Sam Douglas: Artist of the Month

Artist of the Month December 2021:

Sam Douglas, selected and interviewed by Paul Newman for CBP.

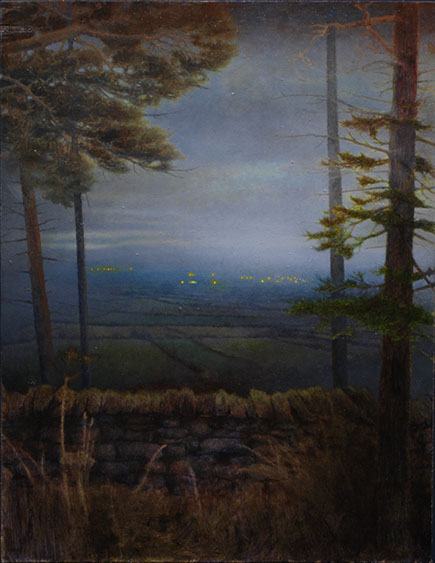

Sam Douglas works in a tradition of British visionary landscape painters of the past such as Samuel Palmer, Graham Sutherland, and Paul Nash. Like many of his 19th and 20th century forebears, he spends a large amount of his time travelling, sketching and painting outdoors. Whilst this is where his artistic process begins, it is only the starting point for the production of paintings which are much more to do with how he ‘feels’ about the natural environment and the emotional responses it stimulates than the physical topography that initially lies before him.

CBP: I remember first encountering one of your atmospheric landscape paintings in a CBP group show at the Crypt in Marylebone. I recall its exquisite surface, wrinkled with intentional corrosion and a pastoral dreamy landscape that seemed almost submerged within the layers. I thought at the time there was a fascination with studying the surface of paintings in particular historical paintings in museums and their varnished patina. I wondered if this was a source of inspiration for your work?

Sam Douglas: I’ve certainly always been drawn to old paintings where the varnish has yellowed/clouded especially to the extent where things become obscured…In particular i’ve always wanted to see the work of Albert Pinkham Ryder, but as far as I know all of his work is in the U.S, so I probably won’t any time soon. The excessive layering of varnish in his paintings and the warped and fissured surface that has developed over time looks amazing.

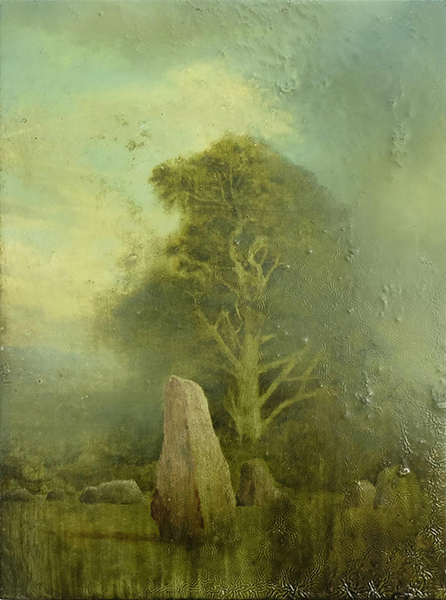

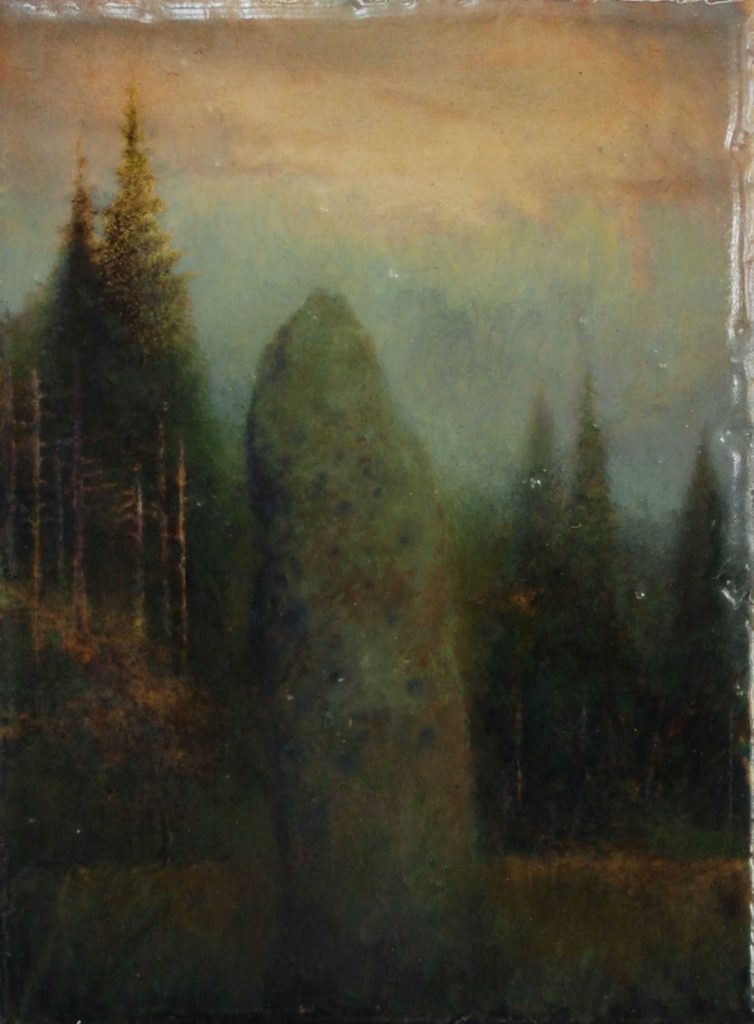

CBP: Enigmatic stone monoliths appear in several of your paintings. They symbolize time both as weathered monuments in the landscape and the time it appears you’ve invested in making these paintings. To what degree are they based on actual stone sites or conjured up from your imagination during the painting process?

SD: For many years now I’ve visited stone circles, standing stones etc, often going on cycle trips to find them and camp out nearby, so much of my reference material comes from these excursions. A lot of these places would have served as sites of pilgrimage, drawing people from far and wide, so it seems appropriate to have to invest some energy and time in travelling to them so as to shift your state of mind somewhat in doing so. However, when I get back to the studio I tend to use the photographs as a starting point and very often the image will shift, often becoming a hybrid landscape that departs from topographical accuracy.

CBP: Can you talk about the balance between source imagery; photography and drawing, imagination, and direct experience of being in the landscape in the evolution of your paintings?

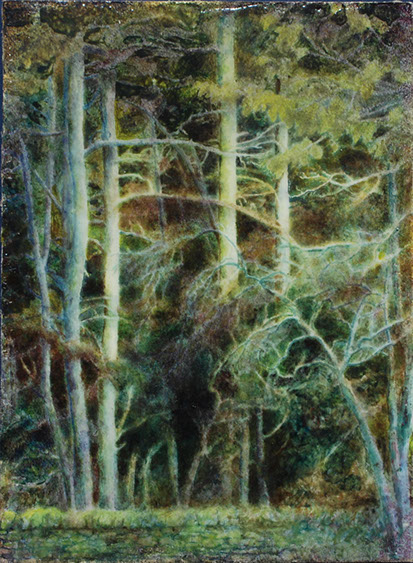

SD: It seems that there is a continual feedback loop going on through all these elements, I will visit sites and photograph them, then I often sketch in situ or later from the photographs in felt tip pens in my sketchbook to get a feel for the composition. The sketchbook work is quite loose so ideas can be set down and reworked quickly as opposed to the slow timescale of much of the studio work. I think the habitual improvisation of drawing in the sketchbook finds its way into the paintings where a lot of reworking of the initial image occurs, allowing for the development of imaginary elements in the work. I will often re-visit a site if I can and photograph and draw it again to home in closer on elements that intrigued me whilst I was painting the place in the studio and also to notice details that I may have ignored previously. This can go on for years, many paintings lie in the studio unfinished until something happens that will somehow solve the painting. These long durational paintings can be the most interesting for me as they usually comprise certain combinations of materials and ideas that I’ve forgotten about or stopped using. There is a lot of overpainting and failure in them which you can read in the surface.

CBP: The light in your work is very enigmatic, you mention the influence of romantic era painting and Samuel Palmer, perhaps Casper David Friedich too? Its like evoking the magic hour. Its enchanting but there is something a bit queasy too. Perhaps this is because it’s linked to the sometimes shriveled and corroded textures in the work, like the picture is on the turn. Could you talk about the duality of creating an enchanting picture and something that might be on to point of rotting?

SD: I was certainly inspired by The Palmer exhibition at the British museum in 2005, I particularly relate to the small scale of his work that draws the viewer in close so that you start to notice the surface subtleties and all the mark making. I’m also very interested in Palmers romanticisation of rural life which was a reaction against increased industrialisation, although his idealised rural workers were very likely living in hard, impoverished conditions. However, its hard not to look upon Palmers valleys of lush corn without nostalgia, when you are aware of the degradations of modern industrial farming in much of southern England. I suppose the interplay between pastoral, arcadian imagery and a toxic, slightly rotten surface is one of the main concerns of my work. As a painting is built up in layers of varnish and paint, the varnish will wrinkle and contract into various patterns and textures which can work with or often against the imagery underneath. I often think of the painting as having a skin that blisters and is scarred, sometimes you can squeeze out pockets of undried varnish like a nasty spot in the surface of the work.

CBP: I was once criticized in group painting show for using acrylics, ‘they are so unnatural’ I couldn’t say anything, but another artist leapt to my defense and asked the other artist ‘what is natural?’ Could you talk about what natural or nature means to you in relationship the landscape you work from and in and the nature of the paint and materials you use in your work?

SD: I’ve been living on a hill farm in Northumberland for a few years now after having done a residency nearby at VARC (visual artists in rural communities) so have become quite focused on the surrounding moorland landscape for my work. What initially seems a very natural landscape with its sheep farming that has been a constant in the area for generations, was a hundred or so years ago quite an industrial place with many mines, quarries, limekilns, railway lines etc, that are now visible as subtle, grown over features in the landscape. The nearby Kielder forest is a massive monoculture of Spruce trees packed so tightly in rows that you cannot walk into it, buried within this like ghostly remnants are dry stone walls and sheep folds from the last century. So it seems the ‘natural’ landscape is one of continuous flux, although often shifting in ways that are imperceptible to our daily lives. I try and reference these thresholds between nature and artificiality through the use of picturesque motifs that are undermined on closer inspection by the artificiality of the materials. A beautiful sunset can become slightly polluted or the air in the painting may seem to be congealing or carrying strange particles. This works best when it happens slightly by accident- overcooking the painting, messing it up, losing patience etc, if I set out to create a certain strange atmosphere it often doesn’t work.

CBP: Your paintings are technically accomplished; they appear to use technical processes and a knowledge of how mediums behave with controlled experimentation. Could you reveal something of your techniques and experimental processes?

SD: I’m actually quite sloppy with my techniques and its the mistakes that seem to lead to interesting things. For example I started using resin a few years back as I was always interested in the depth and gloss other artists achieved with it. However I never seem to be able to get the perfectly smooth surface, it always seems to form irregularities- bubbles, separating out etc, but I actually like these random elements as well as the bits of dust that get in. Its good to have something to work against and to build up an interesting surface that interrupts the image somewhat. My current thing is using metallic paints which alongside the often highly reflective surface, makes viewing the painting quite an active experience and really difficult to photograph.

CBP: What is your current studio routine and what projects are you working towards at the moment?

I’ve a small home studio where I’m painting a lot in the evenings at the moment, it gets dark so early up here so I make sure I’m out for a cycle most days which feeds into the work as well as helps the mental equilibrium. I’ve been working towards a group exhibition that is the summation of a 2 year project at VARC called Entwined, involving various artists responding to different aspects of place. The project has been supported by Northumberland Wildlife trust, Newcastle, Northumbria and Sunderland Universities as well as Northumberland national park amongst others and the final exhibition and publication launch opens at the Assembly house in Newcastle on the 1st December.

Standing stone with cup and ring marks, 16cm x 11cm, oil on board, 2018

The woods at highgreen, oil and resin on board, 25cm x 19cm, 2020

Sam Douglas lives and works in Northumberland. Recent exhibitions include; 2021 The John Moors Painting Prize, Walker Art Gallery and 2020 Field work, solo exhibition at The Eye Sees, Arles, France.

Entwined: Sam Douglas – Ancient Landscape and Mystic Visions – YouTube