Susan Gunn: Artist of the Month

Artist of the Month November 2023:

Susan Gunn, selected and interviewed by Paul Newman for CBP.

“In Susan Gunn’s paintings there is a subtle tension between the golden section formalism of their geometry and the unruliness of the free-form cracking. They each balance control and abandon, deliberation and chance. This is not the frivolous feminine but the ferocious one, celebrating healing from trauma and taking up space, unapologetically…majestically. Her visceral, loaded work has the monochromatic discipline of Robert Ryman and the meticulous abstraction of Callum Innes” – Curator Cherry Smyth

Selected for the RA Summer Exhibition 2018 curated by Grayson Perry & David Mac. Photography: Peter Huggins.

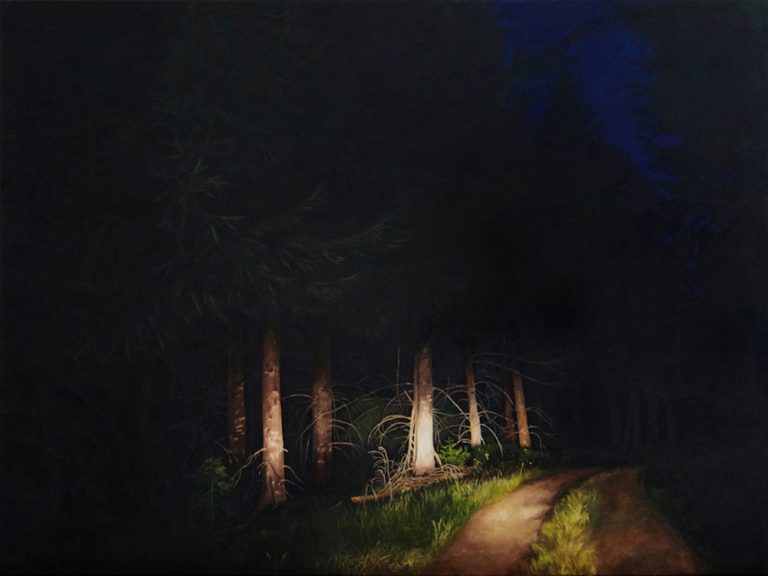

CBP: I recall seeing your painting for the first time at Darkness at Noon, an exhibition at ATP Gallery, London. Its cracked iridescent and haptic quality gave the overwhelming desire to want to touch the work. Can you talk about surface as a theme in your work?

SG: I loved responding to the concept put forward by the curator Ruth Calland for the Darkness at Noon show at APT Gallery in 2021. The gilded gesso surface reflects gloriously, a minuscule amount of light in the dark and I had great fun photographing it outdoors at night during a full moon. The idea of straining to see, and the reflection of light which resonates back to the viewer excites me as an artist. I relate to the haptic desire to touch, and its non-verbal connotations to perceive a work through the senses. Resonance evokes the Latin resonare – to echo, for a work to illicit this response from the viewer is a welcome form of engagement.

Photography: Klein Imaging.

CBP: Your paintings feel very autonomous and independent of specific narrative references. Can you discuss their object quality in relation to some of the contexts embedded within the work?

SG: I began making gesso grounds at art school around the year 2000, initially with a view to painting on them. I became quite besotted with the feel and touch, and the making of the marble, slab-like surface. I sense it has a diminutive feel of the monumental. The cold, alabaster sensation of the raw gesso that is newly dry requires a degree of energy and labour to bring the smooth quality from the rough, grainy texture by rubbing it, somewhat in a monotonous fashion. I imagine Lady Macbeth who cannot erase the spot from her hand however much she tries. I engage, in a semiotic sense, with the care and nurture of the surface, rubbing it with water and canvas remnants. I liken it to a form of ritual, like the washing and cleansing of a cold body or the polishing of a gravestone, or the shine of a soldiers boots on parade.

In The Poetics of Space, the philosopher Gaston Bachelard talks about ‘imbuing an object’ with a kind of ‘dignity’ when a consciousness to clean or care for the subject is realised. In this sense, the painting, the objet petit is a focus, the unattainable object of desire; to liven the surface is impossible, but the energy taken in the process fills a longing to bring an object to life. I once exhibited with the artist David Mach at the Bo.lee gallery in a show titled, ‘Natures Alchemy’. During the artists’ ‘in conversation’ event, he talked about the compulsion to repeat, and the absolute absurdity of making art, and this totally resonated with me. The futility of it!

Photography: Alan Ward.

CBP: One of the references that comes to mind is the Japanese art of Kintsugi and the exquisite beauty of repaired imperfection. Is this a philosophy that you draw upon?

SG: I am very drawn to the philosophy of Kintsugi. I didn’t know about the concept when I first began to create my paintings but I have since studied the fundamentals of it. I recognise the beauty of imperfection; the idea of embracing the flawed and this marries with my desire to revive and hold together the broken surfaces in my work.

366cm x 91cm x 4cm – (122cm x 91cm x 4cm) – Composed of 3 panels, 2010

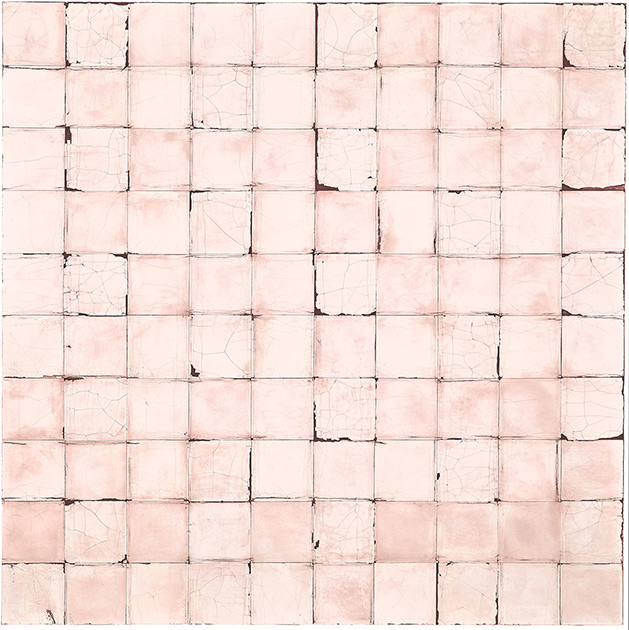

CBP: Can you talk about the gold paneled work installed at Salthouse Church as an encounter with that space?

SG: Aurum was a site-specific commission for the Bell Tower initiated by curators Yvonne & John Millwood to celebrate the 10 year anniversary of the North Norfolk Exhibition Project at Salthouse Church on the Norfolk coast.

There was a monotony, a laborious act of repetition in the painting of a series of 144 square gesso grounds across 3 canvases. The tedious nature of repeating the same process emphasised the crux of my work. It highlighted the fact that however much one repeats the same layering of the gesso over and over, the way the fissures appear in the dried gesso is different as the surfaces crack differently, each square is unique. The grid geometry echoed the crisscross lattice of the leaded windows.

In an abstract sense, my perception of the painting was of a patchwork quilt that referenced the unspoken dedication of volunteers that through time had worked behind the scenes of village life. The work was hung from the tower roof slats on fishing line, invisible to the eye. As the air circulated around the draughty church building the artwork moved with a gentle levitation which added an ephemeral quality to the installation. The art critic Ian Collins likened the work as “a perfect meditation on ancient and modern and a timeless hymn to light” which I loved!

On the evening of the summer preview, it was unusually dark and stormy and inside the church it was very dark; the gold leaf on the surface of the painting reflected the sparse light and lit up the whole building.

CBP: Your painting process appears very technically considered in terms of the medium and how it reacts and behaves, in particular your stable cracking. It’s like a kind of alchemy. Can you give some insight into your painting process and use of Gesso and other mediums?

SG: When I was learning how to make a traditional gesso ground at Art School (using gypsum or whiting and a gelatine hide glue binder) I made a number of discoveries. I was following a recipe from Ralph Mayer’s The Artists Handbook of Materials & Techniques. This was coined, the ‘artists bible’ at the time. I experimented with the proportions in the recipe and accidentally happened upon these, what I thought were exciting, cracked surfaces. In the first instance they were raw and largely unstable but I recognised a unique quality to the surfaces, it felt like I was having a conversation with the raw materials and they were speaking back to me, like, they had their own life. My tutor at the time told me I had got it wrong, gesso wasn’t meant to be cracked he said. This was during my foundation year when we were encouraged to experiment and push the boundaries to find our own voice and pathway! I consulted my ‘bible’ and sure enough, historically cracks appearing in newly made gesso are regarded as defects or flaw’s in the surface and are said by Mayer to be “entirely undesirable”. This was the beginning of a long practice of exploration. I wanted to embrace this flaw and the imperfections and accidental nuances in my work. I wanted to challenge the accepted hierarchy of thought and learn more about the natural gesso ground, its history and origins. The natural materials became the subject and the object of my work and during 2 decades of working with the substance I feel I learn more every day.

It excites me that after learning so much about how a mixture will most likely dry out that there is always a potential for surprise and failure or success. The works that I have brought back from potential failure, in that they become totally unstable, are the most satisfying pieces. The fragility of the cracked surface determines the kind of wax I use to embalm the painting. With the very vulnerable pieces I use a hot encaustic carnauba mixture that melts at a high temperature so it acts both as a wax and a kind of ‘glue’ that holds the cracks and the surface in suspension. The more robust paintings can present wax free or be imbued with a gentle beeswax.

I was nominated for the ACE escalator award by Amanda Geitner from the SCVA in 2005 and I collaborated with her again when she curated ‘An Appetite for Risk’ at The Cut 2018. She is now director of the East Anglia Art Fund at Norwich Castle. During a conversation she said to me “Susan you must be the leading expert on the gesso ground in the country”. This took me by surprise as I always thought as myself as a student of the material, always learning something about the extremities to which it can be pushed. Until that moment I hadn’t contemplated the extent of my bank of experience with it over a period of time. I was honoured to undertake an International Master Class Artist Residency at The China Academy of Art in Hangzhou, China in 2017 facilitated by the founder of Contemporary British painting, Robert Priseman where I taught post graduate students about the traditional process that dates back to the Renaissance and beyond.

for solo exhibition 2008/9.

CBP: Your paintings are monochrome, layered with subtle nuances of colour variation and the works in this article are predominantly blacks, reds and whites. Can you talk about the exploration of colour and pigments in your practice?

SG: I am interested in natural earth and mineral pigments I add the pigments to the raw binder to create coloured gesso and like any ingredients they have their own DNA as it were, a unique chemical make up and distinctive qualities as to how they conduct, dry out and present. Colour is interesting, the gesso is heated so the binder dissolves into the mixture with the pure pigment. It can dry out much lighter or darker depending on the colour. I experiment, trial and error being my go to method. I love the intensity and vibration of the strong coloured works such as the carmine and the orange paintings. The powerful strength of colour is due to the high ratio of pigment to binder. During the rubbing down stage, which I do using water and canvas off-cuts, the colour melts and goes back into the surface as the molecules disperse to add a greater intensity of hue.

CBP: There is an image of you buffing a painting with a soft brush during a gallery install, perhaps removing some debris, but is this also part of a nuanced approach to considering how light affects the surface of the painting? Can you discuss light as a virtual aspect in relation to the material elements of your painting?

SG: Ah yes, I was simply dusting the surface. The painting had travelled from the Sovereign Art Foundation, it was on loan at Norwich Castle for my solo exhibition in 2008/9. They had acquired the work in 2006 when I won the European Painting Prize.

Light is hugely important. The gesso surface responds beautifully to light as it absorbs and reflects it. Light waves resonate between the viewer and the artwork. I prefer natural light. It is really difficult to photograph my work as a technically good photograph generally does not depict the work truly. In order to take an accomplished picture, photographers typically try to omit reflection and so there is a dilemma of truth. The eye does not see like a camera lens. Making work that is difficult to photograph is a challenge, especially in the digital age. I believe that is one of the reasons why a painter paints, because there is no other way to portray the experience and phenomenology of a work.

Photography: Peter Huggins. Selected and exhibited at the Royal Academy Summer Exhibition 2018 curated by David Mach & Grayson Perry.

CBP: The image in question belongs to an intense red diptych ‘Specto Specus’. Can you talk about this work?

SG: Specto Specus was commissioned by Commissions East & Arts Council England for the ‘STAY’ London in conjunction with the Norfolk & Norwich Festival Exhibition Programme in 2015. The premise of the exhibition was to create a link between the capital and East Anglia and encourage the transport of people to Art venues around the County during the festival.

It was created to hang in the entrance space at the Great Eastern Hotel. Specto ( L > to look at, gaze, watch, observe, meditate) Specus ( L > a cave, cavern, a cavity, chasm, canal hollow cavity, chora) The Carmine pigment used to create this work originates from the serum of the female cochineal beetle, a parasite found on cacti, the colour is ancient, dating back to Aztec times. The painting embodies a vibrant red viscosity. My intention at the time was to reference the female menstrual cycle symbolic of the cycle of life and renewal; regeneration and beginning; the circularity of coming and going. The diptych was hung, separated by a zip like space between the 2 pieces. The intention was to mark the coming and going of human traffic at the hotel. The gap in the diptych echoed the opening and closing of the lifts directly adjacent to the installation in the atrium.

Wax, natural earth pigment and gesso on canvas & board support, 2005

The artwork was part of the artists nomination for the Sovereign European Painting Prize, 2006 by Cherry Smyth & Dr Colin Self where Gunn was judged to be the winner of the European Painting Prize during an exhibition at Bonhams, London.

The Judges of the Sovereign European Art Prize 2005-6: Sir Peter Blake RA (Chair of judges), Jorge Molder (Director of Gulbenkien Gallery, Lisbon), Charlotta Kotik (Brooklyn Museum of Contemporary Art & Associate of The National Gallery, Prague), Giorgio Bonomi (President of Zappettini Foundation), Jan Willem Schrofer (President of the Rijksacademie), Charles Esche (Director of the Van Abbes Museum, Eindhoven), Shaheen Mirali (Curator of the Berlin House of Culture) Ami Barak (Head of Art, Ville de Paris) Bryan Ferry (Artist & musician)

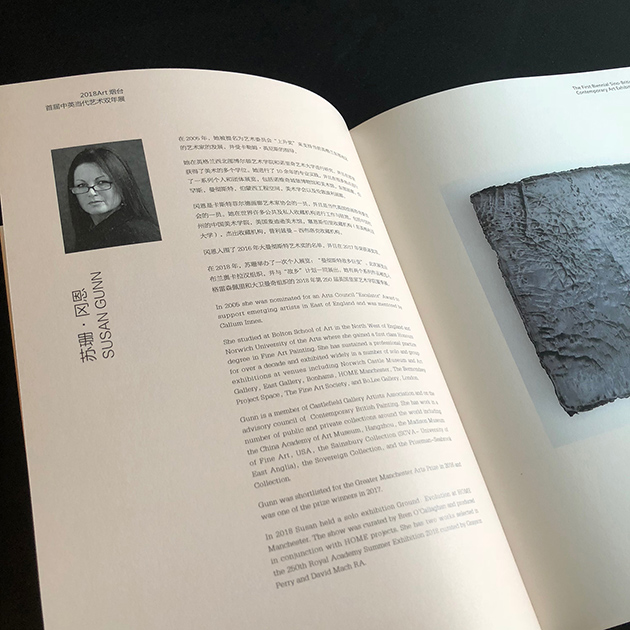

The First Sino – British Contemporary Art Exhibition, 25 September – 12 October 2018, Yantai Art.

CBP: What projects are you working towards at the moment?

SG: I am excited to be showing a new body of work at the Yare Gallery in 2024 with the Contemporary & Country curatorial team of Paul Vater and Paul Barratt based in Norfolk.

SHADOW PLAY, Yare Gallery, Great Yarmouth NR30 2RG | 15th March – 13th April 2024

Preview and exhibition events TBA

I love the paired back feel of the space. An historical Merchant House in Great Yarmouth; the old Georgian building sits on the docks, the light is incredible as it pours through great windows guarded by tall shutters of peeling paint.

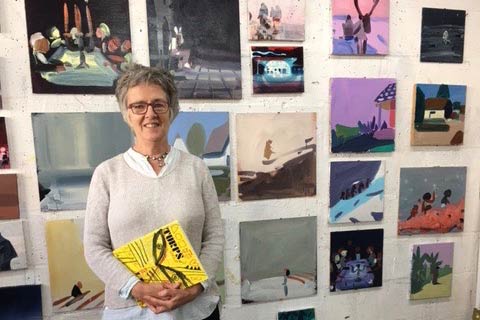

Norwich University of the Arts 170 year anniversary NUA Artist Portrait Exhibition, 2015.

Susan Gunn received international recognition when she won the Sovereign European Art Prize and is a notable alumni of Norwich University of the Arts. She is based in Greater Manchester.

Gunn has exhibited nationally and internationally in a number of solo and group exhibitions at venues including Norwich Castle Museum and Art Gallery, the Royal Academy, Pulse Miami, The National Museum in Gdańsk, and the Yale Centre for British Art.

Her work is held in a number of public and private collections around the world including the China Academy of Art Museum, the Madison Museum of Fine Art, the Sainsbury Collection at the Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts, the East Anglian Art Collection held at the University of Suffolk, and the Sovereign Art Foundation, Hong Kong.