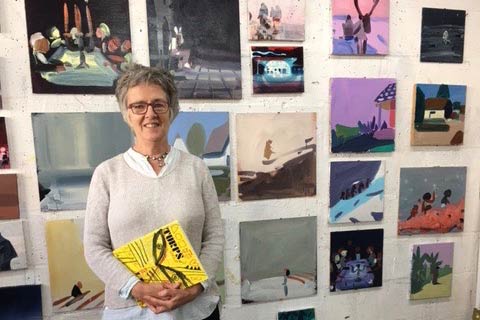

Susan Absolon: Artist of the Month

Artist of the Month September 2022:

Susan Absolon, selected and interviewed by Paul Newman for CBP.

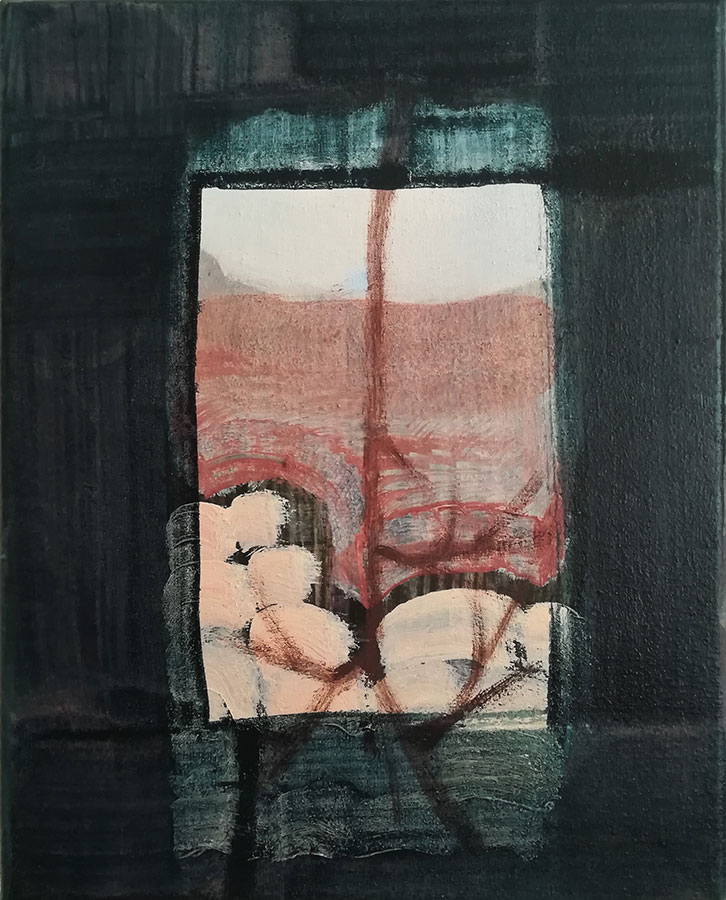

The motifs in Susan Absolon’s paintings are hard to pin down. They avoid declaring their origin or context, and sit somewhere on the path between the figurative and the abstract. A love for the material qualities of paint and working with colour, and a fascination with semantics and the slippery interplay between visual and verbal language, guide her working process. Different types of picture are allowed to emerge, sometimes in series that evolve over a long period of time…

CBP: You won the Contemporary British Painting Prize in 2021 and this year’s exhibition is about to open. How has it been for you and your practice since being announced the winner? Have there been there any changes or developments in your painting?

SA: It’s still a surprise to me that I was awarded the CBP Prize. I mean, who’s to say? There’s a lot of interesting work being made. It was unfamiliar to have a spotlight on my work, to see it shared across social media, and to reach a wider audience. But with any success there’s a fleeting sense of achievement. You’re buoyed momentarily, then you’re back in the studio trying to fix unworkable paintings!

Something I’ve really valued as last year’s prize winner is the opportunity to be a selector for this year’s prize exhibition. It’s added a dimension to my perspective as an artist. It was demanding and intense work, a big responsibility, but very gratifying to advocate for the qualities of other painters.

Where my own work is concerned, material, process and day-to-day circumstances influence the paintings I make. I don’t take an idea to a painting at the beginning, so I’m always dealing with change, looking for something different from one painting to the next. I used to think I was undisciplined, restive, as if I should have thoughts about subject or what I might want to see. It’s uncomfortable not having any clarity at the outset, but it’s how I need to work. There are many unresolved paintings around me all the time, possible directions that could be followed in a variety of ways. I resist consciously making bodies of work, though related works seem to appear over an extended timeframe of months or years. So there’s an ebb and flow, a constant questioning of what I want to see; a dialogue between me and paint rather than a plan to develop this or that.

CBP: Can we start at the end. Your paintings reveal something of the journey they’ve been on. They feel resolved and have settled, have an ethereal nature, with the potential for further shapeshifting. When do you know a painting is finished, is it the same gut feeling for each one?

SA: Generating a painting and moving it along is mostly a random process shaped by the colours I mix on a given day, the viscosity of the paint, the physical means of putting it down, and the way it’s taken by the particular support. I like to resist external references for as long as possible. In my head ideas might be forming, they come and go, but I delay committing to a specific direction. A painting can change character entirely from one working to the next. That’s perhaps how the ‘shape shifting’ comes about. There’s a lot of trial and error, ghosting, an evolution of the pictorial space, and modification of gestures from their initial scripting. There can be hints of what might have been, or what might yet crystallise.

Each painting has its own timescale and its own trajectory. Allowing my left-brain to direct a painting seems to stifle it. That said, I love language, analytics, information and reasoning, all left-brain functions. But these doesn’t seem to help me develop a painting. It’s such a relief when I let my painting brain, take over! It takes time and there are a lot of unsatisfactory stopping off points, but when I trust in the process and embrace the risks involved in an unknown direction, I know the painting will benefit – eventually.

I’m almost always taken by surprise when a painting gets finished. It’s marked by a point of recognition when the image and its title are a perfect fit. The feeling is like a key turning smoothly in a lock.

CBP: You pointed me towards Merlin James whose idiosyncratic and materially experimental paintings struck a chord when I saw them at ‘Mixing it Up; Painting Today’ at the Hayward earlier this year. He talks about time scale in his work and exhibiting older works with new. Could you talk about time scale in the making of your work, and do you ever take a finished and exhibited painting back into the studio to rework?

SA: Time runs on a different clock in art, I think. The ‘when’ and ‘how long’ questions (how long it took to make a particular painting, how many hours you spend in the studio, when you painted a particular work), it’s a metric that bundles time up in neat packages designed for other activities, mostly commercial or administrative, and it’s not useful for art.

Some paintings emerge quickly. Mostly, I labour, set aside and return many times. Unfinished paintings lie around for ages, and that’s fine. I can’t concentrate on only one painting until it’s finished. I also can’t seem to make serial paintings consecutively. There are connections between individual paintings over extended periods of time. So the time embedded in a painting is both immediate and stretchy. It’s not a given that artists produce work that’s incrementally more interesting over time, so it makes sense not to place too much value on the date when a particular work was made. Older work can wither in the storage rack without opportunity though. I think there’s a case for a more flexible approach for artists to exhibit older work. The right context for a particular work isn’t always there immediately. Open calls tend to time-bar work made before a specified date; it’s not helpful.

I’ve certainly reworked paintings I’d thought were finished. I don’t think I’ve reworked an exhibited painting, although I would if I wanted to. I recently finished a painting I’d been trying to sort out for around 10 years. I could have thought of it as finished a number of times over the years, but it’s never right to settle for ‘it’ll do’.

Another aspect of time, is the length of time I keep a painting to myself after it’s finished. It would be easy to succumb to the pressure to feed the beast of social media, but it can become a millstone. I like to hold off, to keep something back, to wait for the right context.

CBP: He also talks about the scale of his paintings; often producing small scale painting as you do. Can you discuss the notion of scale in your work in terms of your experience of painting and the paintings as objects for the viewer’s engagement with them?

SA: I enjoy the discipline of making a small painting and I’m often drawn to the smaller works of other artists. There’s nowhere to hide either as a painter or a viewer, you have to engage with it whole. I don’t like feeling overwhelmed by the scale of huge paintings; I’m looking for a relationship with a painting that encourages a sort of privacy, the close encounter that a small work demands.

The largest paintings that I make are around 140 x 130 cm. Anything larger is difficult to move into and out of my studio. Also, I don’t have the physical strength any more to handle large paintings, to construct and stretch them (which I prefer to do myself), to move them around, and I’m running out of space to store them. Making large paintings flexes a different muscle but I enjoy the quiet anarchy of putting something small into the world, a counterpoint to wall-swallowing paintings, and decadent consumption of materials. The Danish potter Anne Mette Hjortshøj speaks of ‘paying honest attention’ to the work you make, to respect its nature and scale, its construction and materials. The message is a sound one whatever your medium.

CBP: What are your starting points? Do you work from drawings and source images or go straight to the canvas, relying on a developed instinct, perhaps reacting to other paintings in progress or completed?

SA: In his essay on my work in the 2021 CBP Prize catalogue, Matthew Burrows asked about drawing and I said that it’s not part of my practice. On reflection, that’s not accurate. Whereas I don’t draw as a habit, or as a form of note-taking, rehearsal or preparation for painting, or directly from objects, photographs, people or landscapes, I drop in and out of a certain kind of activity that doesn’t involve paint. This happens as an urge to use, say, a soft pencil, charcoal, Indian ink, or to work blind, for example through carbon paper. I don’t think of it as drawing though, but rather a different approach to making visual connections through material.

Drawing also happens in a painting, with paint, though I don’t use source images for that. There’s nothing more thrilling than responding purely to material and process as a way of finding something new, moving a painting on and trying to sort it out.

You mention reacting to other paintings, working in a relational manner. A lot of my work sits within a number of loosely related series. But a series evolves over time rather than in a consecutive or finite way. When a painting is resolved, it seems like it’s the only one of its kind that will be needed. But over a period of weeks, months or years, there’s a restlessness that makes me revisit some aspect of a painting that had appeared to be hermetic and complete. The link between works can be a quiet thing and sometimes only obvious to me.

Source material is something that I draw upon late in my process and it isn’t image-based. There is a process of osmosis from daily life, activities like reading or writing poetry, having a chat with a friend, documentary material, or going down the Google rabbit hole (my search history would make bizarre reading). The starting point for a painting that I’ve mentioned previously means that each new start really is a blank canvas. Images from life can be extraordinary and I love that visual nourishment, but using an image as a starting point doesn’t work for me.

CBP: Describe something about your mark making processes in terms of applying paint and scraping back and the different speeds you paint at.

SA: Even on a small scale, I’m quite a physical painter. Mostly I paint quickly and in short sessions at different times of day, whatever size I’m working on. I use a variety of implements and techniques to apply or remove paint so that the result isn’t too predictable. I try not to overthink it, to get tight too quickly.

CBP: Can you talk about the figuration in your work? There are sometimes singular forms, sometimes repeated gestures, or elements of both like in ‘Persian Blind’.

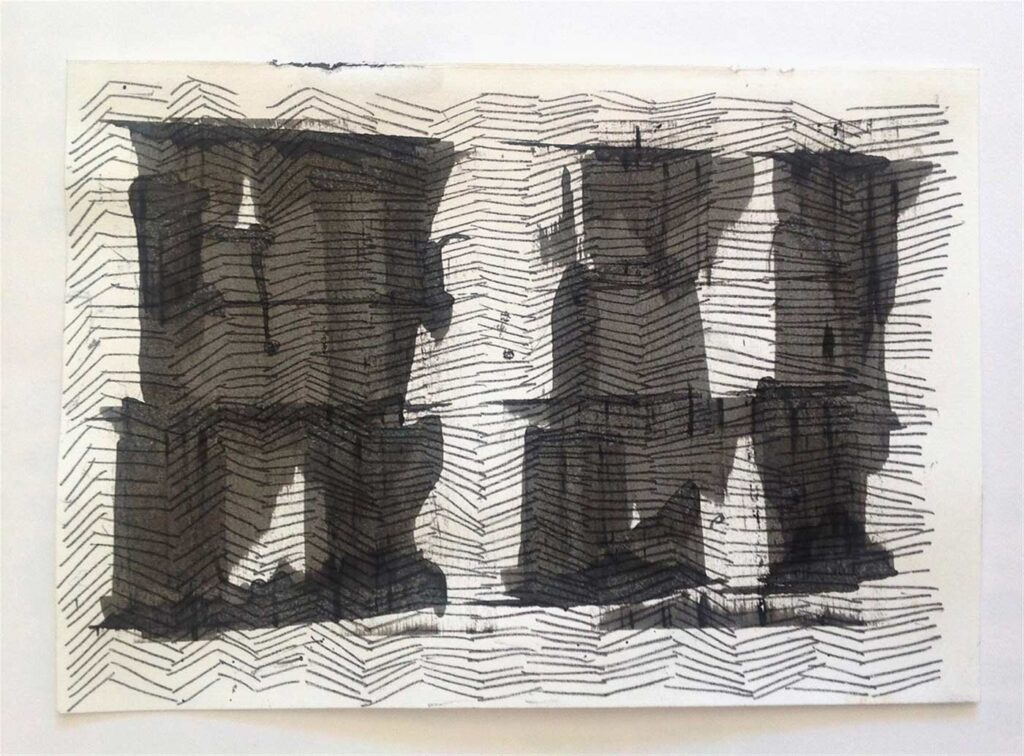

SA: I’m not comfortable with figuration. The risk in naming a motif or form in a title is that it can encourage a surface approach to viewing the work. Titles offer potential to either reinforce or undermine certainty of the visual form. A gesture or form that’s repeated manually has inevitable flaws and introduces instability, acting like a Chinese whisper, a stutter, or a mutation, and that’s really useful. The direction of a painting I’m working on is often found when my internal monologue is paused by a narrative (personal or otherwise) that connects unexpectedly with the material process. The early history of the Venetian blind is not entirely certain, but it’s thought to have originated in Persia, not Venice. ‘Persian Blind’ may or may not be interesting as a motif, but the motif isn’t the point of the work. The title gave me a reason and a context for running with an idea visually. The repeated gesture of the horizontal line is a reference to the structure of a Persian blind – an efficient window covering that relies on alignment and coordination. The visual slippage in the painting undermines the motif’s ability to function. What does this amount to? That’s where I think painting (art more generally) has its power. In creating a new thing at the point where an image and words associated with it coincide. It suggests a reading of the world that reflects a complex, mutable reality, rather than an anecdotal and fixed one.

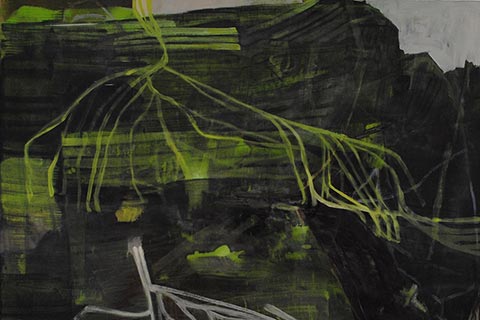

CBP: It feels like there is a narrative about relationships; how your forms relate to each other and figure / ground relationships. Also, associative relationships; how your forms potentially relate to recognised things or spaces in the world. As an example, landscape references such as the root forms in ‘Life Support’ and ‘Under Cover’, or the window composition in ‘Memory and Forgetting’.

SA: Beyond process, when a painting needs to be resolved, I approach motif or form tangentially, often by sifting ideas in a verbal process using Thesaurus or other written sources. This helps to bring an otherwise open-ended abstract painting process back into the everyday. Duplicity of meaning can create the space for doubt, suggestion, possibility and association – things that I like to work with. The existential nature of making art, and its metaphysical potential are at the heart of doing it or viewing it. The pictorial space of ‘Life Support’ might be read as a landscape, its organic forms hinting at fields, a tangle of roots, something concerned with the land sustaining life. But the title also leans towards a term commonly present in a medical emergency. Beyond either of these is the important possibility that the act of making the painting, or its contemplation by a viewer might itself be a type of life support.

‘Memory and Forgetting’ derives from a personal narrative, rooted in the everyday. But as a painterly conceit it’s a fairly useful way of dealing with imagery where I’m trying to make forms and spaces that are both precise and equivocal.

CBP: Can you talk about the relationship with language to your work, in terms of painting that can communicate something from within itself without the need for words or descriptions? Do you have any literary references that infuse your work?

SA: Thesaurus is one of my closest friends. It’s not that a painting needs words or a description, but words are the stuff of thoughts and thoughts are generated by connecting with our senses. So even when an artist avoids titles, or a curator exiles the written word to the independent space of the list, catalogue or informatic, the brain attaches words to the experience of looking. I have a keen interest in semantics, slippery, visual words. I collect words and play around with them, idioms, technical terms, acronyms, slogans, urban slang and so on.

CBP: Your titles are resonant and imply both universal and personal experiences, for example titles like ‘Anxiety’. ‘Girl Unnoticed’ feels like could it relate to a female experience or be interpreted from the viewpoint of an observer of a shadowy form merging into a veil. What element of autobiography and reference to your lived experiences is present in the work?

SA: Concerning autobiography, at an advanced stage in making a painting there is often more than one idea percolating. My inner monologue allows personal and impersonal narratives – sometimes of a social or political nature – to overlap. One subject leads to another, disparate ideas modify each other, make unexpected connections. Autobiography isn’t too interesting; on its own it’s a cul-de-sac, I think. A painting has to earn its place by pointing to something beyond the personal, become a form of connective tissue, offering the possibility of a different perspective on a shared experience.

Susan Absolon was awarded the Contemporary British Painting Prize in 2021. She is a languages graduate of University College London, has a degree in painting from WSCAD, Farnham, and took postgraduate studies at Central Saint Martins in London. Parallel careers in art collection management and freelance contemporary rug design supported her early painting practice. Awarded a Juliet Gomperts bursary in 2012, her paintings have since been widely exhibited in the UK, including; Vitalistic Fantasies, Elysium Gallery, (2022), The Wells Art Contemporary (2020/22), The London Group Open (2015/17), Royal Academy of Arts Summer Exhibition (2015/17), BEEP Painting Biennial (2016/18/20/22), ING Discerning Eye, Wells Art Contemporary, ‘Supernature’ (3 venue touring exhibition), The Royal West of England Academy Open, ‘Matthew Burrows Selects’ Unit 1 Gallery/Workshop, London, ‘A Generous Space’ Hastings Contemporary, Linden Hall Studio, Deal, SFSA Painting Open, PS Mirabel, Manchester, Angus-Hughes Gallery, ‘Painting [Now]’, Studio One Gallery.

Susan Absolon website