that’s behind the title?

Audience: I’d just like to ask about all the lovely green paint in it?

CB: I started thinking about paint itself a long time ago. Currently I’m thinking about paint you can buy in shops, £2 only, they are better than what Gainsborough had a hundred years ago? I think it really matters what you paint. I used to be painting with oil on canvas only, but I’m mixing it now, and I don’t care what happens, because time will work on it. This is acrylic paint that green? And with oil paint, I like the way they communicate with each other. On another level, I don’t care if it doesn’t last 200 years. I was brought up with ‘oh you have to use this you know’, and now I’m not into this at all.

Audience: Is that because it separates?

CB: Yes, and it does it, and I’m taking the risk of messing it up, but I feel it’s a good risk.

EC: Taking the risk of messing it up. Thank you, Claudia (clapping) Now we’ll head over to Ruth. This one here, and that yellowish one there is by Ruth. This one here and that yellowish one there are both by Ruth.

Ruth Philo: I’m Ruth and I work in south Suffolk, and a lot of my painting comes about by walking. It’s about my connection to the world and the paths that I tread. When I begin a painting, there’s a lot of inner and outer, so I might have an idea from my brain that when I actually pick up a paintbrush all that seems to evaporate. So, I think I started with these paintings just thinking about dividing the ground in some way, and then keeping them really simple, but as always happens, they go off in different directions, so they became more divided. I’m very interested in materials and the geography of pigment, so wherever I go I’m always looking for pigment reflecting that place. So, when I went to Naples, my aim to get some Naples yellow, well that wasn’t too difficult. I kind of collect them up and make my own paint, and I’m just interested in the real subtleties of colour, and I think probably here I was just deciding to work with one colour, that I’ve been painting for a while now with graphite grounds, often I have gesso underneath, these are gesso on canvas and then I’ll put graphite, which is graphite powder, and then working into it with maybe an acrylic medium, and that gives a very solid dark base to work from. And on top of that there are layers, thin layers of oil paint, often mixed with wax, so there’s often lots of wax, but because I’ve got that dark ground, I can really reveal it. So, I’m interested between the interaction between the surfaces that you see and the layers underneath. I do feel painting is about inner and outer worlds. So I can tell you when I walked around here and looked at these spaces, interior spaces like rooms, but also exterior spaces and lives, and my first job was working for an archaeology commune, and I didn’t think that ever affected my personal practise, and now I have to agree that it does, because that idea of grounds, and revealing. A lot of these are painted up, and then I wash them down with white spirit, to see what happens underneath, to you can get different interactions, and the paint moving across boundaries. The titles come at the end, but usually they’re about something that’s been going on, and I have been in a lot of waiting rooms, and I kind of, and you know that way that you trace the walls, trace them all the way along the edges, and if you’re in a waiting room, and you’re waiting for something to happen, but while you’re waiting, you’ve got nothing much occupying you. Having said that they’re not a particular place, they’re as much a place in my mind as they are some places outside.

EC: Questions? Does anyone have any questions?

CB: I’m interested in the square and rectangular space. Can you talk about your decision to use a square or rectangular space?

RP: I am interested in the shape of paintings, and for a long time I just used a rectangle, a very small shape, I painted them all the same size, and more horizontal, and then suddenly I just changed so I had them all vertical, and then I thought, I used to paint much larger, and then very small, and then I just thought I’ll go for a little bigger than the little ones. And I think I was experimenting with dividing, and I had this idea of what happens when you divide a rectangle or a square, squares are harder, and some of the paintings in this series are not divided much like this, so you’ve only got one line across the middle, so I felt in the end with the painting I was going around and around in circles. I had them in my studio and someone came and looked at them and he said ‘why have you still got these up on the wall? They’re not finished, are they? You’re not working on them, are you? So, I stopped.

EC: Anyone else?

JB: I wanted how you got the wax to mix with the oil paint? The surfaces are so beautifully silky smooth, when we put them up they appeared so smooth and I wonder if people are allowed to touch them?

RP: I work with squeegees quite a lot; I mix the pigment with some oil binder and wax at the same time, so you have wax. It’s not beeswaxes, I use different kinds of wax mediums, most are artist materials; manufacturers make a wax, and I experiment with different thicknesses. Some sits on the surface, some blends with the paint, it depends on the viscosity, but there’s a completely thick wax that I like, you know, the pigments are completely suspended within it. They’re very thin layers of paint, although they look as though they’re very solid, they’re not.

EC: Thank you Ruth. Now we have Mary’s work. Which one shall we gather round Mary? Try and arrange yourselves where you can see and hear.

MR: You may be wondering why these are clouds and not terrain. So, my thinking is that the terrain in which I work is really in my mind, it’s not the ground. I paint clouds as a metaphor for memory.

The idea of memory came from a bunch of letters that I received from my brother thirty years ago. He lived in Africa when he was only twenty-one and I re-read them thirty years on and these memories came flooding back, almost billowing like clouds. So I started to paint using clouds as a metaphor for describing the sensations and emotional states that these letters brought back to me.

They are especially poignant, because my brother sadly died at the age of forty-seven. He was a diabetic, and he collapsed and didn’t recover. So the letters then became even more precious, although I struggled with actually painting letter forms, and my paintings got very grid-like, and I wanted to break out of that, so I started a series of paintings using a rather monochromatic palette of greys and blues and white and I put the paint on in very thin layers, so that they dematerialise as you’re watching them, as does memory.

This is what I was conjuring up and in that series there were also lines almost like grids. A bit like Jane and a bit like Ruth, there is this dual purpose going on of something abstracted and yet with a construction put on it. Then I thought right, I am not doing that anymore, and I went back to working with colour, which I have always loved and I just sort of let the colour explode onto the canvas.

When you are mixing different colours, you get different tones, some are light, some are heavy, they sort of describe the different emotional states I experience, where sometimes I’m very serene and calm, and other times I have got a lot of anxiety swirling around. I really like working with this, because it kind of describes the polarity of emotional states that I experience, as I am sure all of us do…there are times in our lives when we’re calm and everything is lovely and serene, and there are other moments when everything kicks in, and you’re filled with anxiety. Whether it’s about the planet and the destruction of the planet, whether it’s about the political situation, or situations within your family, which is obviously deep inside…So, it was trying to encompass all those things, and an intimate story as well as a big story, which I think affects all of us in different ways.

EC: Wow, thank you Mary

DL: I’d like to make a comment, Mary and I have known each other for a few years, and we painted together at the Slade, and I remember one of your memory series as a big hanging piece of paper I think, that hung right down and was totally plain. And it seems to me as if you’ve allowed the painting itself to be a terrain in which you find far richer responses to the letters that you received or memories in general. Am I right?

MR: Absolutely right. Yes, you’re probably describing it better than me, how I think and work.

Audience: Am I right in saying, from what you said, that the reddish part is representing thought, memories and emotions and feelings, and that red is invading the space? I think that invasion of the space depicts that nicely. Invading the space, which is calm.

MR: And you know emotions sometimes do invade the space, I really like exploring those two dualities of serenity and tumult in my work. I also love Renaissance painters, I think however much contemporary art we look at and admire, they are the artists that come back to me again and again.

EC: Thank you (clapping) Let’s just stand here and honour Alison Downer’s work. Do any of the artists here have anything they’d like to say about Alison’s work?

MR: I could say a little bit, as I have spoken to Alison quite a lot about her work and her artistic process. Much of her work is concerned with the environment and how this is changing with the destruction of our planet, which we’re all talking about this a great deal. Programmes made by David Attenborough draw attention to the issues surrounding this destruction. Alison actually mixes her own pigments with mediums. She is interested in using pigments found in the earth and soil…(Mary pointing to the canvas). The use of rectangular format represents the same dimensions as that of plasma screen televisions and mobile phone devices which we are all looking at a great deal, whether out and about or in our own homes. She is saying, she is trying to talk about the effect of this rectangular shape, this dimension because when we are looking at our phones, when we are looking at the television, these are the dimensions on which we view a lot of imagery, she is interested in fusing the use of technology with pigments and mica found in the earth.

JF: I think Mary has just described her work beautifully, I think what I’d like to add, from a viewers point of view, is that if you feel inclined, and you’ve got some time, spend some quiet time with this painting, because I think you need to investigate it. I think it works on you very slowly, and you start to appreciate how she’s stained and dropped the colour and how it floods and accumulates, and you get these sort of layers where the pigment has accumulated, and there’s a bit of transparent pink here where it’s broken up; the soft colours seem to get stronger the longer you spend with it. That’s what I like about Alison’s work, it’s responding to technology which is all about now, now, now, but Alison’s is definitely about let’s take some time to just be with this.

EC: Jyoti you curated this exhibition, could you tell us something about that?

JB: Yes of course. First of all, I think it’s important to say that where I’m the curator, I feel that the group was all very responsible for taking ownership of this exhibition, we all had an equal say on how we wanted this exhibition to be, and that is very important to acknowledge. I feel that where the exhibition and the theme came about was by spending time together, and really, it’s taken us, this journey, about two years from when the idea was born, twelve versions and quite a lot of time together. When we made the paintings, we did actually make the paintings for this space. Well a lot of us have really thought about this space, and what it means to us and I hope that really does reflect when you look around and see that the space has been activated.

MR: Yes, it’s about how you can animate a space.

EC: How did the arrangement come about?

JB: Daphne and I did the hanging, and we all knew that we had a certain amount of space to hang our work. I really reflected on Matthew’s essay (which you’ve perhaps read) and how he talked about moving around the paintings from the ground to the air and to the ground again, and he paints a lovely picture of the paintings in that way with his words. But, as you all know, that what you paint in your mind can change in practise. When you come to a space and start placing things, they can take on their own feel, so I tried to have that feel of the essay, even though it was in a different order, and have conversations happening between works, and almost feel that we are going around the grounds of the works as you walk around them.

EC: And would any of the other artists like to add to that?

DL: I think that in the end it was the paintings that decided where they wanted to be, they found their own spaces.

JB: Yes, it’s true. We talked about that after the hanging. About how we felt that certain artists and personalities even, came together in the way that they were placed together.

MR: I really like the first title that we used for our essay that we submitted to CBP, and Daphne you started off by saying Space for Being, Painting as Terrain. That resonated with me hugely, because I think as painters when we’re working away when we are in our studios, it’s a very solitary occupation, and I think for most of us, it is where we feel that sense of being, just being, and expressing our thoughts and feelings. And that can happen whether you’re a writer, or a musician, painter or even a dancer. You just like being in that space, you feel whole, and I thought that was one of the best titles, which has somehow got dropped off the catalogue. You picked up the space for being from reading Heidegger, I believe (directed at Daphne)?

DL: No, the space for being came from my MA thesis on Samuel Beckett. And I think Beckett would have been quite happy to float round these paintings. And it was space for being, text as terrain. What I was emphasising is the way Beckett’s in particular short prose text, using words as almost material objects, so the sounds of the words and the rhythms of the words just as we are using paint as material.

EC: It’s so inspiring. We’ve got a few more minutes of questions.

Audience: I’m just thinking about everything you’re saying, and the question I thought that was really important here, is I know you’ve been emphasising this feeling of being, but when I look at the works here, it seems to me that they are also interspersed with a lot of becoming, I think they wouldn’t be aligned if they weren’t just about being, or settled ground; it seems that every one of them is living somewhere between being as you say, very quiet and emotionally aesthetic in its own way but also becoming. Particularly I was thinking the garden ones (pointing to Jane’s), there’s this huge effort to dislocate our ordinary vision, and those lovely works over there (pointing to Daphne’s) of the mental and the relationship between the figure and the ground, it’s a becoming question. What’s going to become? I thought this was really wonderful in its complexity (pointing to Claudia), I mean you also said that ‘I know who I am’, and I don’t know who I am! But the works are asking such really profound social questions about what it is to be in the world? And what is becoming of our world? And also, that there’s this wonderful juxtaposition between extraordinary beauty and this desiccated space, and I think that those contradictions invite those tensions between becoming and being.

EC: Thank you. Any other questions?

Audience: May I say something? I think that ‘being-ness’ and ‘one-ness’ is not dualistic, so if we take it as one wholeness, and the embracing of everything-ness, so that work (Mary) or this work (Jane) or that work (Jyoti) is depicting the one-ness without any judgement, within such vast and boundless being-ness, the author or the painter is not too concerned about this *

JF: I’m just picking up on what you both said-very thought provoking and useful thank you. I don’t know if anyone in this room is aware of a book called the ‘Poetics of Space’ by Gaston Bachelard? (audience responds) Some of you know it. It’s a wonderful book to dip into and there’s a chapter at the end called ‘The Phenomenology of Roundness’ that sits quite nicely with what you’re talking about- that being is round. He doesn’t define it for you, he just places the seed in your head and you just have to let it float around with you and just let it sit there and then think about it. What does it mean, that being is round? You just made me think about that; that the outside and inside of us is round.

EC: Any last questions or comments?

Audience: I think Jane, what I find quite challenging and inspiring, that use of focus and perspective which you do in a lot of your stuff, that is such a smart move, and how you turn it into like a hoover, and hoover up bits. That’s just a wonderful thing to do with painted surface.

JF: Thank you, I enjoy it.

MR: I also like the way, that in the pink one, that the figure of the woman, the statue, it’s like she’s coming at you, and yet she’s looking back, and I find that dynamic really interesting. Beautifully painted.

EC: Well I know you’ll all agree, that this has been inspiring, there’s just so much richness in everything that the artists have been talking about, and what we’ve actually seen, and I know I’m going to be going back to my studio and feeling re-invigorated thinking about painting and painting as terrain.