Suzanne Holtom: Artist of the Month

Artist of the Month December 2022:

Suzanne Holtom, selected and interviewed by Paul Newman for CBP.

‘There is an overriding interest in the creative tension between content and structure in my work. I do think in terms of narratives and themes to each series of paintings, but the actual process of making is also the key idea. There are as much obliterations and erasures in the development of the paintings as construction. There is a lot of improvisation and structures are tested as much as composed. The stories in Ovid’s metamorphosis are a recurrent source and sometimes just incidental moments from my memory can get reworked into narratives. Scale is important, epic themes collide with the trivial or commonplace…’

CBP: Your paintings evoke barren landscapes, bodily forms and histories of industry. They appear to nod to surrealist landscape painters like Yves Tanguy. Could you introduce some of the imagery in the work?

SH: Yes, I can see why you made connections with Tanguy and my more recent work as I am trying to re-imagine ideas of landscape, a subject which for me seems important right now. Landscapes in my paintings are invented constructions, which often enact unstable and erratic events, an instability which seems to point to the future. My motifs are gathered from a variety of sources and often include contraptions which suggest the destructive folly of human actions and subsequent consequences on the terrain. These structures and forms can be epic, graceful, comical and precarious, such as pylons, slingshots, stacks, catapults, towers and mines. Some of the imagery is influenced by where I grew up in the West Midlands, particularly Barr Beacon near Walsall, with views of pylons disappearing into the distance.

CBP: Your distinctive painting style touches on Cubism, Futurism and Abstract Expressionism with a flourish of Rococo. The more open and fluid compositions in your recent work even evoke cartoon like motifs from the illustrations of Gerald Scaff. Could you discuss how your particular style has evolved and the referencing of any particular artists and art movements?

SH: I am particularly interested in an idea of the ‘Weltlandschaft’ or creating a ‘world landscape’ the main features being a sweeping composition from a high viewpoint, often used by Breughel and Altdorfer. This particular form of landscape creates a topography in which narratives and incidents can be played out in a sort of staged, constructed world. Space and distance appear vast and time seems to unfold rhythmically back and forth as past, present and future.

Catapults, 150cm x 180cm, oil on canvas, 2022

PULLERS AND SUMPS, 150cm x 180cm, oil on canvas, 2022

Generally I use a variety of sources as research; memories, art histories, current events and animations; from Ovid’s ‘Metamorphosis’ to Looney Tunes. Wiley Cayote animations and the landscapes of Chuck Jones have been instrumental for exploring imagery and themes of hubris and folly alongside ideas of pictorial space, movement and theatricality. Scale is an important consideration too, epic themes collide with the trivial or commonplace.

Rubens has also been a continuing influence on my paintings. I think it is the Baroque that provides the sense of flourish and dynamism, which you alluded to in your question. For me, Rubens landscapes are simply magnificent and I keep coming back to two works in particular shown together recently at the Wallace collection: The Rainbow Landscape and A View of Het Steen in the Early Morning. You also mentioned Abstract Expressionism and Cubism, my interest in De Kooning and Braque continues to be important in terms of process. There is a lot of improvisation in both my drawings and paintings, structures are tested as much as composed, surfaces reworked and the imagery is often activated with intuitive, performative moves.

And finally things I remember from childhood also creep in. My painting ‘The Dangers of Electricity’ references government public information films from the 1970’s. I recall the alarming warnings of the hazards of playing around pylons, substations and the potential for collisions of electrified wire and flying kites had a lasting impression.

CBP: These paintings contain a push pull between figure ground relationships, with bodies, landmass and architecture continuously evolving in a state of flux. It feels like a slippage between personal thoughts and memories is also a driver in the production of these works. Is this a significant aspect of their creation?

SH: Bodies are implicated in the paintings in residues of activities and actions, although there are no figures actually presented. Bodies are also implied in the landscapes through swelling forms, fleshy piles, lurching arcs, wounds and scarring. The land seems in a process of change, mutating between solid and liquid. In my most recent painting, as yet untitled, the emphasis is on shifting time and space with the layering of repeating forms. The push and pull of figure and ground is accentuated with the use of canvas thread pulled from the edges, dropped and draped on the surface, coagulating like sediment through glazes, redefining territories and suggested shifting boundaries. This process also speaks to the memory for me, distance and doubtful, an unstable structure, one memory layered on top of another in a process of accretion like geological time.

CBP: Drawing feels integral to your practice from your portfolio of an automatic type of drawing which is carried through to the paintings with their linear, almost calligraphic elements. Could you talk about your approach to drawing and how it influences the painting – if the two can be separated, or whether they are one in your work?

SH: Drawing is central to my practice in the sense that drawings are made separately, before, during and after the process of painting but also within the painting itself. At a certain points in the development of larger works, I would call the movement and intention of the brush as much drawing as painting. I can feel myself switch modes when I need to a build in linear structure or seek a more diagrammatic, calligraphic element. I do have a smaller drawing space at home as well as my larger painting studio and so both activities can also be separated.

For me, drawing can be a rehearsal, for larger work, or can be more investigative research for structures and interesting arrangements; it can be direct recording of something in front of me, or hunting down motifs which I may introduce like characters in the work. Drawing can also come from a need to simplify or minimize language. I often use charcoal to stage a kind of improvisational, more intuitive drawing process to open things up to chance and in this mode I think of Deleuze’s description the diagram as a ‘catastrophe’ – a chaos that is also a germ of order or rhythm.

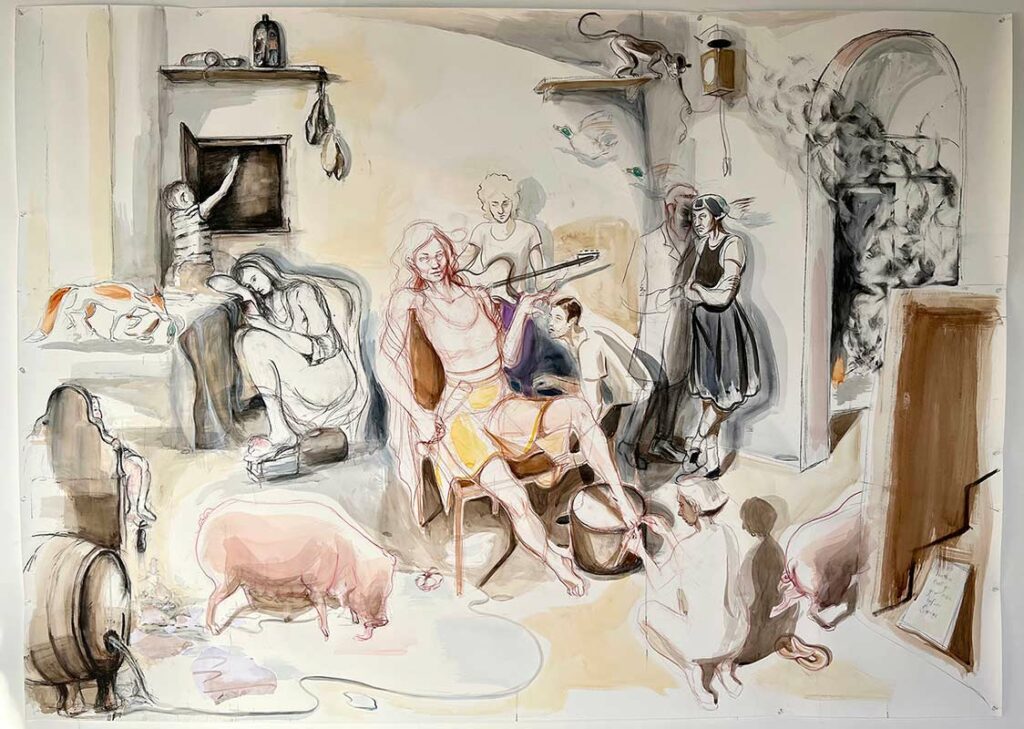

CBP: You collaborated with Lucie Eyers at ‘Eye to Pencil’ on a drawing inspired by Topsy Turvy World a 1663 Dutch painting by Jan Steen – you can see an influence on Hogarth. At first this reference looks quite removed from your own work, however there is tumultuous flow and a sense of theatre that is relatable to the sense of drama and staging in your abstract landscape painting. Did you find particular connections with your own work with this project?

SH: I have known Lucie for several years and we had talked about doing a collaborative drawing for quite a while. It seemed to me a fascinating and daunting process, and not something I had done before. We worked over a weekend at Eye to Pencil studio, first deciding on and discussing Steen’s painting (which is also called ‘Beware of Luxury’) it’s key themes and how we wanted to interpret them in a personal, meaningful way. We worked for 6 or 7 hours each day, totally absorbed. Collaborative drawing is a dynamic process, new pathways open up unexpectedly. It really is visual thinking in action; improvisation, invention and conversation – a sort of call and response process to drawing. I think you understand a lot about how you construct your visual worlds when working with someone else.

CBP: You have co curated a group show Swamp Legends at Terrace Gallery, referencing a 1919 Paul Klee painting. ‘…a visionary world where time and space unfold with a strange logic.’ Can you discuss this inspiration for the exhibition?

SH: This was a show I co-curated with Miranda Boulton. The theme came from the title of a painting I had made several years ago which focused attention on the open and sometimes uncontrolled process of painting. We each invited artists to submit work from the studio that felt a bit raw, exploratory or work that artists might not be yet sure about. We were interested in work that each artist thought was emerging or evolving into something unexpected or interesting. The swamp was a useful metaphor for process as paint seems unresolved in its identity, often suspended in a state of emergence, somewhere between wet and dry. I showed paintings that had been formed from failed paintings over many years. They just evolved in a peripheral way to main work in the studio into these characters that referenced artworks I love; ‘Infanta’ and ‘Penitent’. Karl Bielik at Terrace Gallery was in interested in the proposal and we launched the exhibition in November. Terrace is a great space for creating conversations about issues in painting, and it was a real privilege to show with this wonderful group of artists work. Several CBP painters participated.

CBP: What is the duration of the production of your paintings and your experience of reaching the end point, when the destination is complete and a painting feels finished?

SH: My paintings generally take a long time to make as there is a lot of decision making, testing and rethinking during the process. That, for me is one of the critical characteristics of being a painter, you have to go through the journey as images are hard won and end up being a complex container of hundreds of decisions which you simply cannot pre-empt. And one of the most difficult aspects is understanding when to stop. My general rule now is if I do not change it in 2 months then its probably finished. However, I have been known to break that rule.

CBP: Describe a typical day in your studio.

SH: In the morning I sit and look for a while before doing anything and I may do some reading or writing. I often look across several works for comparisons, similarities and differences and make some drawings in response to the canvas in front of me. I always have drawings up in the studio as prompts for possibilities. And I then set up my palette with an arrangement of colours; not too many but just enough for the days particular focus. I can easily get overwhelmed by colour and some limit on range is useful. It is mainly then a process of action, reflection, hesitation, correction, re-action. Moving near and far to the canvas, looking and painting, doubting and acting anyway, over many hours until I feel I can no longer be sure what move to make. Yet from experience, I now know that when I return the next day, with fresh eyes I will see and understand it more clearly.

Suzanne Holtom is an artist based in London. She studied at Cardiff, The Slade School of Fine Art and Turps Art School.

Holtom’s practice is in painting, she was included in The Jerwood Painting prize in 2003, Birth Rites, a residency and touring exhibition 2008 and has exhibited regularly in group and solo exhibitions in London and the UK. Suzanne is a member of Contemporary British Painting, her most recent solo exhibition was Fortune and Folly, Hampstead and group exhibitions; Vitalistic Fantasies, Cello Factory and Turps Painting show in 2021.

Recent Exhibitions include: 2022 This Years Model, Studio 1.1, London, A Generous Space 2, Artist Support Pledge, The New Art Gallery Walsall, Paradoxes, Contemporary British Painting, Quay Arts, Isle of Wight, Blink ‘Room Share 2’ Safehouse One, Peckham, London, Drawings from Experiences, Eye to Pencil, London.